The Tragedy of King Richard the Second

Almeida Theatre, 9th January 2019

Vain, frivolous, self pitying, introverted. Richard II doesn’t come across too well at the beginning of this play, Shakespeare’s first instalment of his histories that chart the origins of the “War of the Roses” and end with the death of Richard III and accession of Henry VII. Yet by the close of Richard II, acutely aware of his own fate, we see, not a different person, but a man who finally realises how his actions, as well as those of his aristocratic rivals, brought him to where he is. The distinction in Joe Hill-Gibbons’s quick-fire take on his tragedy is that his nemesis, Bolingbroke, who becomes Henry IV, travels in the entirely opposite direction, secure in his right to reclaim his titles, and then the throne, on returning from banishment, he quickly descends into a vacillating arbitrator of facile dispute.

The play highlights the fact that political power often overwhelms those that seek to wield it, as competing interests compromise consensus, a valuable lesson for our troubled times. Kings, and their democratic equivalents, are those that divvy up the prizes, once land, now patronage, to lords and their modern equivalents. These may owe allegiance but they can get mighty uppity if they feel taken for granted or hard done by. The joy, and instruction, of Shakespeare’s history plays, which examine the delicate balance between those that lead and those that keep them there, is that the deadly embrace continues to this day. Only now, we, the hot-polloi, have the right to stick our oar in as well. Apparently the “will of the people”, even if no-one knows what it is, least of all the people, is now the only source of legitimacy. Hmmmm.

In order to get to the heart of this tragedy though the production does take a few liberties with us the audience. First off it starts at the end, kind of, with Simon Russell Beale’s Richard II pronouncing “I have been studying how I may compare/This prison where I live unto the world.” Famous soliloquy dispatched what follows might be, TV drama style, his flashback.

Richard II is written entirely in patterned verse, (as are the first and third parts of Henry VI and the ropey King John), even down to the gardeners who get to comment, memorably, on the state of the country under their warring betters. The verse remains intact through the 100 minutes of the production, (with a few pointed additions), but its rhythms take something of a back seat. Especially in the first half hour or so, when the lines are delivered at breakneck speed. Not a problem for Simon Russell Beale as Richard II or Leo Bill as Bolingbroke (whose lines are deliberately less florid and more direct than Richard’s). However one or two of the less seasoned members of the cast snatched a little, noticeably in the arbitration, tournament and banishment scenes. The rhythm settles down by the time we get to John of Gaunt’s lament (“this sceptred isle …. now bound in with shame … hath made a shameful conquest of itself”; the speech is not about how great we are but how we manage to f*ck it all up, that, and a couple of lines of blatant anti-Semitism). Even then you have to keep your ears open and your wits about you.

There is also, (not unreasonably since, as events pile up, it really works as a conceit, especially when combined with some inspired choreography), a lot of character doubling and more. The Tourist always recommends that Shakespeare is best consumed following a little homework into context and synopsis. A quick Google on the way in is all that is required, as witness BUD who was my guest here, even for those who think they know the plot backwards. Ironing out your Aumerle (here Martins Imhangbe) from your Carlisle (Natalie Klamar) from your York (John Mackay) from your Northumberland (Robin Weaver) always pays dividends. Knowing which aristo is on which side has historically always been a sound real life lesson as it happens: knowing why is a bonus.

Fans of “historical” Shakespeare, whatever that is, are also in for a bit of a shock here. ULTZ’s set is a stark, bare cube, comprised of brushed metal panels riveted together, topped by a frosted glass ceiling. It serves very well as prison cell, less figuratively as castle, garden or jousting field. As a way of showing how power plays out in claustrophobic rooms and crushes those who exercise it, it does the business though thank you very much, and, remember, we might be in the prison of Dickie’s mind anyway.

This set works especially well when combined with James Farncombe’s bold lighting design. JH-G had a huge cast on his last outing and a magnificent recreation of a Soho drinking den at the close of WWII courtesy of Lizzie Clachlan and a fat lot of good that did him. It was awful. Though that was more the play’s fault than his. Here he is on much firmer ground as he was with his excellent Midsummer Night’s Dream and measure for Measure at the Young Vic. His fascination with soil continues, there are buckets of earth, water and blood lined up and neatly notated at the back of the stage. I like to think they symbolised “this England”: they certainly left SRB needing a hot shower post curtain call.

Of the supporting cast I was particularly taken with Saskia Reeves, as I always am, who got to be the argumentative Mowbray, the unfortunate Bushy, (with Martins Imhangbe playing Bagot, his head-losing mate), the other favourite Green, and the Duchess of York, and Joseph Mydell, a composed Gaunt as well as Bolingbroke sidekick Willoughby. Various explicit nobles on both sides are excised from this reading, as is the Queen amongst others, and, should a fill-in be required, out stepped one of the cast from the “chorus”-like crowd. Brutal it may be for purists, but in terms of reinforcing the hurtling momentum, very effective.

Leo Bill once again shows why JH-G has faith in his Shakespearean abilities, but it is Simon Russell Beale who carries the weight of the production on his shoulders. How he ensures that we not only take in but understand the impact of every line he utters is a wonder, especially in the return to England and Flint Castle surrender scenes. Even when he wasn’t dashing out his metaphor and simile strewn lines in double quick time, and wasn’t soaked through covered in mud, this was a cracking performance. The fact that he was, and that we can still savour Shakespeare’s language, and sense the difference between the body politic and the body natural, (the, er, embodiment of the medieval king), shows again why he is now unarguably our greatest living Shakespearean actor.

In this performance Richard’s early, flawed, decision-making seems less vanity or indecisiveness and more high-handed hauteur, the desire just to get the job done regardless of consequences. I’m the king, by divine right, so of course I know what to do. There isn’t much in the way of Christ-like martyrdom here as there was in David Tennant’s guilt-ridden 2013 RSC take or in Ben Whishaw’s petulant Hollow Crown reading. No white robes or flowing mane of hair here. The fact that SRB is “too old”, the real Dickie was in his early thirties for the last two years of his reign when the play is set, and that he, and Leo Bill, look nothing like the generally accepted take on the characters, only adds to the universality of the message.

The early years of the actual Richard’s reign weren’t too jolly for him by all accounts. Acceding to the throne aged just 10, with a bunch of nobles preferring a series of ruling councils to a regency under Uncle John (of Gaunt), the Hundred Years War with France not going England’s way, Scotland and Ireland playing up and labour growing its share of the prosperity pot at the expense of landed capital (the Black Death had led to a sharp spike in agricultural wages). In 1381 the Peasants even had the temerity to Revolt. By now though the young king was throwing his weight around but many of the entitled aristos, (whom we meet in the play), didn’t hold with the company he kept and in 1387 the so called Lords Appellant, (Gloucester, Surrey, Warwick, Bolingbroke and Mowbray), seized control and one by one, tried and disposed of Richard’s favourites.

By 1389 Richard was back in control, with Gaunt’s oversight, and, for a few years, got on with the job. But he never forgot what his opponents had done and, come 1397 he started taking revenge, notably, on Gloucester, his uncle, who he had bumped off. This is often where the play steps off with the King’s bloody guilt informing the four short years before his death, probably by starvation, after Bolingbroke’s usurpation.

Richard was allegedly a good looking lad, see above, who believed absolutely in his divine right to rule at the expense of the uppity Lords. He wasn’t a warrior, rather a man of art and culture, aloof and surrounded by a close knit retinue. As with all the big players in the history plays, our perception of Richard II, is though to some degree shaped by the Bard’s not always favourable publicity (that’s if you have any view at all of course). Via his favourite contemporary historian Raphael Holinshed. There was apparently a time when historians thought Richard was insane: now the wisdom is that he had some sort of personality disorder that contributed to his downfall.

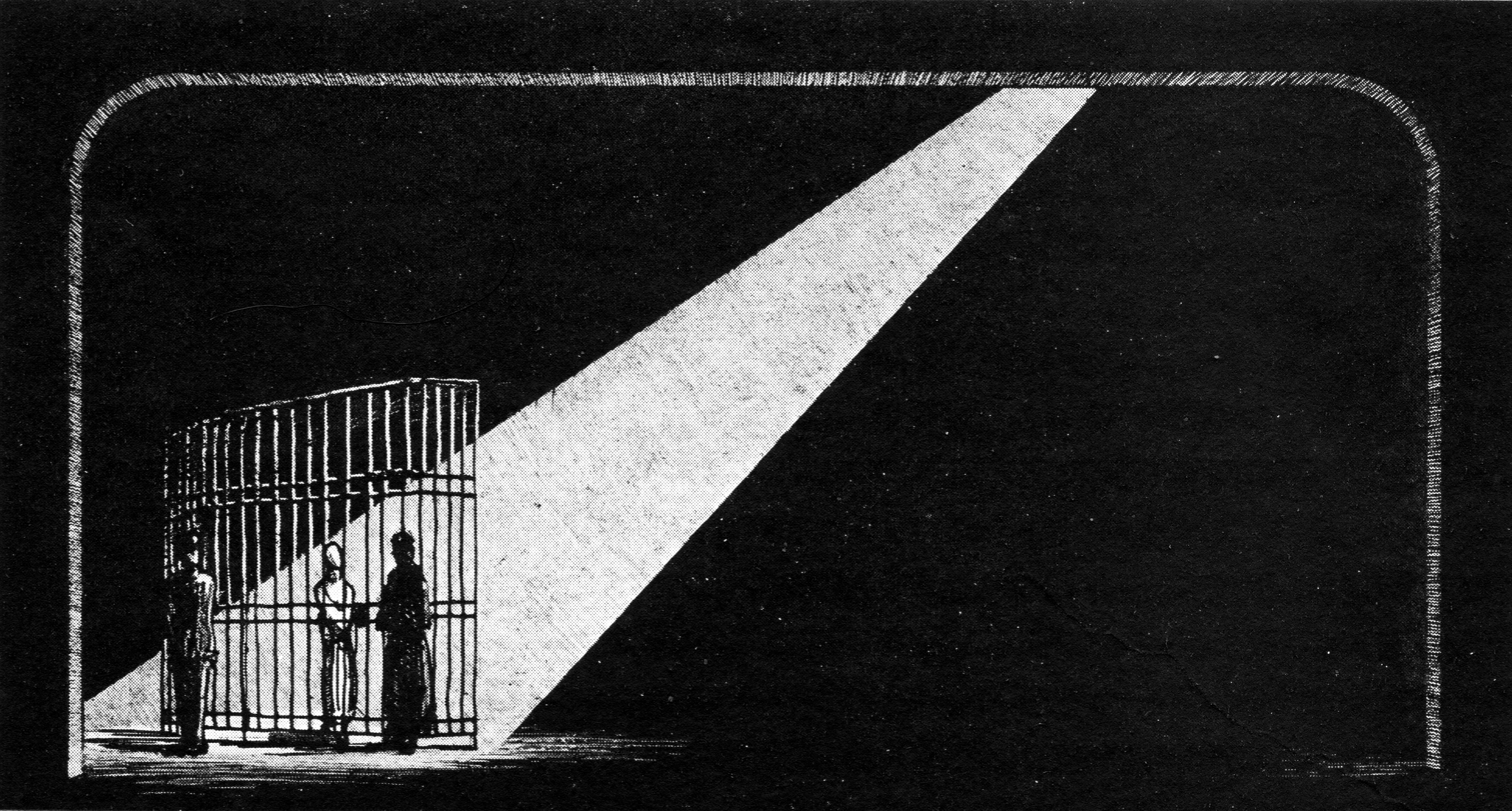

Mind you if you were locked up in solitary confinement you might well lose the plot. There is an extract in the programme taken from Five Unforgettable Stories from Inside Solitary Confinement by Jean Casella and James Ridgeway from Solitary Watch. Solitary Watch tracks the estimated more than 80.000 prisoners in the US system held in solitary confinement on an average day. Here four prisoners eloquently describe their experience. Left me speechless. 80,000. That’s not a typo. Google it.

So another success from the Almeida hit factory, another masterclass from Simon Russell Beale and another validation of Joe Hill-Gibbons radical(ish) way with Shakespeare. BUD, whose first exposure this was to the history plays, agreed. Mind you there isn’t much in this world that he can’t size up within 5 minutes of first introduction.

There is probably a case for JH-G slowing down proceedings just a little, another 15 minutes wouldn’t have been a stretch, just to let the poetry work a bit more magic, give a little more complexity to Bolingbroke and the nobles, and draw out more from the themes. And the stylised, expressionist visual concepts won’t, (and haven’t), pleased everyone. But as a coruscating denunciation of the perennial failure of the political class, you want see much better on a stage even if it was written over 420 years ago.