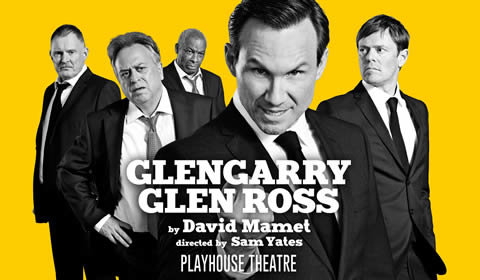

Glengarry Glen Ross

Playhouse Theatre, 25th January 2018

I am wary of West End productions that import a big American movie star to embellish a revival. And, like most ill thought out prejudice, this invariably turns out to be wrong. Still the only person harmed by this ignorance is me.

In this case though I was far more optimistic. This is, arguably, David Mamet’s finest play. A Pulitzer prize-winner no less. It was to be directed by the talented Sam Yates. The supporting cast, Robert Glenister, Kris Marshall, Daniel Ryan, Oliver Ryan, Stanley Townsend and Don Warrington was top drawer. And the Hollywood star in question was Christian Slater. Now I admit he may not be peak A list, he has been in such unutterable dross, I have never seen the West Wing, The Forgotten and Mr Robot, (I don’t have the patience for these TV series), and I can see he is a bit of a tit in real life. But when I have seen him he has munched his way through the scenery in that mini-Jack Nicholson way of his and I figured he was born to play Ricky Roma.

And so it proved. A dazzling performance. Cocksure, brash, manipulative, aggressive, dismissive but vain, hollow, deceiving himself as much as others. Ricky is about as good a character as modern drama has created but Mr Slater still delivers. The scene with Daniel Ryan’s cowed James Lingk, ably abetted by Stanley Townsend’s Shelley, was delicious, as good as I have seen on the West End stage. You could feel Ricky’s brain going through the gears so as not to lose the sale. Prodding, patting, probing, putting his arm around Lingk, not letting him get away. Superb.

Watching Stanley Townsend shift from desperation to euphoria, and then back again, as he pleaded for leads, pulled in a big sale and then realised he had been taken for a ride, was also exquisite. Kris Marshall’s portrayal of John Williamson, the office manager who eventually relishes the power he wields over the salesmen, was a revelation. Don Warrington played George Aaronow as a broken, lost figure, so easily manipulated and Robert Glenister was wonderful as Dave Moss, a man whose cunning is only matched by his belligerence.

This is as good an ensemble as you are going to see on any West End stage. Mind you I bet that is the reaction of anyone who sees it anywhere whenever it is revived. I first fell in love with GGR in, I think, 1985, the revival of Bill Bryden’s world premiere National Theatre production, staged at the Mermaid Theatre, (which is a lovely space and it is bloody criminal what has happened to it). The 2007 revival, with Jonathan Pryce and Aiden Gillen, directed by James MacDonald, near matched this. Not quite so sure about the film, what with the extra character and the softening of Jack Lemmon’s Shelley, but it should still be on your film bucket list for sure.

The salesman in the US is an iconic figure, even in a world of Amazon, internet disintermediation, telesales and the like. The skill of building a relationship with a customer or client, of identifying and fulfilling a need or want, (or manifestly not as is the case here), will always be with us. It is a potent subject for drama: the Tourist and LD remain addicted to the Apprentice, and America chose to elect an ersatz salesman as its leader. The attraction for playwrights lies in the insight the salesman offers into the human condition, particularly its uglier side, and the resonant metaphor it offers for society and economy. Hard to believe but the same subject gave us an even better play than this. In fact the greatest ever American play in the form of Death of a Salesman.

Of course the real beauty of the play is Mamet’s dialogue. And it is beautiful make no mistake. The boy Aristotle, who knew a thing or two, said drama needed heightened language, which you certainly get here, but also rhythm. a kind of music, to the interaction of the plot, characters, lines and the overall spectacle, and this is what Mamet delivers in spades. And he doesn’t hang around. Act 1, in the Chinese restaurant, is a little over half an hour here, (always fun watching the GGR virgins looking a bit nonplussed at the speed with which the interval arrives). Yet, in its three perfect scenes, we learn everything we need to know about Levene, Williamson, Moss, Aaronow, Roma and victim Lingk. In my book Roma’s soliloquy, masked as sales patter, is up there with the best ever written for the stage. And we see that pathetic combination of male aggression, false certainty and “firing from the hip” which infects modern political economy. Too often the plausible bully wins and rises to the top. And if he can’t win he throws a tantrum or cheats. It is always a he.

Chiara Stephenson’s set (and costume) design strove, as it should I think, for absolute realism, which meant a fair bit of carpentry in the interval to turn the atmospheric restaurant into the claustrophobic office where the overnight robbery barely upsets the chaos. And so on to the perfectly plotted second act. I guess the first performance I say was the best precisely because I didn’t know what was going to happen, but knowing the plot, as with all the best plays, leaves more headspace to relish the language and marvel at how Mamet captures this cocktail of virility and vulnerability without ever losing our connection with the characters. For ultimately our problem, surely, is we sort of admire Roma and we sort of pity Levene

Sam Yates as director lets the text sing and, unsurprisingly, leaves the cast to do their thing. So why not a perfect 5 stars. Well this reflects my now oft repeated aversion to West End theatres. To fund my theatrical habit means I can’t go splashing sixty quid plus, or even three figures, for the best seats in the house, willy-nilly, so I went tight here and opted for the balcony (upper circle as they term it), having stupidly ignored the advice of simian experts. View and sound commensurate with price but the seats themselves up here in the Playhouse are ridiculous. I couldn’t fit in. Not I was a bit uncomfortable. I mean I couldn’t fit in. Moving to a smaller neighbour option and shuffling around helped in Act 2 but it was still about the worst I have ever experienced. Let’s hope they never put a Hamlet on here. I know there ain’t much they can do, and that ATG has to earn its corn, but a clear indication of just how tight legroom is would be appreciated, Anyway I found out the hard way.