London Symphony Orchestra, Gianandrea Noseda, Nikolai Lugansky (piano)

Barbican Hall, 8th April 2018

- Beethoven – Piano Concerto No 4 in G major, Op 58

- Shostakovich – Symphony No 8 in C minor, Op 65

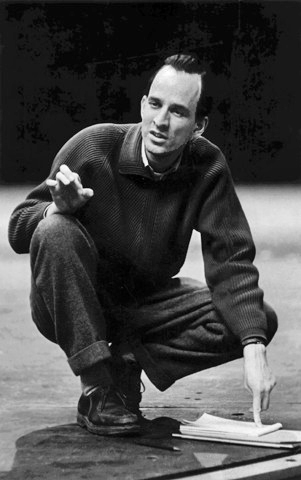

I could be imagining it but the LSO seems to be notching up a gear, from its already high level, each time I hear it. You would never get to hear Shostakovich under Sir Simon Rattle’s baton but here we had one of their two Principal Guest Conductors, in the shape of the inestimable Gianandrea Noseda, tackling DSCH’s mighty gloom-fest No 8, and delivering as good a rendition as you are likely to hear. In recent years, if I wanted to hear convincing performances of DSCH symphonies I would probably look elsewhere, to the LPO and Vladimir Jurowski maybe, though the last time I heard them take on No 8, at the Proms in 2015, it wasn’t perfect.

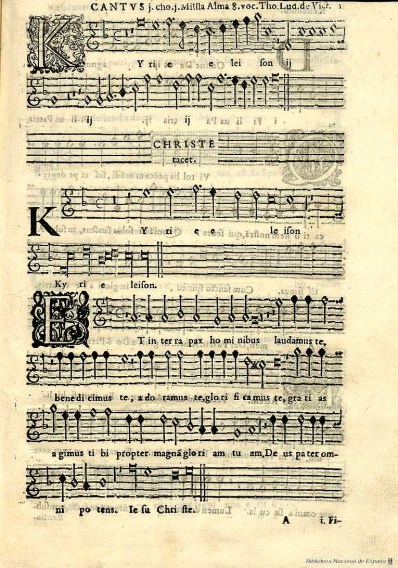

It is all about nailing that epic first movement. I say movement but let’s be honest it is pretty much a symphony in itself. Weighing in at a few minutes short of half an hour, depending on tempi, it winds up, through marches, to an immense tutti, strings blazing, drums rolling, and most of the woodwind and brass involved, before subsiding back to the immense adagio recapitulation of the second theme, with woodwind solos, that DSCH excelled at and which seem to cross all 11 of Russia’s time zones. And, it the conductor and orchestra aren’t careful to establish the line, it can feel like several hours. The tunes themselves aren’t complicated, the key “fate” motif is laid out right at the start, before the two lyrical themes are developed, and it is the fate motif to which orchestra returns before the fabulous cor anglais solo. Time for the LSO’s Christine Pendrill to shine which she did. Her woodwind colleagues also get there time in the sun in the later movements, notably the picccolo of Patricia Moynihan, the bassoon of Rachel Gough and the bass clarinet of Renaud Guy-Rousseau.

Having come out the other end of this movement. DSCH then slaps you, first with one of his textbook sardonic, militarised marches, and then with a moto perpetuo with screams that reeks of the battlefield, (think planes buzzing overhead) and contains the second of the symphonies massive tutti climaxes. The following slow passacaglia movement reworks the fate motif through brass, strings and, memorably, into the bass, before we get some relief in the concluding C major rondo kicked off by the bassoon solo. Even here though we get a repeat of the howling tutti before bass clarinet takes us to some sort of rest with alternate pizzicato and sustaining high strings (the fate motif inverted). As in the first movement, this final allegretto has plenty of action for snare and bass drums and trumpet calls.

DSCH claimed the symphony was, overall, uplifting and life affirming, pointing to the brighter, dancey, folk rhythms in that finale. He must have been taking the p*ss, as so often, given the extreme violence and suffering which characterises the previous movements. This was written over 10 weeks in 1943. Those punters who were expecting a sequel to the story of patriotic resistance apparently laid out in its predecessor, the Leningrad, were sorely disappointed. The Nazis were on the back foot now in Russia but, in retrospect, Dmitry was never going to big up Stalin and the leadership for saving Mother Russia. Its ambiguities are barely concealed, and, when DSCH was once again pilloried for his pessimism in 1948, it was singled out for special criticism.

Yet, for me, all of these middle symphonies wrestle with the same dilemmas. They are just music, so we must be careful not to get sucked too far into the “what did DSCH really mean” cottage industry, but, if we accept that context had an impact then it seems right to believe, that these symphonies, warts and all, are warnings against the depths to which humanity can sink whatever the ideological backdrop. This is not a symphony to set alongside other C minor tragedy to triumph belters, Beethoven 5, Mahler 2, Bruckner 8, it is too brutal overall and the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t bright enough, even with the ocassional tender passages, but I do think it is DCSH’s best, alongside 5 and 10.

Mr Noseda and the LSO are engaged in recording a DSCH symphony cycle. Not sure if this will form part of it but it would be a fitting contribution, assuming the engineers master the Barbican sound. My benchmark recording, as it so often is, is from the maestro Haitink with the Concertgebouw. This performance matched it.

I am afraid I wasn’t as convinced by Nikolai Lugansky’s rendering of Beethoven Fourth Piano Concerto. Mr Lugansky is highly regarded, seen as sympathetic to the music and unshowy, but he is keen on his tinkly rubato, whereas I like my Beethoven direct and muscular. This was too Romantic and insufficiently Classical if you take my meaning. Noseda and the LSO offered up a perfectly apposite support, especially in the strings, but yielded too much to the piano in the second movement, and especially, concluding in the rondo, so it all went a bit arpeggio crazy. Mr Lugansky encored with some Mendelssohn which didn’t help my mood

Still it’s Beethoven and it wasn’t that annoying. And given the quality of the Shostakovich it was a minor irritant. Gianandrea Noseda and the LSO tackle No 10 next. My favourite. Can’t wait.