London Philharmonic Orchestra, Vladimir Jurowski, Leif Ove Andsnes (piano)

Royal Festival Hall, 18th April 2018

- Stravinsky – Symphony in C,

- Stravinsky – Tango arr. for orchestra

- Debussy – Fantaisie for piano and orchestra

- Shostakovich – Symphony No 6 in B minor, Op 54

I am pretty confident that no-one reads the reviews of classical music concerts posted here, not should they, since I know so very little about the music I hear, and what I do learn is ruthlessly plagiarised. But if you do stumble across this “content” by accident it really helps if you like Igor Stravinsky and Dmitry Shostakovich. A combination of my taste and that of those responsible for programming in the finest London venues means there is a lot of these two fellas on show here. More than I had realised.

This was another instalment of the Stravinsky Changing Faces festival at the South Bank, this time from the LPO under Vladimir Jurowski’s baton rather than one of their guest conductors.

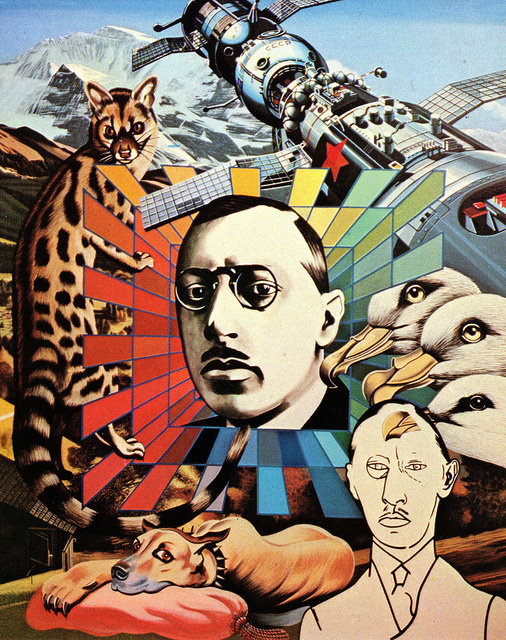

Before I get to this a shout out for the free concert in the Hall just before this from members of the LPO Foyle Future First programme. This has been created to nurture talented young musicians who aspire to a career in the orchestra. They kicked off with a bouncy rendition of Stravinsky’s “Dumbarton Oaks” Concerto, then tackled some short pieces by Elliott Carter, Luciano Berio, Edison Denisov as well as Stravinsky’s own Epitaphium, a commemoration piece for flute, clarinet and harp, which acted as the inspiration for the other pieces which, in their turn, commemorate IS. The last piece was the more substantial Furst Igor, Strawinsky by Mauricio Kagel, drawn from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor and showcasing the dramatic singing talents of young bass Timothy Edlin, and some startling percussion effects.

I chanced upon this concert. On the basis of this I will endeavour to seek out any future offerings as should you if you are in the vicinity.

On to the main event. The Symphony in C was first performed in 1940 in Chicago conducted by IS himself. The first two movements, a Haydnesque shuffle with prominent oboe, here taken briskly, and a concertante with strings sandwiched by woodwind, were written in Paris, at the same tine as IS lost his daughter, first wife and mother. No grief on show though in this effervescent neo-classicism. The last two movements were composed after IS had moved to the US and comprise a scherzo with nods to IS’s early works and a slower conclusion focussed on woodwind. The trumpet of, I think, principal Paul Berniston, also got a good workout. Like everything Stravinsky wrote, the more times you listen to it the more you are astounded by how easy it all seemed to come to him, whatever form or style he was writing in, and however “academic” the music. This IMHO is about the best Neo-classical piece ever written.

The proceeding tango for chamber orchestra was originally a piano piece, as revealed by Leif Ove Andsnes later on in his encore. Even the stuff IS churned out for money, like this, is captivating, with strings, guitar, woodwinds and more brass than you might expect. Mr Andsnes is a confident fellow, I’ve heard him play a couple of times before, and have enjoyed his interpretations of Beethoven, the Nordics and Chopin, without being utterly convinced, I regard Debussy as a bit of an occupational hazard, as it often, as here, crops up in the programmes that appeal to me. All that swirling impressionism and general diddling about doesn’t really do it for me I am afraid. The piano being the chief instrumental purveyor of the diddling about tendency for composers so inclined, I wasn’t looking forward to this.

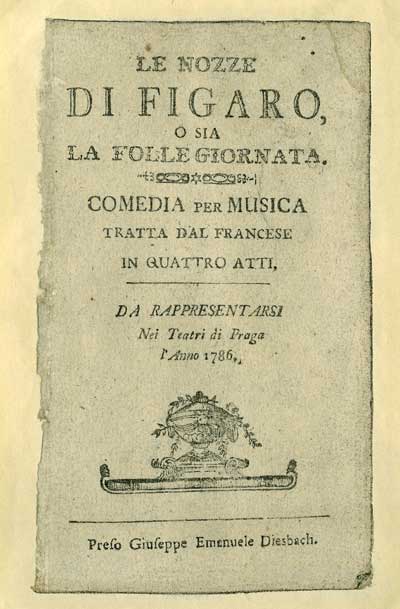

Once again my idiotic prejudices were confounded. The Fantaisie was written in 1890 as part of a prize young Claude secured but only the first movement was performed, leading CD to huffily withdraw it. Every time it was scheduled for performance thereafter, after revisions, he missed his deadlines, so that the original published score only appeared in 1919. The revisions were finally published in 1968. Leif OA has made a signature dish from this later version which is what we heard here. The first movement introduces the theme which turns up in the final allegro, there is a bit of the “exploratory” stuff which worries me but it settles into a tune by the end. The slow movement is grandly Romantic and in F sharp major. I shouldn’t like this but I did. Maybe I have a thing for this key. This moves into the the quicker, colourful finale which is underpinned by a repeated bass figure, and that, dear reader, is why I liked it. Probably because it doesn’t sound much like Debussy.

I don’t know how much rehearsal the orchestra got with the soloists. I am guessing it was limited since the programme implied we were getting the original 1919 version suggesting a bit of miscommunication. It didn’t matter. The more I hear the LPO with VJ at the helm the more I admire their unruffled ability to support, but never, overwhelm the soloist.

There is nothing diddly about Shostakovich’s 6th. After getting back in the Politburo’s good books with the 5th he went and upset the apple cart again with this bizarrely “unbalanced” though not “formalistic” symphony. 18 minutes or so of B minor largo slow movement with one of those never ending intros followed by a funeral march second theme, which is then repeated, but in a very subdued, passive way with solo flute from Juliette Bausor, ending with the briefest of recapitulation of the first themes. Then a scherzo, with trio accent, and strident climax, straight out of the DSCH copybook and a closing rondo, with contrasting waltz, that only needs a few clowns to gallop on stage to be complete and even has the enigmatic William Tell Overture which punctuates his last Symphony No 15. No fourth movement, all done in half an hour, audience always a bit taken aback, then relieved that it’s all over. And that’s the contingent, here thankfully large, who love this stuff. The best parties don’t go on too long. Who knows what it all means.

There is a lot of opportunity for pianissimo in the first movement, with most of the orchestra resting most of the time, and VJ and the LPO were keen to show what they could do. The extended second theme of the Largo was as close to eerie Shostakovichian, chair-pinning, perfection as you could ever want to hear, and the closing presto faultless. Bish, bosh. It might still be on I Player if you’re interested.