Rembrandt’s Light

Dulwich Picture Gallery, 17th January 2020

The Tourist has been a bit remiss in keeping up the records on art exhibitions over the last few months so in addition to the above he will offer a few thoughts on other visits.

Rembrandt‘s Light first. The DPG exhibition space is bijou. Just four rooms. Which means you have to time your visit to get a good look. Left this late in the run but not too late but was still worried it might be busy. No need to worry. Late in the day worked.

It’s Rembrandt. With a twist as the rooms imagine the kind of light that the old, (and young with plenty of early/mid work on show,) boy was trying to capture. Like some sort of modern designer/cinematographer. Hence the drafting in of one Peter Suschitzy, a cinematographer on shite like Star Wars to light the show. Daft idea no? Still doesn’t matter. It’s Rembrandt. And by cobbling together loans from the great Rembrandt collections, including the likes of the Louvre and the Rijksmuseum, these 35 often still breathtaking paintings, and a fair few drawings and prints, show just what RHvR could create from one light source and often simple subjects.

So if you ignore all the stupid effects and dispense with an audio guide, (why do I need to listen to someone chirruping on when I should be looking and seeing, information can come later, or before), you’ll be reet. No need to filter these marvels through contemporary reception. If a punter wants to turn art into a flat, lifeless, colourless thumbprint on a phone let ’em I say. Though why they feel the need is a mystery to me. But if you want the hair-raising thrill of imaging just how RHvR fight multiple ways to shine a light on darkness, metaphorically as well as figuratively, then stand and stare.

The portraits at the end, (though I was floored by the Portrait of Catrina Hooghsaet from a private collection – lucky bastard), some of which will be very familiar to Londoners, and the earlier works (and School of) are a little less diverting. However the core of the exhibition, either side of the fake candlelight octagon, (and excluding the mess the concept made of Christ and Mary Magdalene at the Tomb from the Queen’s collection), play a blinder, largely with more intimate works than the blockbusters left at home in Amsterdam. The Flight into Egypt (see above), The Denial of St Peter, The Presentation in the Temple, the studio room etchings and drawings, many just student exercises, Philomen and Baucis, The Entombment, present drama where the biblical sources barely matter. Who’s that there lurking in the darkness? What’s going on in their minds? What happens next?

But mostly you wonder how this complicated man could churn out this sublime stuff for money and why pretty much no-one frankly has been able to match him since.

What else then? In reverse order.

The Bridget Riley retrospective (****) at the over-lit Hayward gallery was proof that less is more when it comes to the impact of the work of the eye-boggling Op Art pioneer. I much preferred the early, monochrome dotty and “folding” checkerboard works, recently revisited with the latest, (she is still had at work aged 88), limited colour palette but was also quite partial to the candy stripes and parallelograms. The Goldsmiths student drawings and life studies, and the later, private, portraits, were new to me but the plans and sketches felt like padding. I might have preferred a little more information on the how and why of her work; the response to nature and her lifelong fascination with how we perceive and see, though the debt to Georges Seurat was acknowledged. And maybe a little bit of science: after all experimental neuroscience and psychology now offer explanations for her magic which weren’t really there in the 1960s when she found her practice. Having said that the way she messes with eyes and brain, rightly, continues to delight pretty much any and every punter who encounters her work. Perhaps explaining her popularity; this was her third retrospective in this very space.

Lucien Freud‘s Self-Portraits (****) at the Royal Academy highlighted both the honesty and the cruelty the great painter brought to his depictions of the human form. The early work reveals the egoist presenting a front to the world – plainly this was a geezer who loved himself. The game-changing addition of Cremnitz white to his palette to create the full fat flesh in which he revealed. The room of often disturbing portraits of friends and family where he lurks in the background, often in reflection. Through to the final, famous, aged nude self portrait where finally he turns his unflinching eye truly back on himself. Seems to me he channeled a fair bit of Grandad Sigmund’s nonsensical methods and conclusions into his work. There is confrontation in every painting: artist and subject, subject and observer and, thereby, artist and observer, this latter being the relationship that most intrigues. It seems he wants to exert control over us but ultimately he cannot, in the same way that however hard he looks, (his sittings were notoriously punishing), he cannot truly capture what he sees.

I like to think that Anselm Kiefer would be the life and soul of the party, a witty raconteur, putting everyone at ease. If you are familiar with his work you might see this as optimistic. AK is the artistic conscience of Germany, now 74, but still constantly returning to its past and particularly the horrors of Nazism and the Holocaust. The monumental scale of his works, the materials, straw, ash, clay, lead and shellac, the objects, names, signatures, myths and symbols, the themes of decay and destruction, the absence of humanity, all point to his provocation and engagement with his birth country’s history. And, in this latest exhibition at the White Cube Bermondsey, Superstrings, Runes, The Norns, Gordian Knot (****), apparently the devastation that we have wrought on the earth itself. The blasted landscapes are thick with paints, emulsions, acrylics, oils and, of course, shellac, then overlaid with wire, twigs and branches, as well as metal runes, axes and, another AK constant, burnt books. The vitrines which make up superstrings are full to bursting with coiled tubes overlaid with equations in AK’s trademark script. As scary, as sinister and as insistent as all his previous work.

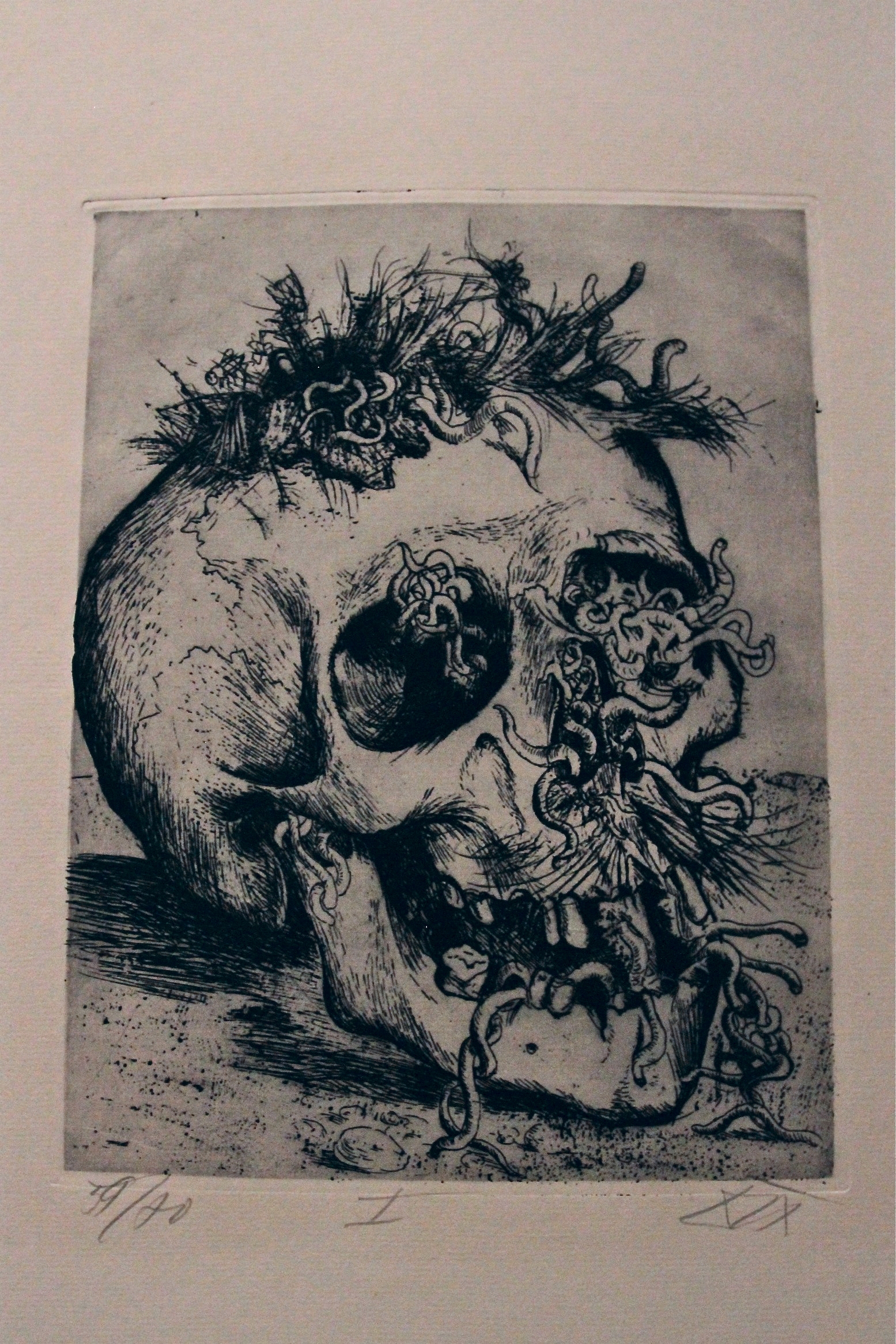

Kathe Kollwitz was an artist who confronted war, as well as poverty and the role of women, not as abstract history but as immediate reality. The small, but perfectly formed, Portrait of an Artist (*****) exhibition at the British Museum (after a UK tour), showcased 48 of her most important prints, woodcuts and lithographs, drawn primarily from the BM archives and elsewhere. Self portraits, premonitions of war, maternal grief, working class protest, all subjects stir powerful emotion but also mastery of line and form.

Elsewhere, Bomberg and the Old Masters at the National Gallery had minimal new to me works on show by IMHO the best British artist of the C20, Leonardo: Experience a Masterpiece at the NG was a joke, I have no idea why anyone would like William Blake‘s (Tate Britain) childish illustrations and Nam June Paik‘s (Tate Modern) admittedly prescient artistic investigation into technology from the 1960s onwards left me nonplussed. The Clash collection of memorabilia at the London Museum was, like so many of these music surveys, just pointless nostalgia.

We (BD and I) didn’t really devote enough time to Olafur Eliasson: In Real Life (****) at Tate Modern, it was pretty busy, but message and invention overwhelm, even if it all feels just a bit too Instagram slick. I dragged the family around Kew Gardens one evening in September last year to see Dale Chihully‘s (****) beautiful organic glass sculpture. I was mightily impressed, SO, BD and LD less so. Bloody annoying traipse around the west end of the park when all the action was concentrated around the Palm House.

Which just leaves the massive Antony Gormley (*****) retrospective at the Royal Academy. I know, I know. There is nothing subtle about AG’s work or “brand” but it is undeniably effective, even if its meanings are often frustratingly unspecific. Coming at the end of an already dark November day, to peer at the utterly flat, and silent, expanse of briney water which filled one room, called Host, was worth the entrance fee alone. It triggers something in collective memory and experience though fuck knows what he is trying to say with it. Same with Iron Baby nestling in the courtyard. Thrusted iron shell men modelled on AG himself, famous from multiple public art installations globally, coming at you from all angles, defying gravity. AG’s body reduced to arrangements of cubes. The imprint in toast. A bunch of rubbish drawings and body imprints. A complex coil of aluminium tube, 8km in total filling one room and a mega-skein of horizontal and vertical steel poles, enclosing, of course, a figure in an empty cube, in another. A metal tunnel that the Tourist was never going to enter in a month of Sundays. Sculpture as engineering to signal an eternal, and inoffensive, spirituality. AG as Everyman. Easy enough to pick holes in but just, er, WOW.