The Tallis Scholars, Peter Phillips (director)

St John’s Smith Square, 31st March 2018

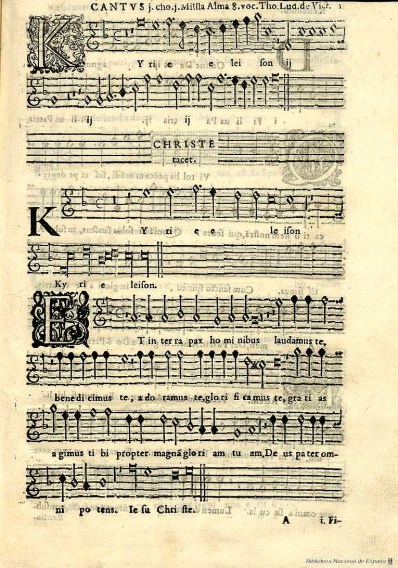

Tomas Luis de Victoria (1548-1611)

- Surrexit pastor bonus

- Vidi speciosam

- Magnificat for double choir

- Missa pro defunctis Requiem

Francisco Guerrero (1528-1599)

- Tota pulchra es

- Hei mihi, Domine

Alonso Lobo (1555 -1617)

- Versa est in luctum

Having dipped a toe into Early and Renaissance vocal music the Tourist probably finds himself listening to more than the average man on the street to Christian devotional music and Latin texts. This despite him being an avowed atheist and useless at languages. There is next to no cognitive dissonance arising from this set of circumstance, however, but he can now see;

- how the C16 and earlier man/woman on the street might get taken in by all the mumbo-jumbo given the power and beauty of the music (and art) that the Church offered (remember there were precious little other aural or visual stimuli to be had – no Candy Crush or Instagram in those days) and,

- how pointless it was setting it in a language said man/woman couldn’t understand leaving the door open for the Reformation to shake up the Catholic Church.

It has taken a bit of time but the Tourist has finally discovered the work of one Tomas Luis de Victoria thanks to the influence of some wise teachers. Snapped up a 10 CD disc by Ensemble Plus Ultra, a Gramophone Award Winner, for a bargain £30 after facing off the Amazon machine. I will likely die before I ever really get to grips with this music, (as for so much else), but there will be so much pleasure in the journey. Ensemble Plus Ultra are another in the long line of British early music vocal ensembles who, I expect, will have been inspired by the original wave of scholars and performers from the 1960s and 1970s, including our director for this evening, Peter Phillips, one of the grandaddies of the whole movement.

Now TVic was a big noise in C17 Spain, and along with Palestrina, based in Rome, and Orlando di Lasso, born in Mons in present day Belgium, but who worked all over Europe, was a major force in the Counter-Reformation when the Catholic church bit back. TVic was a performer and, helpfully, a priest but thankfully for us focussed on churning out compositions rather than taking confessions. I gather a fair bit is known about him, he worked in Rome for a spell before Philip II of Spain, the most important bloke in the world then with Spain at the height of its power, gave him the job of Chaplain to his sister, the Dowager Empress Maria in Madrid. This was Spain’s artistic Golden Age and these composers were a proud part of it.

I defy you note to be immediately drawn in by TVic’s grooves. The music is much more direct and “churchy”, with more affective melodies, than some of his European peers and predecessors. He is the master of manipulating, dividing and receding choirs. The polyphony is less complex than, say, Palestrina with more homophony, (everyone belting out the same text), but he creates some surprising textures and dissonances and a lot of melodic contrasts. He wasn’t averse to a bit of word-painting even though he only ever wrote sacred music.

The Surrexit pastor bonus is an Easter motet which is typical of TVic’s style, set for six voices which he combines in all manner of ways in just 3 minutes. It kicks off with dramatic soprano and the higher registers swirl around the lower basses. The Vidi speciosam is similarly scored and uses a popular Old Testament setting, (which also formed the basis for a TVic Mass). It starts off in a fairly restrained way but gradually builds out so that at times it feels like the whole of Wembley Stadium is in the room. TVic churned out 18 versions of the Magnificat but this one, Primi Toni, for two four part choirs, is entirely polyphonic with no plainchant intervals, though it is easy to hear the chant it comes from. There are a fair few effects along the way.

Francisco Guerrero was born and died in Seville, and spent most of his working life in Spain, but when he did venture abroad he packed a lot in, what with being attacked by pirates twice when coming back from the Holy Land, and landing up in debtor’s prison. Unlike TVic he wrote secular pieces in addition to motets and masses, though he also kept it homophonic and had a flair for drama. The first motet here, Toto pulchra es, is drawn from the same source as the Vidi speciosam and is similarly an paean of praise to the Virgin Mary, who was guaranteed to work the church fellas up into a right lather at that time. The second piece, Hei mihi, Domine is rather different with sharp contrasts and syncopated rhythms conjuring up a more impassioned plea for mercy in this Matins for the Dead.

Alonso Lobo was Guerrero’s sidekick at Seville Cathedral and took over when the old boy went walkabout. This chart-topping motet, Versa est in luctum, was written for Philip II’s funeral, and it shows with full-on “oh woe is us” grief-stricken passages from the book of Job apparently. It is his best known number. He had a spell in Toledo, (a city everyone must go to once in their life), and, in his life, was rated equally with TVic and Palestrina.

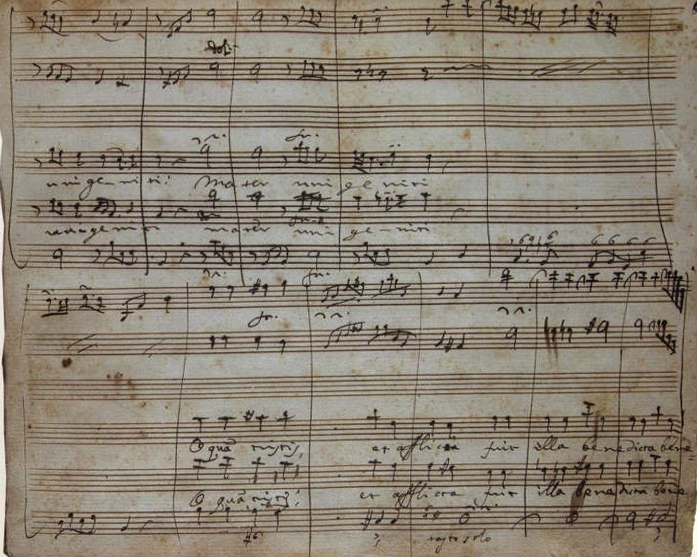

The meat of the concert was TVic’s Mass written on the death of his beloved employer Dowager Empress Maria. There are a fair few TVic masses, and I have only just started to get to grips with them, but if you need somewhere to start this might be it. TVic had 16 voices at his disposal when writing the piece and he took full advantage with six parts. It is a Mass for the Dead, a Requiem, based on the ancient plainchant melody, which becomes an immense structure in TVic’s hands. He also throws in a Versa est in luctum a la the Lobo motet and a lesson, Taedet animam meam, to serve up a near 50 minute funeral celebration for that is how it feels in spite of the subject. Old Dowager Maria may have shuffled off this mortal coil but in the afterlife she had loads to look forward to based on this music.

Obviously the Tallis Scholars under PP were perfect. They create a big sound but you are always aware of where the music comes from and what its point is and there’s no fancy grandstanding. It is hard sometimes in these concerts not to give in completely to the wall of sound and float off, but the Scholars in tandem with the composers, especially TVic provide enough contrast and drama to bring you back inside the music, its structure and its story.