Imperium I Conspirator and Imperium II Dictator

Gielgud Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, 18th July and 25th August 2018

I don’t read much. Don’t have the patience or the imagination. Much easier to get my kicks from the theatre, or from film, where other people can do all the hard work. Also suspect years of reading, writing and talking, to no great effect, in an office, for the greater good of neo-liberal capitalism, has shredded what grey matter I once had. Not like the SO. A voracious reader.

All of which means I have no view on the novelist Robert Harris. Never read anything he has written. Always had him down as a writer of pot-boiling political thrillers. Not even seen any of the film adaptions. On the strength of this majestic entertainment, an adaption of Mr Harris’s trilogy of novels about Cicero adapted by Mike Poulton, I think I might have missed a trick. It looks like Mr Harris’s books would be right up my street and he sounds like a terribly good bloke as well.

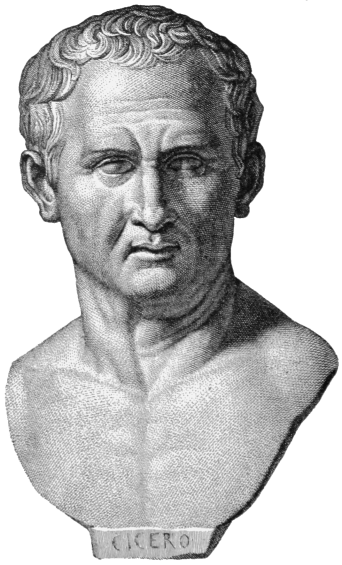

So next holiday reading now nailed down what about this RSC blockbuster? Apparently Mike Poulton had to be fairly judicious with what he took from the book, focussing on certain episodes in the maturity of the great orator’s life, but what he has conjured up, together with RSC AD Gregory Doran, is a fantastic slice of theatre. OK so there are times, as in some of Shakespeare’s weaker sections in the history plays, where the shuffling of characters on and off the stage, and the expository repeats, become a bit cumbersome, but generally Mr Poulton and Mr Doran have, through a variety of devices, ensured that, throughout the 7 hours or so of the two plays, we know exactly who is doing what to whom and, mostly, why. We also get an insight into the mind of one of history’s greatest thinkers, (or at least one of the greatest thinkers in a Western culture still in thrall to the Classical), and some universal lessons about the nature of politics and representation, and the symbiosis of word and deed in history, or at least the history of “great men”.

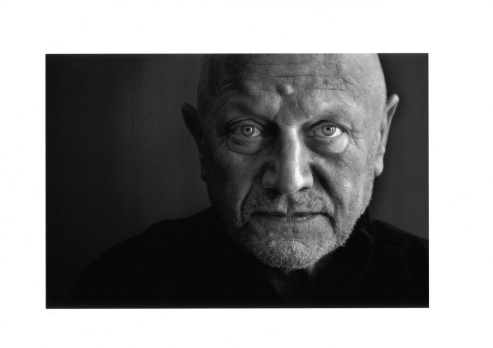

The plays also succeeds thanks to the casting of the two main protagonists. Richard McCabe is a thoroughly convincing Cicero, principled, courageous, sardonic, egocentric. Joseph Kloska as his secretary and our narrator Tiro, is equally impressive even if he has less to work with. There is more than a touch of the buddy movie about their central relationship. The audience is frequently dragged in to proceedings whether as the imagined Senate that Cicero and others address, the mob, or, breaking the wall, as conspirators in the events on stage. Not formally innovative but very satisfying in this kind of “one thing after another” history play. The political canvas, as we pass through Cicero’s election as Consul, his machinations with Catiline, Clodius, Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and, finally, Octavian (Augustus), all to protect the values of the Republic and, take note, the rule of law, is contrasted with the domestic, Cicero’s dysfunctional relationships with wife, family and proteges. If you know your Roman history and/or your Shakespeare, this is a delight. Even if you don’t the touch is so light that it is a breeze to follow.

The staging, against the steps leading up to a pair of giant. mosaic eyes, in Anthony Ward’s set, is as dramatic as it needs to be when serious stuff is playing out, but there is a thread of humour, largely milked by the two leads which prevents it turning into a slog. Sometimes the laughs, and the delivery, edges a little bit towards the Up Pompeii, but this is a good thing in my book, and much better than the alternative of ponderous epic. Composer Paul Englishby and sound designer Claire Windsor have very adroitly managed to plot a way through this tonal warp and weft, not easy to sustain over this length of time. The same is true for Mark Henderson’s lighting composition. Indeed the entire creative crew should be lauded for their studied concentration. It would be easy to let things slide, or for the pace to ease up, when you have this much to show, but, if at any point my concentration wavered, it was my fault not theirs.

With this size of undertaking, 44 named parts and more walk-ons and crowd scenes beyond that, and spanning four decades, most of the cast were doubled up across the two plays. In addition to Cicero and Tiro, Siobhan Redmond as Cicero’s put upon wife Terentia, Jade Croot as his unfortunate daughter Tullia and Paul Kemp as his bluff brother Quintus all stuck to one role, along with Peter de Jersey imperious, (no other adjective will do), Julius Caesar. When he came on all fake chummy to Cicero he captured exactly the air of a big man who knows he can’t be refused. Oliver Johnstone (after young Rufus in Part I) played Octavian with an air of even greater menace as he seized the opportunity given to him by his adoptive father Caesar Mk I. Joe Dixon seemed to relish the roles of, first, entitled aristo Catiline and then, a boozed up Mark Antony, as did Eloise Secker as the scheming Clodia and then Fulvia. This is, unfortunately, not a story with much to offer in the way of female roles, so it was a bit disconcerting, and unusual, to see so many white men on show. Still that was Rome, except that it wasn’t really.

Turning Cicero’s life, through the device of a biography written by his (originally) slave, mediated through millenia of scholarship, a writer of gripping fiction, and then on to the stage, was bound to throw up all sorts of questions about how we interpret the Ancients and how the “principles” they established still inform the world today, politics, democracy and drama, most prominently. Layer that into a fast moving biography, contemporary resonance, (for once not shoehorned in), and a history lesson, and you can see why the team here was pretty much on the case as soon as the ink had dried on the final part of Robert Harris’s trilogy, also entitled Dictator. History does not repeat itself, nor is there some deterministic arc to human progress, but two-bit, populistic tosspot geezers (always men) are ten a penny. Easy to spot, less easy to stop.

For all of you who get sniffy about the RSC and its contribution to the cultural fabric of this country, and, the world, I respectfully suggest you zip it. Here’s a great story, thrillingly told, neither too high or too low brow. Of course, as usual, by the time the Tourist gets round to seeing it and writing about it, it’s pretty much all over but I would hope this adaptation has an afterlife and I for one would love to see more “history” plays delivered in such confident, ambitious style. Like I say, if like me, you just don’t have the attention span to read a book or devote days to a box-set, then this is the thing for you. Proof positive that anyone who thinks theatre is a dreadful, long drawn out bore hasn’t tried and basically doesn’t know what they are talking about.