Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys

Courtauld Gallery, 31st October 2017

I am afraid that the joys of Soutine’s paintings have passed me by in the past. I could see the vibrant colours and intense animation but all that skew-whiffedness left me a bit bewildered. On my last visit to the Musee de L’Orangerie (sorry for sounding like a pretentious twat) I could see there there was something from the extensive Soutine collection in the Jean Walter-Paul Guillaume Collection, but I got captured by the Cezannes. Easily done.

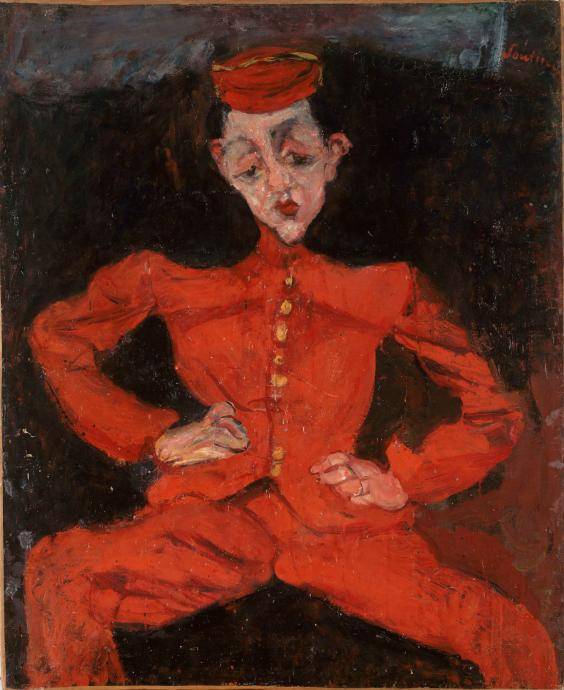

Anyway turns out I should have looked harder. Which is normally the solution to any art appreciation headache. This collection of Soutine’s portraits of various subjects from the French hospitality industry of the 1920’s turns out to be a brilliant introduction to Soutine’s faculties. These people are, with some notable exceptions, bursting with attitude. Painted head on, legs splayed, arms out, eyes staring right back at you, they seem to be willing you for a fight. It is almost as if they would be doing you a favour by “serving” you. Or, in private, they regard you as beneath their contempt. I appreciate that this sounds suspiciously like the stereotype of the disdainful French waiter but it is, nonetheless, plainly there in the canvases, especially in the, ahem, portraits of the waiters, the bell-hops, the valets and even the young page boys. Anyone oik like me who has ever felt intimidated in a fancy dan restaurant or hotel will recognise the look. There are five paintings hung together of the same subject in different guises, playing different roles and with very different moods. Same bloke with a high forehead, red hair, broken nose, but let’s just say he exhibits various degrees of approachability. A bit like you or me on any given work day.

The chefs give off a different vibe. Here you can see, and almost smell, their craft. Even the pastry chefs seem to have an air of meat about them. There is a post WWI Butcher Boy drowned in red but all the Chef’s whites have a reddish hue or flecks. This is where the influence of Soutine on Francis Bacon is most acute. Bacon normally screams carcasse at every opportunity but it seems old Soutine had a similar fascination for the flesh, what with his homages to Chardin’s still lifes and with the rotting joint he stuck up in his flat to the evident annoyance of his neighbours.

The chambermaids are altogether different. Arms down, hands cupped, meek expressions. I can’t really find anything about Soutine’s sexuality but it looks like his eye was drawn to submissive women and saucy boys based on these portraits. These women have more similarity with the elongated simplicity of his mate and fellow Jewish emigre in Paris Modigliani, and as the catalogue points up, even the ethereal women that the genius Gwen John contrived.

Across the whole exhibition, (just 20 paintings in two rooms so no need to work up a sweat, and the Courtauld, as any fool knows, is the most life-affirming space in Central London), the debt to masters such as Rembrandt and Courbet, and colour master Fouquet from an earlier time, is clear. Soutine painted precisely what he saw. This took time but the resulting effect is that he didn’t hang about when he finally saw what he wanted. Hang dog eyes, misshapen ears, pouty lips, chins, foreheads, pointy limbs, whatever leapt out at him, leaps out at us. And all that sticky, oily colour. Vibrant but not in the cartoonish way of some of the German expressionists, but earthy, fleshy, silky. Just like say your man Rembrandt.

Soutine was an outcast in some ways as a Russian emigre, whose Jewishness meant he had to abandon Paris in both wars. Fortunately he made a few quid in his later life but in the end, on the run, he died because he couldn’t get to a hospital quickly enough to treat his stomach ulcer. A small funeral, this was a “degenerate” artist after all, but Picasso pitched up. That tells you something.

His distinctive position as a bridge between the realism of past Masters, and the abstraction of the generation which followed him, took a bit of time to take root despite the acclaim in his lifetime. I would be surprised if his work was everyone’s cup of tea, but if you open your eyes, like I did, I think you might be very pleasantly surprised. Of course no one looks like this but most of us ordinary people look like this.