Pericles, Prince de Tyr

Barbican Silk Street Theatre, 19th April 2018

Trust me. You can trust experts. Parading your own ignorance against all the evidence of those who know more than you, just to satisfy your own prejudice, is an ugly human foible. In the very small commercial world of which I was once a part I like to think I knew what I was talking about. When it comes to theatre though I am no expert and you should always seek out the opinions of professional reviewers who do know their onions, as I do. If they think it is very good, it is normally very good, if best avoided, ditto.

In the case of this Cheek by Jowl production though, at their usual London home on Silk Street, it seems that the experts didn’t quite know what to make of it and certainly couldn’t agree. You can safely ignore me, and I recognise I am a pretty easy date theatrically, but I though it was tremendous.

This is the French company affiliate of Declan Donnellan and Nick Ormerod’s Cheek by Jowl empire. There is also a Russian branch. If you want theatre classics, reinterpreted with intelligence, wit and invention, there is no better port of call, (an early Pericles reference for you dear reader), than Cheek by Jowl. But “Shakespeare, in French, in London, what’s that all about Dad, isn’t that too much of a pose even by your standards” to paraphrase LD? Well, it is certainly a different experience, and Shakespeare is about so much more than the words, though I’m not an idiot, I know how important those words are. So a crack ensemble of Gallic thespians, whose previous productions of Ubu Roi and Andromaque did the business, according to them experts, wasn’t to be missed.

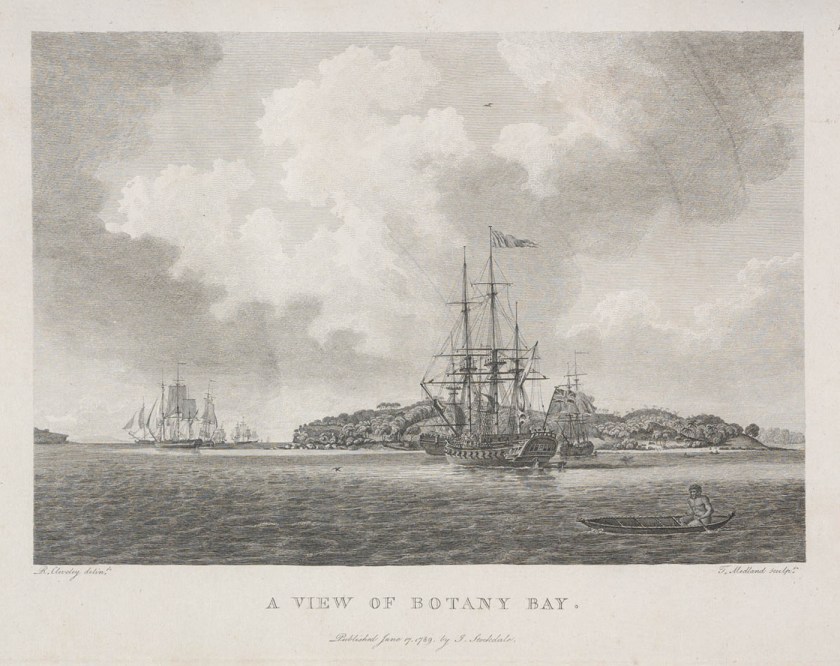

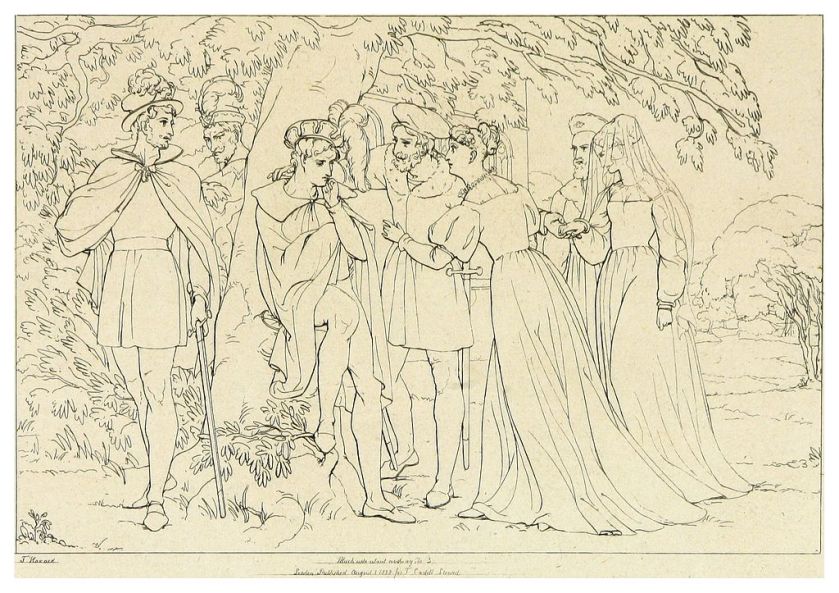

Now Pericles the play, if not the man himself shown above sporting a beard any denizen of Haggerston would be proud of, is a tricky customer. The first couple of acts were written by another bloke, George Wilkins, you can see the join before Will Shakespeare’s acuity becomes apparent, and it really is a rum old plot, written to excite the punters, rather than to make sense. It is a kind of road trip, by sea, of a bloke and his family who keep finding themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time, before it all turns out, improbably, alright in the end. And, as if it wasn’t confusing enough, Messrs Donellan and Ormerod have come up with the cunning idea of locating it all in a hospital ward and, therefore, largely in the mind of patient Pericles.

Apparently they are not the first to come up with this wheeze, but, for me, it was a triumph. They have taken a scalpel to the play’s wilder linguistic excesses, which, with the French translation, sur-titled for bumpkins like me, means it gallops through the story in an unbroken 100 minutes. It can take over three hours normally. It will be interesting to see what the NT comes up with in its forthcoming musical production of the play mixing up an amateur and professional cast.

Now with a story this silly you need your wits about you, especially since the seven strong cast each play at least 3 parts, and the helpful narrator, Gower, in the standard text has been cast adrift. This production, more than ever, supports the Tourist’s contention that it is always worth boning up on the synopsis ahead of any Shakespeare viewing, however many times you have seen the play. No need to treat it like GCSE revision, just a quick reminder of the story will suffice. Then you can focus on performance, spectacle, language, emotion, big Will’s uncanny insight into the human condition, or whatever else takes your fancy. Here, because of the lingo, I could savour the non-verbal communication of all the cast, and the way, they shifted character, and the ingenuity of the production as we shifted between the hospital room and the delusions inside our Prince’s head.

The floor and walls of Nick Ormerod’s set are a vivid, turquoise blue, enhanced by Pascal Noel’s understated lighting design. It was similar to the effect conjured up at the Gate in last year’s intriguing The Unknown Island, that too signalling all things oceanic and marine. The room is filled with hospital details, right the way down to the anti-bacterial hand-wash that the actors take advantage of on entry and exit. Always nice to see a production that cares about hygiene. This hospital room is unlike anything you might see in the creaking NHS though, or even a private hospital, being big enough to accommodate all of Pericles’s family as well as the action from all the exotic Mediterranean locations, Antioch, Tyre, Tarsus, Pentapolis, Ephesus and Mytilene.

(Having said that my one experience of the French healthcare system suggests such luxury might be possible. LD broke her arm pony-riding when she was little, the denouement in a holiday from hell. Very disappointing gite, terrible weather, mother in law crocked her back, dead rat in the swimming pool. The SO stayed with our brave little soldier in hospital, but, carless, a taxi was provisioned for me, by said hospital, so that I could visit prior to her being discharged. Unfortunately my idiocy, and criminal lack of French conversation, saw me dropped down in the wrong wing of the well-appointed hospital. Correct room number though. You can imagine the surprise, nay horror, of the poor French woman, in the early stages of labour, when I popped my head round the door. Mortified I make a rapid exit, mumbling my “pardons”. before I eventually found the right wife and patient. In all the confusion though I do remember the generous size of the room my petrified mon nouveau amie occupied).

Back to Pericles. Our hero, played magnificently by Christophe Gregoire, is asleep in his bed with talk radio humming in the background. He has the gaunt and fevered look of a man prone to psychotic episodes, probably enhanced by powerful medication. The doctor, played by Cecile Leterme, similarly impressive, is doing her rounds. Wife, daughter and friend are watching over him. Cue the first dream/delusion as we kick off with Antiochus (Xavier Boffier) and his rubbish riddle confessing to incest. Like I say you can check out the rest of your story but given that M. Gregoire doubles up as the duplicitous Cleon, Governor of Tarsus, who with wife Dionysa, plot to kill Pericles’s daughter Marina, after he has entrusted her to their care, you need to be on your mettle. He also ends up as the Master of the brothel that Marina escapes to. Meanwhile Mme Leterme, goes one role further, playing the physician, obviously, Cerimon, who revives the half-dead Thaisa, Pericles’s wife, who, he has agreed, should be chucked overboard during shipwreck number two (you read that right). She also plays Simonide, King of Pentapolis and Dad to Thaisa, whose hand Pericles wins through martial derring-do. Oh and goddess Diana, whose temple Thaisa retreats to when she thinks hubby is dead and daughter was never born.

All up to speed. Well Xavier Boffett, also plays Lysimaque, the Governor of Mytilene, brothel town remember, (of which he is a regular patron until swerved by Marina’s saintly virtue), and who brings father and daughter back together at the end. As well as the servant to the Master of the brothel and to bad Dionysa. Who in turn is played by Camille Cayol, in addition to wife, Thaisa, and the Mistress of the brothel. Valentine Catzeflis, thankfully just plays daughter Marina, and, briefly, Antiiochus’s abused daughter. To round things off Guillaume Pottier and Martin Nikonoff step up as various gentlemen, fishermen and knights, without whom the plot wouldn’t make sense (!!!).

In between the Pericleian adventure scenes, even in their truncated form, we have periods of silence when we are back in the (hospital) room, magic suspended, as well as scenes, where Pericles’s delusions are happening in “reality” as opposed to just in his head. Making all of this hang together is an act of imagination on the part of Declan Donellan which rivals that of George Wilkins and William Shakespeare in the first place.

And, for me, it really works. Obviously you lose the Tempest style fantasy from such an interpretation and location. But remember when this was written (1607/08 is the generally accepted date) the audience’s demand for special effects could be accomplished with a few bits of wood, a bit of glue, some pulleys, candles and distraction. If you are going to take a modern, hard-bitten audience, used to films, games and even funny helmets, where technology can conjure up any universe you like, on a believable stage version of Pericles’s journey, you’ll have your work cut out. Look at the technological lengths the RSC went to last year with its holographic Ariel in the Tempest to drag in the kids.

Even if this production eschewed such a journey there was still buckets of theatre-craft, and magic, on show, but it came from the ingenuity of matching the “action” in the play to the setting. The first storm kicks off with Pericles pouring a bed-pan over his head for example, not the only laugh here. The tournament where Pericles wins the hand of Thaisa is conveyed in the corridor behind the room as the orderlies try to pin down Pericles who has gone properly bat-shit. Thaisa’s revival sees her emerging from a body bag on a hospital trolley having been rushed off stage previously in childbirth.

This doesn’t make a lot of sense which ever way you look at it, so why not, literally, make it a dream play, or more exactly a succession of dream plays. And then wait for this supremely talented cast rise to the challenge of condensing character and plot into the transitions the concept afforded. The most powerful scene, and the one all this misadventure builds up to, is the reunion of father, daughter and wife, and I thought it was terrifically moving. If our patient Pericles thinks he is going to die, as it seems here, and therefore lose his family, then the parallels with our Prince Pericles, similarly imperilled, do, sort of, make sense.

Like I say, this may not be for everyone, and is a long way from what you might call, classic Pericles. Then again it is seldom performed probably because, a bit like Cymbeline, it is pretty daft and tricky to swallow. Hidden within, actually not really hidden, the byzantine, travelogue, plot, the stock scenes, the potential coups des theatre, and despite the mangling of Mr Wilkins at the outset, who is more concerned with soapy plot turns that character development, there is some balls out Shakespeare which properly entertains and moves. With a play this highly stylised why not overlay with one more layer of stylisation in an attempt to create a consistent narrative thread.

There is at least one person who cannot wait for next visit from Cheek by Jowl, in whatever language.