London Philharmonic Orchestra, Vladimir Jurowski, The Swingles, London Philharmonic Choir

Royal Festival Hall, 8th December 2018

- Elizabeth Atherton – soprano

- Maria Ostroukhova – mezzo-soprano

- Sam Furness – tenor

- Joel Williams – tenor

- Theodore Platt – baritone

- Joshua Bloom – bass

- Stravinsky – Variations (Aldous Huxley in Memoriam)

- Stravinsky – Threni

- Stravinsky – Tango

- Luciano Berio – Sinfonia

I cannot describe how excited I was about this concert, and not just because it represented the final instalment of the year long Changing Faces: Stravinsky’s Journey retrospective in which the London Philharmonic Orchestra (amongst others) has performed the vast majority of Stravinsky’s large scale orchestral and choral works, as well as many of the ballets at operas, at the South Bank. Here, in the final instalment, we were treated to a pair of his late “serial” works for orchestra, Variations, and for choir, Threni, as well as a few welcome surprises. Of course Stravinsky being Stravinsky this was not the miserable, astringent, intellectual fare of the Second Viennesers but an altogether more satisfying feast.

However the real reason for the Tourist’s frenzied anticipation, (OK maybe that was a bit of an exaggeration), was the performance of Berio’s masterpiece Sinfonia. The Tourist hopes to soldier on for a few more years yet and pack in a little more exploration and understanding, (though he feels he may have come close to mapping out the boundaries of what he “likes” and “dislikes”), but he is pretty sure that Sinfonia would be a shoe-in for his list of top ten greatest “classical” music works. Actually, just for fun and in festive spirit, here is the current state of play on that work in progress. In no particular order. Only one piece per composer. Oh and there are 14. Like I say a work in progress.

- Luciano Berio – Sinfonia

- Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No 7

- Isaac Albeniz – Iberia

- Antonio Vivaldi – The Four Seasons

- Arvo Part – Fratres

- Johann Sebastian Bach – Sonatas and Partitas for Violin

- Benjamin Britten – Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings

- Gyorgy Ligeti – Etudes

- Claudio Monteverdi – Vespers

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Symphony No 41

- Steve Reich – Drumming

- Dmitry Shostakovich – Symphony No 10

- Igor Stravinsky – The Rite of Spring

- William Byrd – Mass For 5 Voices

I’ll think you will agree there is nothing intimidating here and, if I say so myself, it contains a fair smattering of “popular” hits. Romantic composers are conspicuous by their absence and, for those of a certain age, in the words of Snap!, Rhythm is a Dancer here. Hopefully though you can see the Tourist is not the type to show off with the obscure or arcane. So, dear reader, if you are “new” to classical music, I say why not take the plunge with a few of these pumping beats.

Anyway back to the business in hand. Sinfonia was originally written for The Swingle Singers, the forerunner of this evening’s revamped ensemble and frankly the only group capable of doing it justice, but Vladimir Jurowski and the LPO still had a lot of work to do to pull this off. I have said before that Mr Jurowski, on his day and in the right repertoire, is as good as any conductor I have ever heard, including Simon Rattle, Bernard Haitink, Claudio Abbado, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Colin Davies, Mariss Jansons, Georg Solti and John Eliot Gardiner. Any absentees you spot reflects the fact I either haven’t heard them or don’t like them. I have never heard Riccardo Chailly conduct but know I should and that Kirill Petrenko, based on the Beethoven 7 with the BPO at the Proms in September, plainly knows what he is about. F*ck me was that good.

When Mr Jurowski sets up shop permanently in Berlin in a couple of years it will be a blow to London. As will the departure of Esa-Pekka Salonen from the Philharmonia. I imagine there are plenty of people who couldn’t give a flying f*ck about the artistic leadership of London’s classical music ensembles and indeed the future direction of the South Bank but, trust me, culture, even when “highbrow”, really matters. I still have this uncomfortable feeling that olde England is now determined to plough on with making a right b*llocks of everything, from which our abiding advantage, our language, will not be sufficient to save us. We went down the toilet, geopolitically, for most of the Late Middle Ages until a few bright sparks in the C17 and beyond came up with the idea of combining capital, education and technology to travel round the world nicking land, stuff and people. We have been doing the same, that is falling back a little, for a few decades now. We still do many things well but only if we welcome innovation, capital and people. Thus changing who “we” are. Which “we” have always done. Cutting “ourselves” off is not, and has never been, an option.

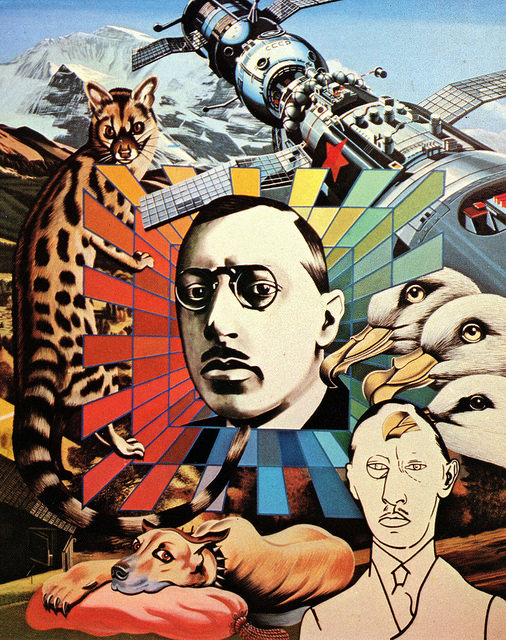

Jesus what has got into me. Back to Vladimir and the LPO. He is a dab hand in just about anything Russian, and I include Stravinsky in that, but, over the past few years, he, and the orchestra have also sprung a fair few surprises. To which we can now add the Sinfonia. Berio composed the piece in 1968/69 to celebrate the 125th year of the New York Phil. Defiantly post-serial, (old Luciano had a few choice words to say about serial music even when embraced by Stravinsky), post-modern, (that being all the rage then as it still is now), forged in the white heat of the intellectual, and actual, revolutions of the late 1960s, (I realise this is not getting a bit w*anky), you might be forgiven for thinking that Sinfonia will be some arty-farty, hippy inflected guff that hasn’t aged well.

Especially when you start reading about its structure. Originally four movements, which Berio quickly expanded to five with a sort of coda that commented on the previous four, it begins with texts from Le cru et le cuit (The Raw and the Cooked) from French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss. Yep that Claude Levi-Strauss. Up there with those other Gallic sorts like Foucault, Derrida, Lacan and Barthes, and worst still those dubious German types like the Frankfurt School, who we Brits are rightly suspicious of. Drinking wine, smoking odd cigarettes, carrying copies of Das Kapital, and, worst of all, thinking and talking all day. Still they, and their descendants, will never infect the stout yeomanry of the English shires with their clever dick mumbo jumbo once we get shot of “Europe”.

Now C L-S had a theory that myths were structured in “musical” form, following either a fugal or a sonata construction. Nope me neither. Anyway apparently there were exceptions to the rule for myths about the origins of water and this is what Berio alighted on for Movement I. Which I guess means it has no form. It is a kind of slow threnody punctuated by all manner of bangs and wallops with the eight amplified voices chiming in with the text. Near the end a piano gets a look in leading a percussive Bugs Bunny scramble. It is a bit nuts. C L-S was baffled by where LB was coming from. So don’t despair if you are too.

But it kind of has a way of drawing you in. Berio saw a sinfonia in a very literal sense, from the ancient Greek, a “sounding together”. A layering of sound, instrumental and vocal, often cacophonous for sure but always individually textured. And most importantly searching for “a balance” which is what distinguishes it from the plink-plonk-fizz of much of the contemporary classical music that preceded it. Thus, in movement II, Berio takes one of his own chamber works O King, for five instruments and mezzo-soprano, and recasts it for the orchestra. It is a kind of lament based on two whole tone scales where the singers gradually build up the name of Martin Luther King. Instrumental and vocal whoops representing the vowels and consonants contrast with a shimmering orchestral backdrop.

All clear. On to Movement III then. “In ruling fliessener Bewegung”. In quiet flowing movement. The sub-title of the third movement scherzo of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony. For this, cut-up and re-orchestrated, is what, famously, sits behind the movement. Alongside countless other snatches of classical music through history. Debussy, Ravel, Berg, Beethoven, Bach, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Webern, Hindemith, Strauss, Berlioz, Stockhausen, Boulez and many, many more. And, because I guess it seemed to need it, fragments of Beckett’s The Unnameable are also sung, spoken and stuttered, alongside, behind or over the top of the music. There is also a bit of Joyce, some graffiti quotes, even Berio’s own diary entries.

It is a quite extraordinary experience, unnerving, hilarious, annoying, enigmatic and occasionally sublime, a history of music threaded through what might be someone’s personal history. At first it appears to be a mess, a collage with no structure or pattern. But hang on. Didn’t that musical quotation seem to echo the Mahler? And why did that phrase, which made me laugh out loud, jump out? Once again you are drawn in, looking for something, “keeping going” as Berio would have it, whilst all around “civilisation” is threatened by the forces of repression.

I know, I know. Now I sound like a right dick. And yes, just maybe it is a little bit still of its time, But it is just such a jaw-droopingly extraordinary sound-world, so rich, so un-musical yet so musical., that this must be forgiven. Movement IV returns to the tonality of the second movement with a quotation, again from Mahler’s Resurrection, setting up the voices to wander off into another, choral, world. Had enough of quotation? Berio hasn’t, as Movement V then packs in the mother of self-referencing, meta “analysis” of everything that has gone before. Your ears and brain will be processing the aural information, and telling you things, even if you don’t know how and why it is happening.

Not for one single second of the whole work does any of this feel like hard work. Quite the opposite. There is tension and resolution. It is uplifting even as it is disturbing. And very funny even as it mystifies. And I can’t imagine a better performance than here. I am listening to the recommended recording as I write. The Orchestre National de France under Pierre Boulez with the New Swingle Singers (including founder Ward Swingle himself). The LPO and current Swingles sounded better. And that from somewhere in the back stalls of the Festival Hall. Maybe it was the excitement of it being live but any way up it was tremendous. In the third movement especially the lilt of the Mahler scherzo really was there throughout but it never obscured the other musical phrases. Seating the Swingles behind the first row of strings, though still forcefully amplified, ensured they were both integrated with, and punchily counter-pointed, to the LPO. How so much detail was conjured from so much confusion was, literally, uncanny. I gather there are times when Vladimir Jurowski’s excessive precision can annoy some punters. Not me. And definitely not here.

And a shout out to the sound engineers at work for the performance. I can’t find a reference in the programme. Well done though. Unlike the BBC who managed to nonce up the Radio 3 recording.

So you will have to find another performance but give it a whirl if you can. half an hour of your life that you will never get back. But in a good way. A really, really, really good way.

What about the Stravinsky? Well the appetiser, the Variations in memory of Aldous Huxley who died on the same day that JFK was assassinated, is a twelve note tone row which is subject to a series of eleven mechanical “variations”, inversion, retrograde, and the like, with each variation made up of twelve orchestral parts and each having twelve beats in a metre. It was IS’s last orchestral score. Apparently Huxley himself would have had no truck with such serial musing but, coming in at just five minutes, it was interesting at the time if thereafter, forgettable, apart maybe from the astonishing 12 violin variation – like having Xenakis in da house.

The Threni however is an altogether more substantial affair, IS’s longest serial work, in three parts, each drawing on selected Latin verses from the Book of Lamentations, with the middle section by far the most substantial, It makes much use of sung Hebrew letters. There is no particular narrative, it not being intended for liturgy, and it wheels out a biggish orchestra, (including a sarrusophone and flugelhorn), six soloists and a hefty choir, though tutti are frugally used. It is serial in construction but, and this is where old Igor really shows his musical cunning, it doesn’t really sound like it. It is anchored in the more tonal elements of the twelve note row and regularly allows the dissonance to resolve in consonant highlights. The orchestral and choral textures are distinct and Stravinsky chucks in all manner of single tone chants and antiphonal exchanges such that, on occasion, it really does sound like the high polyphony of Tallis, Byrd and Palestrina, even if it plainly isn’t. Don’t get me wrong. It still has all the necessary austere, other-worldly “tunelessness” you might expect from a twelve tone choral work. It just isn’t ugly. Quite the reverse in many places. Full of drama and contrast. I am not saying you would want to chopping the veg or driving home for Christmas with this in the background, just that it is very different from what you might expect. It is not quite up to the neo-classical Symphony of Psalms from some 30 years earlier but is definitely up there with IS’s swan-song the Requiem Canticles.

IS drew inspiration from an earlier Lamentations of Jeremiah published in 1942 by Czech-Austrian composer Ernst Krenek which more explicitly used twelve tone technique combined with Renaissance modal counterpoint. (Don’t worry Krenek himself spent a couple of years aping Stravinsky’s neo-classicism before he became a disciple of Schoenberg). Whilst the first performance of Threni in Venice in 1958 went off well, the premiere in Paris a couple of months later was a right dog’s dinner with Stravinsky, who conducted, getting into a slanging match of recrimination with his bessie Robert Craft ,who was supposed to have prepared the orchestra, and Piere Boulez who drafted in the woefully under-rehearsed soloists. The chorus probably wasn’t best amused when presented with the original score which was, shall we say, scantily clad in the bar-line department. Mind you given the dynamic range that IS requests of the choir that might have been the least of their problems.

No such shenanigans with the LPO and Mr Jurowski who delivered a beautifully layered interpretation with the LPO chorus, split antiphonally, as persuasive as I had ever heard. In fact they made it look and sound easy which, as the paucity of live interpretations reminds us, it most certainly is not. I would point to Joshua Bloom and late replacement Sam Furness as the pick of the soloists, but then again then had more time to shine in the central passages.

Prior to the Sinfonia the Swingles served up a vocal arrangement of Stravinsky’s Tango, complete with beatbox, which I think improved on the orchestral and piano versions previously heard in this Series. And, after another a cappella treat in the form of the Piazzolla Libertango, the LPO encored with Stravinsky’s Circus Polka to send us on our way with a Yo Ho Ho.

Spare a thought though for Maxim Mikhailov the Russian bass, from a long line of Russian basses, who was booked for the Threni solo part and who sang in the Requiem Canticles here a few weeks ago. He died on 21st November. Seems like he was beaten up on a Moscow street. FFS.