Lessons in Love and Violence

Royal Opera House, 26th May 2018

Here is an extract from an illuminated manuscript showing Eddy II getting a crown. Or more precisely a second crown. Not sure what that is all about but given he was by reputation a high maintenance sort of fella maybe two crowns makes sense.

George Benjamin and librettist Martin Crimp had a massive hit, (by contemporary opera standards), with their previous collaboration Written on Skin, which in terms of repeat performances has gone down better than BB’s Peter Grimes. Having finally seen it at the ROH in January last year I can report that it is pretty much as good as it is cracked up to be. GB is a superb dramatic composer for drama and, specifically, for the very particular prose that MC creates. I was not entirely persuaded by the only play of MC’s that I have see, The Treatment (The Treatment at the Almeida Theatre review ***), but I think he is growing on me.

This time round they have taken seven “events” in the life of the infamous Edward II, wisely leaving out his messy end, to tell the story of his relationships with lover Gaveston, wife Isabel and rival Mortimer. The two royal kids are thrown into the somewhat unusual household and we also see associated flunkeys and down trodden hoi polloi who were suffering under Eddy’s spendthrift ways. We begin with the banishment of Mortimer, then Isabel joining the plot to murder Gaveston after seeing the desitution of the people, Gaveston predicting the King’s future and then being seized, the King disowning Isabel after Gaveston’s death, Mortimer and Isabel setting up a rival court and grooming young Eddy (to be the III), the King’s abdication at Mortimer’s behest and finally the young Edward III seizing control from his Mummy.

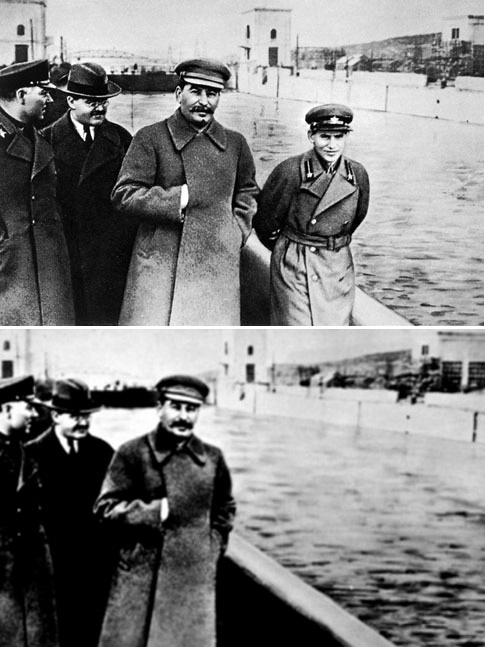

As you might surmise the focus of MC’s story here is more on the “domestic” struggle between the “couples” and less on the conflict between King and nobles. The relationship between Mortimer and Isabel and Isabel and Edward II is given as much weight as that between Gaveston and the King. This, together with the truncated plot, makes it very different from its most obvious precursor, Marlowe’s Edward II, or, more precisely, The Troublesome Reign and Lamentable Death of Edward the Second, King of England, with the Tragical Fall of Proud Mortimer. Now I happen to believe Marlowe’s play is one of the finest ever written, comparable with Shakespeare’s History Plays. But it does go on a bit. If MC and GB had attempted to set the whole story as an opera I would still be sitting there two weeks later. So Kent, Warwick, the Spensers and all the other nobles. Canterbury and the bishops, Hainault, the Welsh, the sadists and various other hangers-on are absent. As are France, fighting, Kenilworth, scythes and pokers. The key themes in Marlowe’s play, his two fingers to his own contemporary society, namely homo-eroticism, religion and social status are downplayed, Isabella’s role and the passion between the four main protagonists are foregrounded.

Extracting these key episodes and, in some cases, manipulating them to allow GB to weave his marvellous score around them, was a classy move by MC. His libretto, as in pretty much all he writes, swings from the prosaically direct to the cryptically poetic. I mean this as a compliment but his writing is not florid but quite angular with intriguing turns of phrase and clear delineations between characters. I gather that once they have agreed the shape of the work, MC goes off and writes the whole thing, with minimal consultation, before handing it over to GB, who then slowly and patiently builds up the music from the “bottom up”. At least that is what is sounded like from the interview in the programme. But given how distinctive, dark and clever MC’s approach is I can see why it works. GB knows the “voice’ he will write around and, as in their prior collaborations, he knows his musical style, which has itself been through iteration, will fit the libretto.

The music is superb. The orchestration is immensely colourful but GB only uses large scale forces occasionally. Most of the time small clusters of instruments are used to create different moods in each of the seven scenes, notably from bass clarinet, bassoons and brass. The percussion section gets to play with all sorts of new toys. A cimbalom gets an frequent airing. There are probably motifs, patterns and structures within this but you will need to find that out from someone who knows what they are talking about. All I know is that music and drama were perfectly matched across the compact 90 minutes. I think the emotional extremes were more pronounced that in Written on Skin which had a more mythic feel. GB ratcheted up key points in the action by plunging us into dramatic silences. In Scene 3 when Edward and Gaveston private tryst is interrupted by Isabel, the kids and the courtiers and in Scene 2 when the people impinge on the Court a rich musical chaos is invoked. Harmony and counterpoint are wound up into a ball before collapsing.

The production, courtesy of the genius director Katie Mitchell, regular design collaborator Vicki Mortimer, lighting from James Farncombe and movement from Joseph Alford, reflected the enclosed and intimate nature of the drama. Each scene was set in a royal bedroom, which revolved to offer a different perspective. This included the “private” entertainment in Scene 3 with Eddy II and Gaveston and the mirroring “public” entertainment in Scene 7. The “people” were given an audience before Isabel in the bedroom in Scene 2 to air their grievances. Mortimer’s household and the King’s imprisonment at Berkeley are also presented in the confined, intimate setting of the bedroom. A massive fish-tank, which drains of water and therefore life through the scenes, is both visual treat and prominent symbol. There is a Francis Bacon style painting on the wall: that probably tells you all you need to know about the uncomfortable, existential aesthetic the production seeks to traverse. There are one or two predictable Katie Mitchell cliches, slow motion soft-shoe shuffles anyone, but the tableau are undeniably effective, When you are stuck up in the Gods, (you would be hard pressed to be further away from the stage than I was, me being such a tightwad), this matters. At this distance the Court becomes a dolls house, an interesting perspective in itself, so the “choreography” that the director brings to proceedings, matters more than the close up expressiveness of the singers.

The ROH orchestra was on top form. Mind you if you have the composer himself conducting then there is little room for error. This is not a chamber opera, GB’s sound world is too rich, but some of the textures require various players to push their technique which they certainly did. I can’t really tell you much about the skil of the cast, they all amaze me, but Barbara Hannigan, as she always does, was off the scale as Isabel, vocally and as an actor. Stephane Degout bought a petulant, entitled air to Edward II, Peter Hoare’s Mortimer was a mixture of ambition and pragmaticism. Gyula Orendt stood out as Gaveston in his scenes with the King, a mystic of sorts. Samuel Boden’s sweet high-tenor stepped up very effectively towards the end as the Boy King and Ocean Barrington-Cook, (well done Mum and Dad for the name), artfully portrayed the damage done to her and her brother by having to witness the turmoil, despite not having a voiced part (another clever idea from the creators). The children were, I suppose, the ultimate recipients of the “lessons in love and violence” that we the audience were also privy to. Though the production was smartly modern-dress there was no crass attempt to draw any lessons for our own times but the plot, MC’s libretto and GB’s music combined to underscore the tension between the private and the political for those that wield power across history.

My guess is that if I saw and heard this again, perhaps from a more advantaged position, it would merit 5*. A few punters trotted out at various junctures which intrigued me. This surely is as digestible as contemporary. “modernist” opera gets. The historical subject is not obscure, the plot direct, music is beautiful, the libretto intriguing, the staging is excellent and it is hard to imagine the performances being topped. (the vocal parts were largely written for exactly this cast). Not much in the way of tunes and no arias, but surely the most cursory of examination would have revealed this in advance. The dissonance is never uncomfortable and is rooted in chordal progression. And it is short so why not see it through.

I would assume that GB and MC will, in the fullness of time, have another crack at this opera lark given how good they are it but I wonder if they have exhausted for now the “Medieval”. Like Written on Skin there is something of the illuminated manuscript here, (see what I have done there), a jewel like morality tale, (without all the God stuff). Suits me but with this amount of goodwill, (this is a seven way co-production), surely they could get away with something genuinely of the moment next time.