Right then. I know what you are thinking. Doesn’t this numpty know that it’s June 2017. Bit pointless talking about theatre from last year then. Well yes, you may well have a point. However this blog only started in March 2017 and it’s mine anyway so I can do what I like. And the idea primarily is to help identify some lessons about good stuff to come in future, whether it be from writer, director, cast, other creatives or venue. Anyway I suspect all you theatre obsessives will know where I am coming from anyway.

1. Hangmen – Wyndham’s Theatre/Royal Court Theatre

So i know that technically this was from 2015. But we didn’t get to see it until the transfer to the Wyndham’s Theatre having missed the Royal Court run because I am an idiot who failed to book it in time.

It is an extraordinary work. There is no-one who writes for the stage (or film) like Martin McDonagh, though there are echoes to me of the likes of Pinter and Tarantino. It is the combination of fierce intelligence, violence, humour and atmosphere. If you don’t know the plays then you may know his films, notably In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths.

So if this, or the Pillowman, A Behanding in Spokane or any of the five Galway plays from the 1990s, are revived we should pay attention depending on who takes it on. If he makes another film we should also pay attention.

If we are in New York at the beginning of next year then we should see this production of Hangmen at the Linda Gross Theater. Please just go.

We should see what Matthew Dunster, the director, can do with his adaptation of Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities at the Open Air Theatre this summer (his involvement with the Globe has been mixed – I can’t really comment as the Globe is off limits for me as it is too uncomfortable – sorry).

If and when Johnny Flynn stops singing and acting in mini-series (he is in that Einstein thing apparently – you know it is everywhere on the tube), and takes on another stage role we should go – he is mesmeric – and appears only to do top-notch theatre, Propellor Shakespeares, Richard Bean’s The Heretic, Butterworth’s Jerusalem and Rylance’s Globe Twelfth Night (though I didn’t get on with this).

And best of all we should be salivating at the prospect of David Morrissey taking on the role of Mark Antony at the new Bridge Theatre alongside Ben Wishaw, Michelle Fairley and David Calder. With Nick Hytner directing. We had a few magnificent productions of Julius Caesar recently but this has the potential to match them.

Oh and finally if there is one theatre where you should just buy “blind” if you have any interest at all in the subject based on the admittedly thin blurbs they provide just book it. Pick of the current bunch for me of the current season is Anatomy of a Suicide.

2. Yerma – Young Vic Theatre

So if you have any interest in London theatre you are probably all over this. BUT if you haven’t seen it (the performances later this year sold out sharpish) or if you don’t think this serious theatre caper is for you, then I highly recommend you watch it at the cinema through the NT Live thingamabob on 31st August.

There is much to like here. Lorca’s original play, Simon Stone’s radical re-write and direction, Lizzie Clachan’s stark but effective staging, the performances of Maureen Beattie, John MacMillan, Charlotte Randle, Thalissa Teixeira and, especially, Brendan Cowell. But in the end it is all about Billie Piper. You will be hard pressed to ever see a more emotionally involving performance at the theatre. No holding back at all.

My guess is we will have to wait a couple of years before Ms Piper returns to the stage but whatever she does after this and The Effect is likely to be mandatory (I didn’t get through Great Britain, Richard Bean’s satire at the NT though I had a good excuse).

And if we want to see Mr Stone’s magic elsewhere then we need to follow Toneelgroep Amsterdam where he has productions of Medea and an Ibsen mash-up. Will be interesting to see whether either comes to London at any point.

As for the Young Vic well right now the Life of Galileo by Brecht is playing with, drum roll please, Brendan Cowell, in the lead. Tickets still available and I loved it.

3. Uncle Vanya – Almeida Theatre

This seemed to sneak under the wire a bit. I thought it was outstanding. Maybe director Robert Icke’s Red Barn at the National Theatre or his version of Schiller’s Mary Stuart with Lia Williams and Juliet Stevenson garnered more attention, or perhaps everyone was taking a breather after Mr Icke had smashed it out of the park with his Oresteia for the Almeida in 2015. Any way up he is the most exciting director right now in the UK and this cemented that reputation.

Mr Icke himself updated the text and shifted the “action” to rural England. The production took its time and the sense of ennui was attenuated by Hildegard Bechtler’s slowly revolving set. And Paul Rhys as Vanya/John could hardy be bettered with his man-child lost demeanour. The rest of the cast, notably Jessica Brown Findlay, Vanessa Kirby, Hilton McCrae and Tobias Menzies, collectively kept their ends up. The detail of the characterisations was riveting. The individual pyscho-dramas perhaps can more to the fore pushing the social context back a bit but I reckon you can have a bit too much of the “everything’s about to go tits up in Russia and these minor aristos don’t know it” benefit of hindsight in Chekhov anyway. It is always better when you you get more of sarky Anton nailing the “shit just happens” frustrations of life.

So if you are one of the infinitesimally tiny number of regular readers of this blog you will know that I have high hopes for the next couple of productions at the Almeida: Ink by James Graham (writer of This House which may yet turn out to be an instruction manual for the vicissitudes of minority government in the UK) directed by Rupert Goold with Bertie Carvel and Richard Doyle and then Against by Christopher Shinn and directed by Ian Rickson with Ben Wishaw in the lead.

Meanwhile one of Robert Icke’s next projects is an Oedipus with Toneelgroep Amsterdam and with Hans Kesting in the lead. I pray this come to London as Hans Kesting without question is the best stage actor I have seen. OMG.

4. Kings of War – Barbican Theatre

Talking of Hans Kesting here is a picture of him as Richard III in the Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s production of Kings of War at the Barbican. TA premiered this production in 2015 and brought in to London last year. It takes five Shakespeare history plays, Henry V, Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and 3 and Richard III, and mashes them up to extract the best bits in a four and a half hour spectacle that gets to the heart of what political power means.

Is it better than the similarly envisioned Roman Tragedies? (review here – Roman Tragedies at the Barbican review *****). I couldn’t tell you. There are both works of astonishing theatre. There have been a few let downs from TA and its inspirational artistic director Ivo van Hove, notably Obsession, but this showcases what he and his ensemble is capable of. So, as and when, this returns do not miss it.

And Mr van Hove has a number of forthcoming engagements on the London stage with Network coming up later in the year at the National the pick of the bunch.

5. Escaped Alone – Royal Court Theatre

I have something of a weakness for unsubstantiated hyperbole. But here goes. Caryl Churchill is the greatest British playwright since Shakespeare. The best theatre plays with ideas and form and creates lasting impressions in the mind which simply cannot be replicated by any other artistic medium. Caryl Churchill does this again and again and again. No hype, no endless interviews explaining what she is doing/has done. Just perfectly formed, intense works that magically appear and seem to have addressed everything worth addressing over the past five decades or so. I just wish I had seen more of them.

Escaped Alone, in under an hour, explored the nightmare of apocalyptic, ecological collapse in a hilariously surrealist way, intertwined with, at turns, the banal and sinister fears and stories of four mature women ostensibly chatting in a back garden. That is my attempt at a summary but it does no justice at all to the ideas and images that just pour out of this play. As always with Caryl Churchill you just marvel at the alchemy of how so much insight into the big questions of humanity flows from these non-naturalistic, but never truly absurd, structures.

So as and when the next new play appears just go. And the same advice applies to any Churchill revival, anywhere. anytime.

6. Oil – Almeida Theatre

Back to the Almeida for Ella Hickson’s ambitious play Oil, directed by Carrie Cracknell and with the magnificent Anne-Marie Duff in the lead. So I get that the text and the pacing of the production was a little uneven but I didn’t care. Ms Hickson created such a compelling narrative, mixing the geo-political epic with a detailed mother-daughter relationship which hits you on some many levels. I have seen Anne-Marie Duff steal the show in a number of very different plays but she has never been better than in this role. And I doubt there is a better director in Britain today of towering female roles than Ms Cracknell (The Deep Blue Sea, A Doll’s House and Medea are recent examples).

Now it looks like Anne-Marie Duff’s latest outing at the National Theatre, Common, is getting a bit of a pasting. I will be taking a peek shortly so will make up my own mind. She is also pencilled in to a Macbeth next year alongside Rory Kinnear and directed by Rufus Norris. Surely that will be unmissable.

As for Ella Hickson, I would love to see a revival of Boys, and I think that it is only a matter of time before she pens an undisputed contemporary classic. And if anyone knows what Carrie Cracknell is tackling next I would love to know.

We are blessed in this country right now with a generation of outstanding female playwrights and directors but I for one would like to see way more come through. This play shows why.

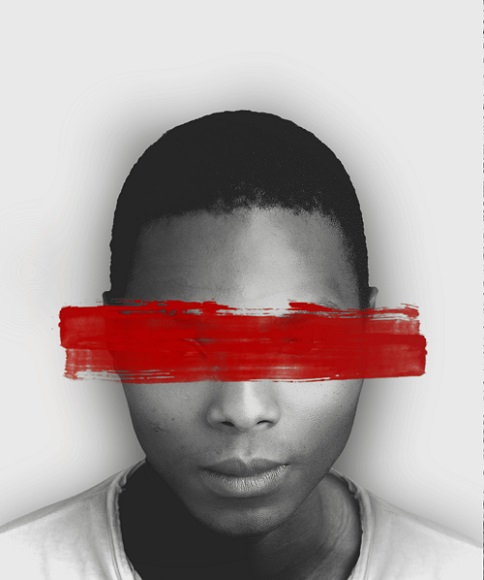

7. The Rolling Stone – Orange Tree Theatre

Royal Court, Almeida and Young Vic all unsurprisingly represented in my top ten list and I have no doubt they will be again this year. As will, I suspect, the Orange Tree which continues to turn out work of the highest quality, whether revivals or new plays. They may not always be my cup of tea but artistic director Paul Miller and his team seem to have an extraordinary knack of identifying and staging rich theatrical material.

The Rolling Stone by Chris Urch was a winner of the biennial Bruntwood Prize winner in 2013 and premiered at the Royal Exchange Manchester so was hardly a secret. But it was still terrific to see the Orange Tree pick it up for its London premiere and it deservedly won a slew of Offies (the London fringe theatre awards).

It is an examination of the persecution that gay men face in Uganda largely told through the words and actions of one family. It packs an extraordinarily powerful emotional punch and will leave you seething with anger at the actions of church, state and media which combine to pursue a modern witch-hunt.

This is Chris Urch’s second play and I await with interest his next project which I believe is a screenplay for a biopic of the life of Alexander McQueen. And without exception I keep my eye out for the excellent cast, Faith Alabi, Fiston Barek, Jo Martin, Julian Moore-Cook, Faith Omole and Sule Rimi (who has popped up in a number of subsequent productions I have seen and has been uniformly excellent in these).

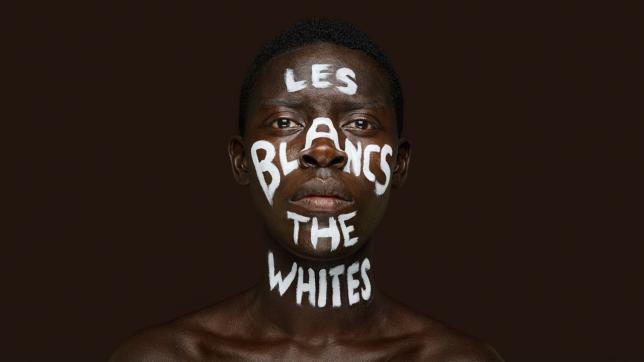

8. Les Blancs – National Theatre

The proper luvvies are in a little bit of a tizzy over Rufus Norris’s stewardship of the National. I admit it has become a bit of a lottery, particularly when it comes to the Olivier stage, but there have been some belting productions in the last couple of years. And for me this was the best of the bunch last year.

Now this probably reflects the fact that I have never seen A Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry masterpiece. Following this version of Les Blancs it is now right at the front of the queue of plays that I simply must see. I was bowled over by this version of Les Blancs. It is an immense play which explores post-colonialism in 1960s Africa with an unforgiving eye. There is a lot of grand speechifying to advance the arguments but the didacticism never proceeds to simplistic resolution. I gather Ms Hansberry’s husband, Robert Nemiroff, had a major hand in completing this play after her untimely death. The set, sound, lighting, music and even smell could not have been bettered and for once I think the best seat in the house was upstairs at the back since there was so much to savour.

South African director Yael Farber seems to have presided over a duffer with Salome currently on at the National (I haven’t seen it yet) but her direction in this Les Blancs was sublime. And I don’t know what stage Danny Sapani will next grace (you will have seen him on the telly) but wherever it is I will try to go.

9. Orca – Southwark Playhouse

This was Matt Grinter’s debut play which won the Paptango new writing prize. I thought it was brilliant. In just 75 minutes Mr Grinter conjures up a place which seems far removed from our modern world and his tale of ritual abuse in a closed community conjures up a real sense of foreboding. I suppose some might label it “folk horror” at a pinch but it was just so much smarter than that label implies. It confronts the reality of the outrages that even today are visited upon women by men who hold power over them.

The setting is a fishing community on an island to the north of Scotland I surmised. An elder sister Maggie played by Rona Morison tries to prevent her younger sister Fan (Carla Langley) from undergoing the same unspecified but clearly dreadful fate which she refused to endure. Their father (Simon Gregor) won’t step in because he cannot face continuing to be shunned by the rest of the tight knit community. The patriarchal head of the community The Father played by Aden Gillett is genuinely one of the most disturbing characters I have ever seen on stage,

I’ll stop there just in case it gets revived but this was a riveting watch under the direction of Alice Hamilton. And the set by Frankie Bradshaw in the smaller space in the Southwark Playhouse (where they put on all the good stuff) was beyond ingenious. I don’t know if I imagined the cold, damp sea air that night, or whether that was all part of the production, but I really felt I was cut off from the rest of the world and not a few yards from the Elephant and Castle.

I await Matt Grinter’s next writing excursion with extreme interest.

10. Julius Caesar – Donmar King’s Cross

This is what Shakespeare is all about. Phyllida Lloyd and her all female cast led by the redoubtable Harriet Walter added The Tempest to the previous productions of Julius Caesar and Henry IV and set them up in a temporary stage at bargain prices in Kings Cross. All three took the venerable texts and smashed them over your head. Breathtaking.

I pick Julius Caesar solely because it is my favourite of the three plays. And I think the setting of all three plays in a women’s prison achieved most resonance in this play with its themes of conflict and the misuse of power. Directorial concepts in Shakespeare are vital in my view to illuminate the timeless brilliance of the insight but they can fall flat. Not here.

I think Harriet Walter’s Brutus is the best I have seen and I would also, if pushed, single out Jade Anouka’s Mark Antony (to add to her amazing Ariel in The Tempest). She was the only decent contributor to the dreadful Jamie Lloyd Faustus and I await her next major role with interest. The same goes for Sheila Atim who next pitches up in Girl from the North Country at the Old Vic.

Harriet Walter can read the phone directory and I would still go and Phyllida Lloyd could direct a bunch of phone directories and I would still go.

Best of all this Julius Caesar will be in cinemas soon so catch it if you haven’t already seen it.

So there we go. My favourites from last year. Honourable mentions also to Complicite’s Encounter which I finally got to see at the Barbican, Schaubuhne Berlin’s The Forbidden Zone also at the Barbican, Tim Minchin’s Groundhog Day musical at the Old Vic, and Jess and Joe Forever by Zoe Cooper and Blue Heart by the mighty Caryl Churchill both at the Orange Tree.

This year is ramping up to be similarly fine for London theatre with plenty of contenders already. Enjoy.