“Master Harold” … and the boys

National Theatre Lyttleton, 26th October 2019

I was surprised by this. Not by the content. Athol Fugard, like his compatriot in the plastic arts William Kentridge, has more than enough inspiration to fuel his art from the history of his nation. Master Harold, like the other plays of his I have seen, therefore deals with the legacy of apartheid. But, being a three hander, with precocious schoolboy Hally whiling away an afternoon at the teahouse owned by his parents in the company of waiter Sam and helper Willie, and most obviously autobiographical, it offers more dramatic dimensionality than the two handers which typify AF’s classic work.

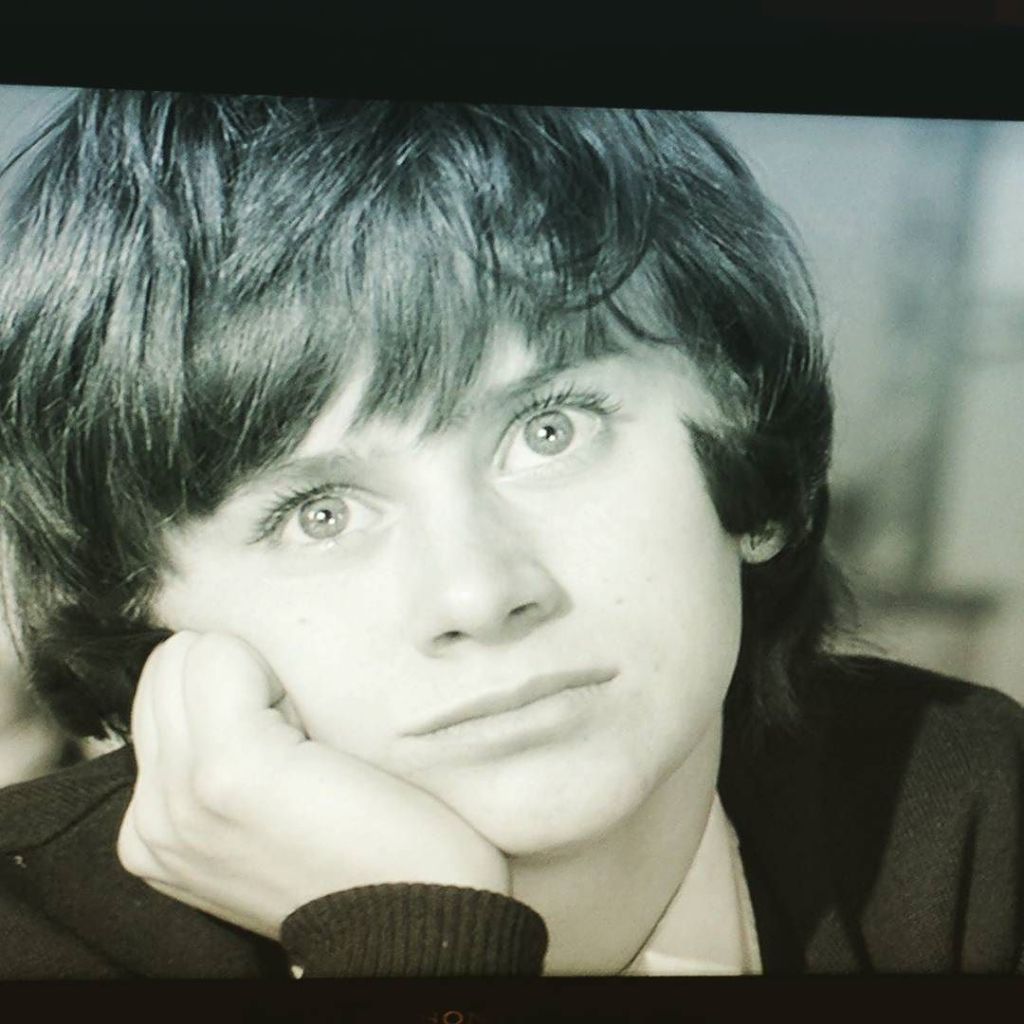

It helps that this is, as far as I can work out, a near perfect production, directed by Roy Alexander Weise, about to take on the joint AD role with Bryony Shanahan at the Royal Exchange Manchester, and responsible for Nine Night and The Mountaintop, (and slated to deliver a revival of Roy Williams’s Sucker Punch at TRSE and an Antigone at the Lyric Hammersmith), on a satisfyingly realistic set courtesy of his regular collaborator Rajha Shakiry. With two actors, Lucien Msamati (Sam) and Hammed Animashaun (Willie) at the top of their games and one, Anson Boon (Hally), who looks like he is poised for great things. Young Anson, with TV series The Feed and Shadowplay, and films, Sulphur and White, The Winter Lake and Sam Mendes’s one take WWI drama, 1917, is about to come to a screen near you, and, on the basis of his performance as Master Harold here, I can see why.

Now I am assuming that a lad from Northampton, who didn’t go to drama school, hasn’t done much in the way of Anglo white middle class South African, specifically Port Elizabeth, mid C20 (1950 to be exact), accents before. With the help of company voice coach Simon Money, and dialect specialist Joel Trill, though he nails it. To be fair this is an exact impersonation of AF’s own voice, winding back seven decades so up an octave, but it is still very convincing. As are the corresponding accents of LM, Sam’s education and knowledge outstripping his position, and HA.

AF’s father was a disabled jazz pianist and his Mum ran a boarding house at tea shop in PE. As well as being a top bloke and brilliant story-teller ,(an essay in the programme tracks his career as an activist and creator of subversive theatre, alongside collaborators Winston Ntshona and John Kani, academic and film-maker), he is also plainly a clever bloke. As, therefore, is the fictional Hally.

On the afternoon of the play Hally’s Mum has gone to visit the alcoholic Dad in hospital and phone calls reveal the strain on the family, with Hally pleading with Mum not to let Dad be discharged. The older Sam (45) is plainly a surrogate father and foil to Hally’s intellectual curiosity with Willie as more of a playful contemporary. Sam and Willie have clearly been looking after Hally for much of his life. The mood is relaxed, with Hally’s patronising attitude, and Sam and Willie’s tolerance thereof, just a given. Willie has asked Sam to help him learn to dance (ballroom crossed cultural divides in SA and here it is a metaphor for life). The conversation between the “friends” flows across a range of subjects. Yet we never forget that Sam and Willie are employees and that the condescending Hally is the “boss”, and eventually, in a fit of pique, Hally loses control and the racial divide is starkly expressed. This pivotal moment, and what follows, even as you guess something is coming, is still very shocking and as powerful a symbol of the stain of apartheid as one could imagine.

The play was banned in South Africa so received its first performances in New York in 1982. Its exposure of the corrosive effect of apartheid, the deflecting subservience of the blacks, the oppressive entitlement of the whites, is all the more affecting because of the lyrical and intellectual nature of AF’s dialogue and the depth of the emotional bonds between the characters. Like all his plays it takes its time, which can weigh down on the drama, and, at first, the writing seems forced, but I think reflects the reality of the complex relationship. It may be that AF has exaggerated the flaws in his autobiographical self, but, as we learn of Hally’s disgust at what caring for his father involves, and his lack of friends his own age, of Willie’s “real” life outside the tea shop as he gets on with the tasks he is set, and we see Sam’s dignity in the face of the everyday injustice that has stunted his life, I think it rings true.