Ligeti in Wonderland

Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room, 11th, 12th and 13th May 2018

Pierre–Laurent Aimard (piano), Tamara Stefanovich (piano), Patricia Kopatchinskaja (violin), Marie-Luise Neunecker (horn), Daniel Ciampollini (percussion)

- Ligeti – Poeme symphonique for 100 metronomes,

- Ligeti – 3 pieces for 2 pianos (Monument, Selbstportrat, Bewegubg),

- Ligeti – Trio for horn, violin and piano

- Steve Reich – Clapping Music

- Ligeti – Etude No 8 for piano and percussion

- Conlon Nancarrrow – Piano Player studies Nos 4 & 9 arr. for 2 pianos

- PL Aimard – Improvisation for 4 hands on Poeme symphonique for 100 metronomes

- PL Aimard – Improvisation for piano and percussion on Ligeti’s Etude no 4 (Fanfares)

Shizuku Tatsuno (cello), Katherine Yoon, Yume Fujise (violins), Tipwatooo Aramwittaya, Ilaria Macedonia (harpsichords), lantian Gu, Laura Faree Rozada. Joe Howson (Pianos)

- Sonata for solo cello

- Ballad and Dance for two violins

- Continuum for solo harpsichord

- Passacaglia Ungherese for solo harpsichord

- Musica Ricercata for solo piano

Pierre–Laurent Aimard (piano)

- Etudes Books 1,2 and 3

Pierre–Laurent Aimard (piano), Patricia Kopatchinskaja (violin), Marie-Luise Neunecker (horn), Nicholas Collon (conductor), Aurora Orchestra, Jane Mitchell (creative director), Ola Szmida (animations)

- Chamber Concerto

- Piano Concerto

- Hamburgisches Konzert

- Violin Concerto

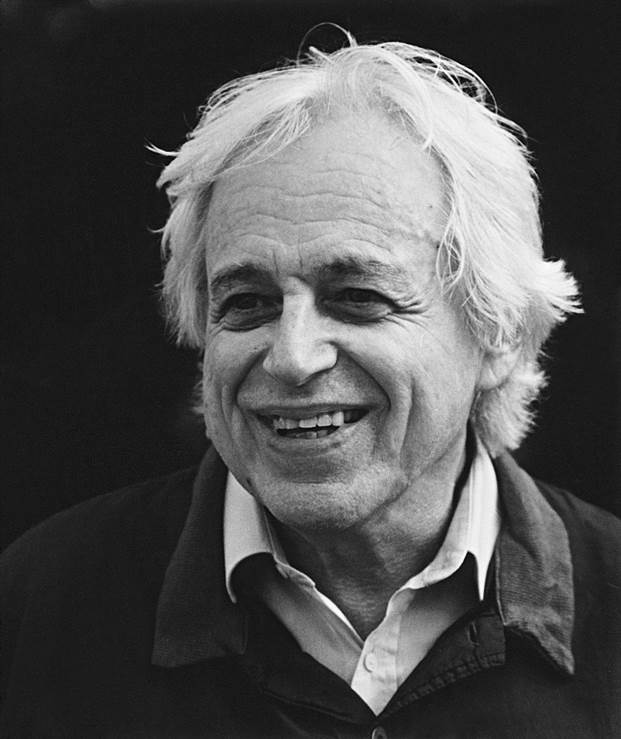

Hello. The review starts down here. As you can see the Tourist, along with many others, similarly intrigued and maybe enraptured by the music of Gyorgy Ligeti, put in a shift enjoying this weekend of music dedicated to his music.

Not one second was wasted. Some of the pieces stood out, the Trio, the piano works especially the Etudes and the Violin Concerto, but overall this was a fantastic array of performances of this brilliant composer. Wonderland for sure.

Now it takes a few decades before the new in all art forms is appreciated. Classical music, even in its most saccharine form, is not going to be for everyone. Yet it seems pretty clear to me that Ligeti, ahead of the other big name Modernists who transformed Western art music in the middle of the last century, is the one most people would choose to listen to. There is innovation and extension in his sound world for sure, there is intellect aplenty and there is memorable structure, though not the mathematical -isms of his peers, but most of all there is a depth of expression that anyone, even this muppet, can grasp. Add to this rhythm, of sorts, power, humour by the bucketload, and it’s easy to see why he gets performed a fair bit more than his contemporaries. He wasn’t sniffy about minimalism and he embraced music from other cultures. If you want to dip your toe in the modern classical world then this is definitely where to start.

There is a grand, ambitious, searching quality to his music, audible even in these smaller scale chamber and solo works. More often than not the works teeter on the brink of chaos but always, one way or another, resolve so I think it is optimistic on the whole. And, importantly, as with Luciano Berio, (another favourite for me alongside Xenakis and Penderecki), the history of art music is not smothered or ignored.

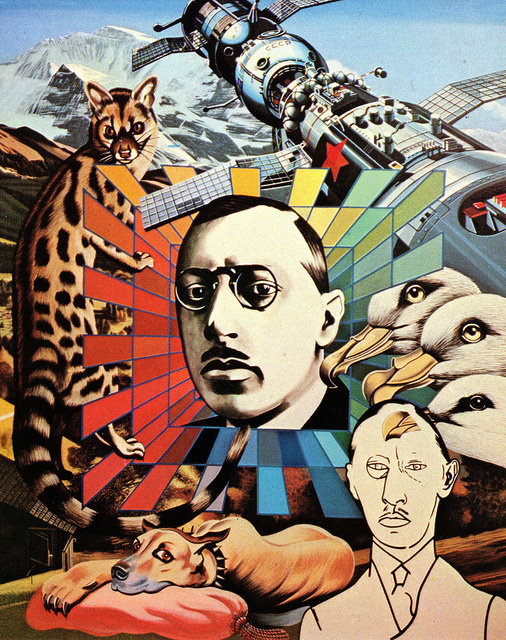

Where, variously Romania, Hungary, Germany and Austria, when, the War, (only his mother survived the concentration camps from his Jewish family), the Cold War, the 50s, 60s and 70s, what, as he moved through electronic and the Cologne School, to “micropolyphony” and then “polyrhythm”, all tumble out of his music like an avant garde encyclopedia. Know all those sounds that inhabit movie and TV soundtracks, when the creatives what to think big, go cosmic or generally scare the pants off you. Ligeti kicked it off, when Kubrick nicked his grooves for 2001. Music as texture. He even looks the part.

One more thing before I end this wall of pretentious guff. He always knew when to stop. Twenty minutes tops, even for the concertos. Most works clock in under ten minutes. Even opera Le Grande Macabre is under two hours. Genius.

The first concert kicked off with the Poeme symphonique for 100 metronomes. Yep there are 100 metronomes on stage set up with different beats. The performers skip on and set them off. Randomly. Of course it’s a joke, intended to explore the notion of chance in music (a la John Cage) but it becomes hypnotic, even a bit tuneful as patterns emerge from the chaos, and the gambler in me was desperate to have a punt on the last metronome clicking as it were. The survivor. An important concept for Ligeti given his personal history.

Pierre- Laurent Aimard was joined by regular collaborator Tamara Stefanovich for the two player piano pieces which preceded the Etudes. The first, Monument, sets up a cyclical rhythmic pattern which is then toppled with both players ending up at the very top of the keyboard. The second is an homage to minimalists Reich and Riley, fast scales and arpeggios with a backdrop of “silent” keys. This ends up in the bass. The third, Motion, is a canon, if you concentrate, which echoes the first piece.

The Trio is apparently an homage to Brahms. Search me. I suppose it does have a more Romantic structure than the polyrhythmic later Ligeti pieces. There is a sonata form opening, followed by a rapid ostinato with folky tunes wrapped around it, then a crooked march and a finale nicked from chords in Beethoven’s Les Adieux sonata. The main interest lies in the way the natural horn, with no keys and therefore lots of “out-of-tune” strange notes contrasts with the mannered piano, leaving the violin to hop between the two given its ability to produce natural harmonics. Since Ligeti dedicated his horn concerto (heard in the last concert) to Marie-Luise Neunecker, PL Aimard is the towering interpreter of Ligeti’s piano music and Pat Kop is my absolute favourite violinist in C20 music, there is no way this could have been bettered.

Then the fun started as PL Aimard and Daniel Ciampollini gave us a short rendition of Reich’s Clapping Music, (if you don’t know it the clue is in the title), which segued into Liget’s eighth Etude with Mr Ciampollini playing around it on his percussion kit, Nancarrow wrote his 49 Etudes for player piano because they were unplayable. Not so it seems, for these two particular studies, when four hands get involved. Then our percussionist interrupted on PL Aimard’s piano, and then both page turners, so all five were dinking out a version of the metronome piece that kicked things off. It was very droll though I admit you had to be there. Finally a dressed down version of Ligeti’s fourth etude.

Who knew classical music could be this much fun? OK maybe fun is stretching it but this whole performance emphasised the sharp humour which underpins Liget’s work as well as being a showcase for his rhythmic genius.

The next (free) concert was in the Purcell Room and involved students from the Royal College of Music. It mixed up some of the later solo Ligeti works with some from his early days in Romania and Hungary. As is always the case with RCM students the performance was at a very high level, better than many “professional” equivalents. Indeed this bunch already, largely, are on the circuit already. They all have jaw-droppingly impressive CV’s. I would single anyone out – they were all marvellous.

I heard the solo Cello sonata recently (Peter Wispelwey (cellist) at Kings Place review ****). It has been a nailed on cello classic since its premiere in 1979, though it was written in 1954. It was initially banned in Hungary by the “Composers Union”, a Stalinist censor. Two movements, a Dialogo, a conversation between a man and a woman, two ostinatos alternating between the upper and lower registers, and a Capriccio which has all sorts of thrilling extended techniques. (As an aside it would have been great to have recruited a cellist to the weekend cause to have a crack at the Cello Concerto with its bonkers high sustain at the end of the first movement).

The Ballad and Dance (1948) echoes Bartok with its loose transcriptions of Romanian folk songs. It is as easy to listen to as it sounds. Ligeti went on to explore Romanian folk songs in his Concert Romanesc (which sounds about as un-Modern and late C19 as it is possible to get).

Continuum was written for a two-manual harpsichord which can’t get up to much dynamically. The idea is that the notes are played so fast that the rhythm melts into a continuous blur. Almost to stasis. It looks and sounds like hard work to play but Tipwatooo Aramwittaya, (who appears to have medicine to fall back on if music and performance doesn’t pan out, which it will), was as cool as a cucumber. Like much of Ligeti the sounds are viscerally arresting but this is not mere novelty. Apparently it has been adapted for barrel organ to make it even simpler and even faster. The Passacaglia Ungherese, in contrast, is a repeated four bar descending ostinato intended to mimic the ground bass of the Baroque and was intended as a p*ss-take for his students, and those of us today, who love to keep moving to those Baroque grooves. It has some dancey counterpoints, obviously, and is marvellous. I need a recording.

The Musica Ricerta, like the Cello sonata, is a kind of experimental training work that Ligeti wrote in Hungary in the early 1950s away from the gaze of the censors. In each of the eleven pieces he places various restrictions on pitch, intervals and rhythms. they get sequentially more complicated as the number of pitch classes increases from the basic A in the first piece. Music for the brain for sure, but, as ever, Ligeti doesn’t skimp on the aesthetic. He loved sound you see.

This brings me neatly to the concert devoted to Ligeti’s 18 Etudes set across three books, started in 1985 and completed in 2001, his final work. All the influences on his “final late” period are there, central European folk music, Debussy, fractals, African cross-rhythms and Conlon Nancarrow. They are fiendishly difficult to play as Ligeti explores the entire range and possibility of the piano and piles layer upon layer of music. A fair few have a hectic, even aggressive quality, as they pile up into a rapid resolve but there are also poetic moments. There is a reason why M. Aimard is the pre-eminent performer of these pieces and the full house here was privileged to witness it. One of the best concerts I have ever attended.

The final concert expanded the player forces with the Aurora Orchestra under Nicholas Collon taking to the stage. The Chamber Concerto is a nailed on classic of the modern era, small-scale orchestra, 20 minutes in length, (no-one dares go further in new music, if only because it won’t get performed), and boundary-pushing. The opening movement has the instruments sliding around until they bash up against each other, then the winds sing out, before it all subsides. The second movements is a kind of mashed up Romantic fantasia which goes a bit awry, to be followed by a mechanical march, a clock factory under attack. The Presto finale is in a similar vein though ends perkily. If you ask me it is like a mini Rite of Spring, though as if some talented musicologist had discovered a partially burnt, muddled up copy of the score many years later. I am still trying to work it out.

The Piano Concerto is an even more uncompromising chap. Movements 1, 3 and 5, all quickest require the pianist to set the rhythms against which the orchestra adds snatches of melody. The second and fourth movements are more of a partnership. In the second the silly instruments, whistles and ocarinas, enter the chorale and in the fourth Ligeti sets up his head-spinning fractal structures. It is pretty quirky overall, sometimes confrontational, but immensely rich. I think it was the one piece over the weekend which really pushed the audience.

The Hamburgisches Konzert, Horn Concerto, was written for Marie-Luise Neunecker and in honour of Hamburg where he lived for 30 years. It is written, in part, for natural horn and exploits the strange harmonies which can emerge from the pure overtones of that beast. Finding out what sounds can do is part of the modern classical world but Ligeti, even here, never forgot to ensure this was set in a profoundly musical context. There are seven short movements. The soloist shifts between natural and valved horns, the four horn players in the orchestra, (all fine players, Pip Eastop, James Pillai, Ursula Monberg and Hugh Sisley), accompany on natural horns, the orchestra, except in the fourth movement takes a back seat. Now there is no doubt that the horn sound is a beautiful, extraordinary and eerie thing, (listen to Britten’s Serenade for a more comfortable alternative), but, to be fair, it can’t get up to much. But what it can do is showcased in this concerto and Ms Neunecker is probably the best person on the planet to show us how.

Having said that it was the Violin Concerto that brought the house down. Pat Kop is a magnetic stage personality, as she skips about, every inch the gypsy fiddler, in bare feet. The work is meat and drink for her, she even chucked in her own, entirely sympathetic cadenza, roping in the lead violin of Alexandra Wood. But the Aurora Orchestra also rose to the occasion. There are all sorts of non-standard tunings at work here, in the brass, in the woodwinds, even in one violin and viola. And, of course, the soloist, if they know what they are about, can bounce around to exploit the strange harmonics as GL intended. There are five movements, all of which exploit the coincidences, but the clarity of the interplay makes these sound more chamber-like than its two concerto peers. And dear reader there are passages, like the Aria at the beginning of the second movement, that are not at all scary. I promise. It’s a masterpiece I reckon.

So there you have. Possibly the best composer of the latter half of the C20 shown off to stunning effect by musicians who clearly love his work. You could feel the buzz in the room/s. The Barbican, courtesy of the BBCSO, has a “Total Immersion” day devoted to Ligeti on 2nd March next year, which repeats some of these works but offers up some choral and larger scale orchestra works. Do go.