The Tourist has been shockingly remiss so far this year in documenting his adventures in the visual and plastic arts. Some plagiarised comments on the I Am Ashurbanipal survey of Assyrian art at the British Museum aside, I have failed to document any other exhibition visits. So, for the sake of completeness, here are some brief comments lest I forget. Sorry reader. This is for me not you.

Figure, Totem, Beast: Sculpture in Britain in the 1950s – Tate Britain – 4th January, 2019 – ****

One of my favourite periods. At the intersection of figuration and abstraction. The curators showing the anxieties that plagued society and Western art in the aftermath of the horror of WWII and with the Cold War hanging over it. New materials and processes combined to create sculpture both brutal and beautiful. Some real heavyweights here. Henry Moore, Jacob Epstein, Elizabeth Frink, Eduardo Paolozzi, Reg Butler, William Turnbull. alongside lesser known names for me such as Kenneth Armitage, Bernard Meadows, FE McWilliam, Geoffrey Clarke, Louise Hutchinson and Luciano Minguzzi. And a reminder that Lynn Chadwick was a genius. And how influential this generation was across the world.

Lorenzo Lotto Portraits – National Gallery – 10th January, 2019 – ****

Lotto (1480-1556/7) may have have been lumped in with the Venetians but he got about a bit depending on who commissioned and paid him (Treviso, Marches, Rome, Bergamo, Ancona, Loreto). High Renaissance, never Mannerist but his portraiture evolved through time. Influenced by Giovanni Bellini, early portraits followed the classicism of Giorgione, then the psychological insight comparable with Antonello de Messina, later on more dramatic like Corregio. Forgotten then rediscovered at the end of the C19. Portraits are intense and self aware and often contain clues and insights into the position and status of the subjects. Not a happy chap based on his correspondence. Pointless addition of old stuff similar to items in the portraits for no discernible reason other than padding out the 30 paintings.

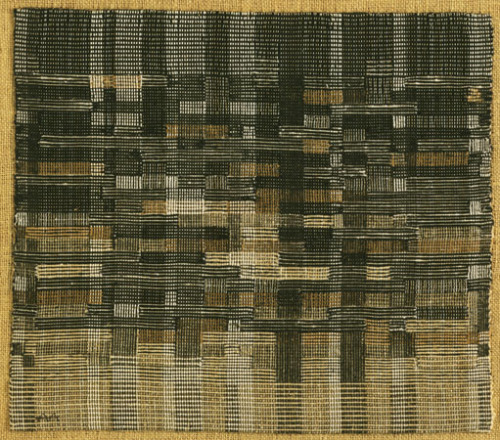

Anni Albers – Tate Modern – 17th January 2019 – ****

Anni Albers combined the craft of hand-weaving with minimalist abstraction. Student at Bauhaus school but discouraged from “fine art” classes so took up weaving. Influenced by Paul Klee and husband Josef Albers. Both educators. Forced out of Nazi Germany. Ended up at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Influence on Op Art and Abstract Expressionists. Small scale pictorial weavings, large wall hangings, textiles, prints drawings. Studied and inspired by ancient art and technique and folk weaving. “On Weaving” 1965. Different materials, textures, weaves, threads, colours, geometries.

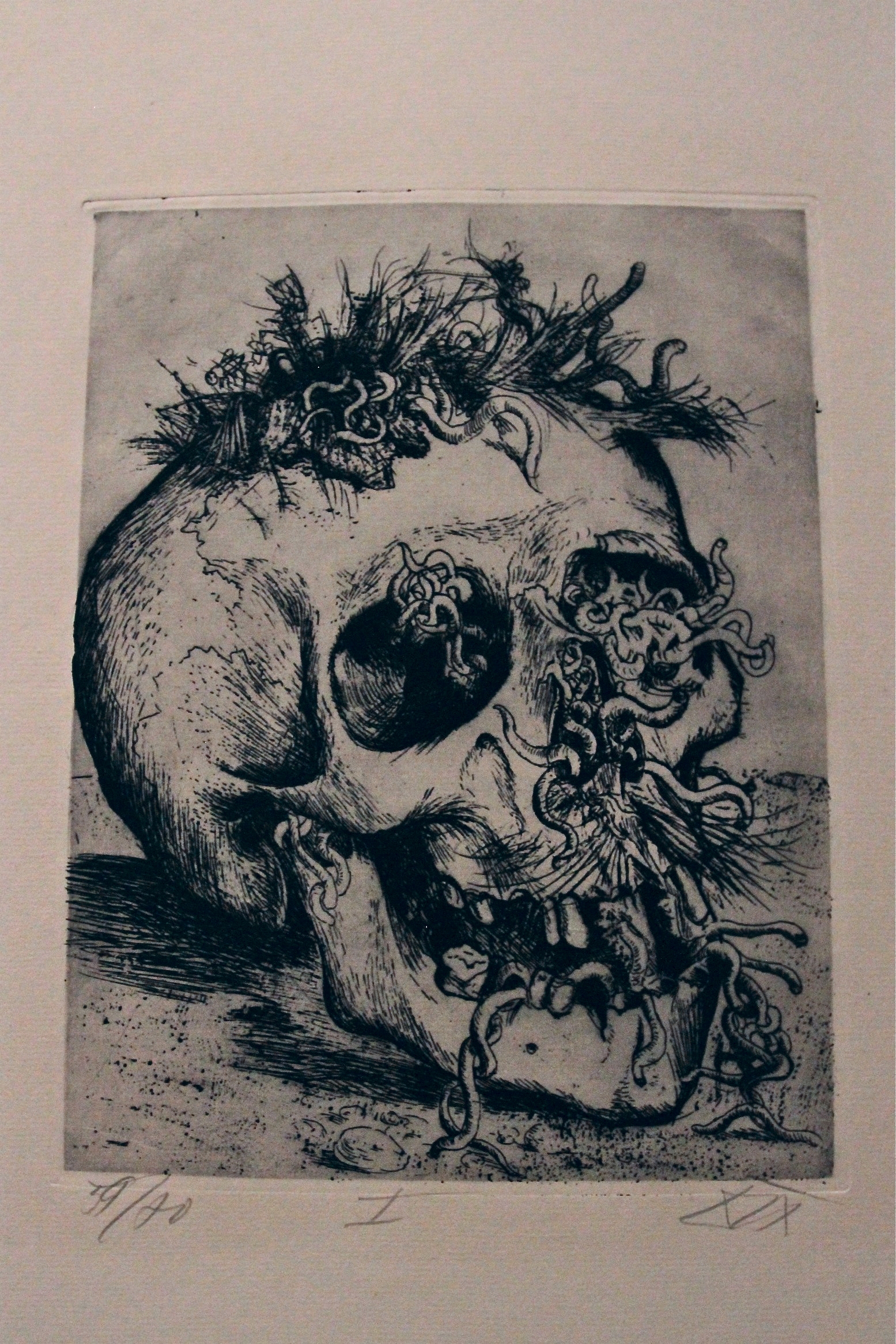

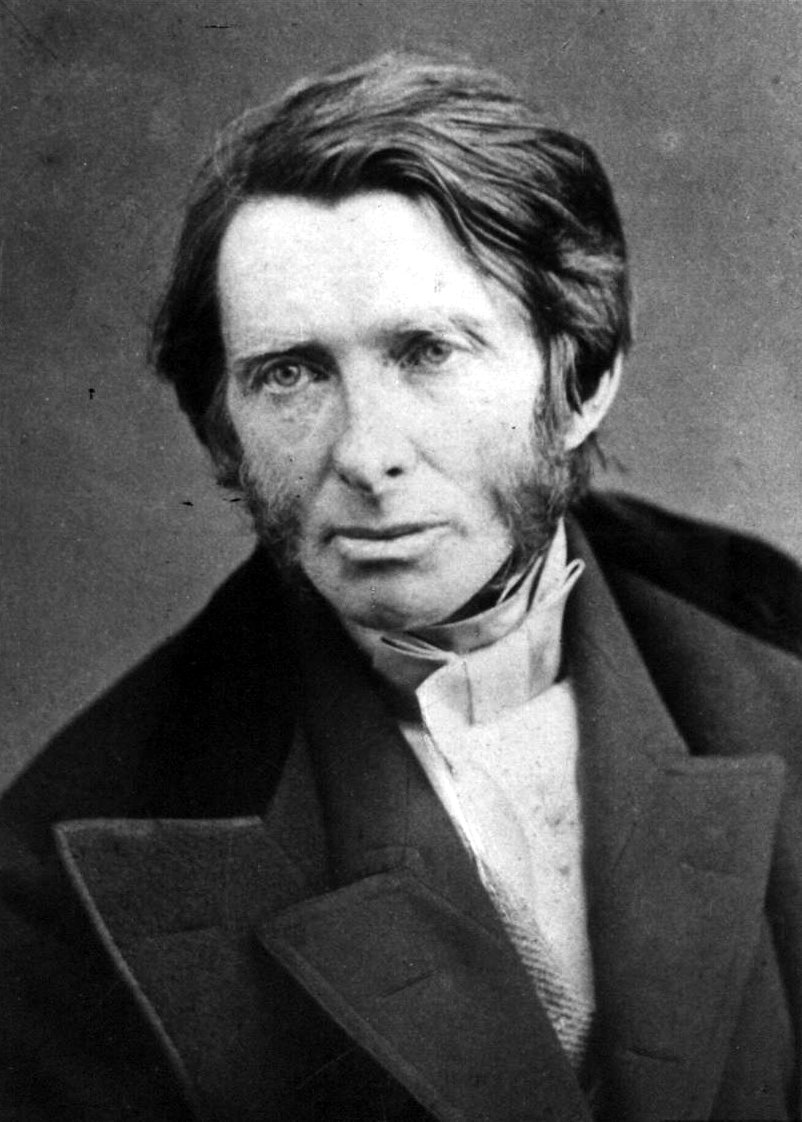

John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing – Two Temple Place – 13th February 2019 – ***

Artist, art critic, educator, social thinker. (1819-1900). In conjunction with Museums of Sheffield which Ruskin created for the people. 190 paintings, drawings, daguerreotypes, metal work, and plaster casts to illustrate how Ruskin’s attitude to aesthetic beauty shaped his radical views on culture and society. Last 25 years retreated into mental illness. Medieval Gothic as inspiration for communal enterprise, makers, guilds, not capitalist production. Detailed, precise drawings and watercolours of nature. Venetian architecture. Landscapes. Collections of objects. Contrast with his religious faith. Influence on Neo-Gothic, architecture, pre-Raphaelites, Arts and Crafts.

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory – Tate Modern – 14th March 2019 – ***

1867 to 1947. Bold use of colour though thin not vibrant. Member of Post-impressionist group Les Nabis. Early work influenced by Gaugin and Japanese prints. Shift into modernism. Landscapes, townscapes, portraits, domestic scenes. Popster designs, lithographs and illustrations. Odd angles, cropping and viewpoints. Martha de Meligny was model who became his wife. Always distinct use of colour, small marks, not from life, used photos and note in studio. Intimate, transient subjects. Overworked and sometimes twee or dull.

Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light – National Gallery – 28th March, 2019 – ****

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923). First UK exhibition of Spain’s leading Impressionist in over a century. Known as the ‘master of light’ for his iridescent canvases. 58 works. Seascapes, garden views, beach bather scenes, portraits, landscapes and genre scenes of Spanish life. Very popular in his day, native of Valencia. Child prodigy, worked quickly, excellent draughtsman. Very striking and lovely paint but no real substance and same techniques and effects across the works. Period when he did examine social issues and contemporary cause celebres (Another Marguerite!) however but these are more moral instruction akin to Dickens in paint. Scenes of rural Spain commission for NYC Hispanic Society. Influence of Singer Sargent and back to Goya and Velasquez. The paint equivalent of a very sweet tooth. Lovely but you can have too much in one sitting. The sunlight is exquisite though. Beach scenes, Sewing the Sail and Raisin Factory stood out. Spanish Art moved up and on with Picasso and Dali but Sorolla still very popular in Spain.

Right I feel better for making those notes. A smidgen of understanding for all those poor youngsters about to take exams and revising like billy-o. Just like LD is right now.