BBC Symphony Orchestra, Sakari Oramo, Vilde Frang (violin)

Barbican Hall, 21st March 2018

- Anna Clyne – This Midnight Hour

- Benjamin Britten – Violin Concerto, Op 15

- Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No 6 in F major “Pastoral”, Op 68

The Violin Concerto is one of those Britten pieces that takes a bit of time to get used to. It was written in 1939 so contains plenty of the youthful flashiness, and debts to Stravinsky, which characterise early BB, but with a more serious intent which reflects his admiration for Alban Berg, whose own Violin Concerto, was the last in a frustratingly thin oeuvre. BB attended the posthumous premiere of Berg’s masterpiece in 1936, in Barcelona in the shadow of the forthcoming Spanish Civil War, as well as two further performances later in the year. Understandably he was mightily impressed.

BB’s own concerto was premiered in New York in March 1940 by the Philharmonic under John Barbirolli, given that he and Peter Pears were stuck there following the outbreak of war. The British premiere was in April 1941 in BB’s absence. Despite BB’s revisions in 1950, 1954 and 1965, which brings a little more of the late Britten’s soundworld to the violin part, the piece has historically been more admired than loved, but it has developed a bit more of a following in recent years.

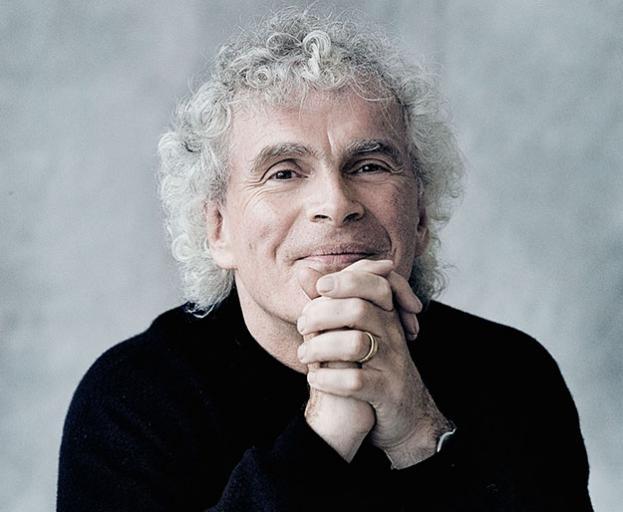

Which means that some of today’s finest violinists have taken up the BB VC cause. These include Janine Jansen who played the piece with the LSO last year under Semyon Bychkov in this hall last year. This is not a concerto full of showy virtuosity, the soloist works on the ideas with the orchestra, but it does require a formidable technique. Ms Jansen certainly has that but the performance overall was a bit more athletic and weighty than I might have liked (though maybe that was the influence of the Mahler on the bill).

In contrast Vilde Frang, who has also recently recorded the piece, seemed a little bit more delicate, most obviously in the pianissimo sections, and the double stopping, of which there is a surfeit in the Scherzo, more Baroqueish than Modernist. This lighter, though still enthralling touch, made the final coda, constructed in BB’s favourite Passacaglia form, even more irresolute. a good thing in my book. The first movement, in sonata form, opens with a little rumble on the timps, then the bassoon takes up the tune, and then the rest of the orchestra, returning to it ostinato through the movement, whilst the violin moves in and out with its uneasy, song-like lament. The second theme is also martial in intent; there is a link to Shostakovich, but with more elegance and less hectoring. This theme is taken up by the violin, not the orchestra, in the recapitulation which ends with an unsteady coda. The second movement scherzo is spiky and Prokofievian in feel, with a very sinister transition to a tutti before ending with a cadenza, based on the first movement tunes, in which Ms Frang excelled. The ground bass which underpins the variations in the final movement is a bit wobbly in terms of tone, at one point D major triumphs, ending with a simple chant, over which the violin dances around, never quite closing out.

I think it is the uncertain tone, literally and metaphorically, that makes the BB VC seem like harder work than it actually is. Played like this though it is up there with the very best of BB’s works which require a full orchestra, the contemporary Sinfonia da Requiem and the War Requiem. It is a lot less knotty that the Cello Symphony that’s for sure. Having said that BB’s textures always work better for me in the pieces for smaller orchestras. I went back to the benchmark recording I have, the ECO under BB himself with Mark Lubotsky as soloist. Maybe I was just in a good mood at the concert but I reckon Ms Frang and Sakari Oramo gave them a pretty good run for their money, especially in the opening movement, which seemed to get to the point more quickly.

The BB VC was preceded by the London premiere of a 12 minute work written by Anna Clynne, British born now working in NYC. It was written for the Orchestre National d’Ille de France where she was resident composer. It is resolutely tonal and packs a hell of a punch. It is pretty sexy stuff too, as was her intention, based, as it is, on Baudelaire’s poe Harmonie du soir and one line from a poem by a chap called Jimenez about a nude lady running through the night. She packs a lot into the piece, kicking off with a rushing theme low down in the bass and cellos, moving to some sparkling woodwind, a slab of Brucknerian grandeur and then a Ravel like sharp waltz, before the whole thing seems to whirr around again. Apparently Ms Clyne notates her score with mood markings, intimate, melting, ominous, feverish, ferocious, aggressive, skittish, beautiful, eerie, which is easily comprehended. I have got much better at taking in contemporary compositions at the first, (and often only), outing, but this piece doesn’t require too much concentration, so immediate is its impact. Seems like the audience agreed judging by the reaction and deserved applause when Ms Clyne came out of the audience.

Which meant that, unusually, Beethoven took the back seat. Absolutely nothing wrong with Mr Oramo and the BBCSO’s take on the Pastoral but there wasn’t too much to get the pulse racing. The detail was there but the pacing was relaxed and the orchestra didn’t seem as engaged as when they are getting their teeth into unfamiliar repertoire or having to convince the big crowds at the Proms. Brooks babbled, birds sand, peasants partied, lambs gambolled, the storm came and went, but Mr Oramo didn’t seem to find the genuinely symphonic in the way others have. Still it’s Beethoven so pipe down Tourist and be happy with your lot.