Greek

Grimeborn, Arcola Theatre, 13th August 2018

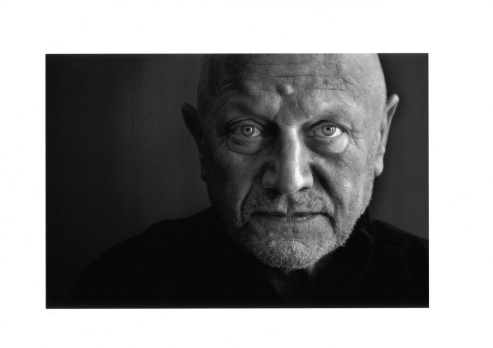

It is a shame Steven Berkoff’s plays don’t get performed more often. They do, like the stage, film and TV villains he has memorably played, (there he is above doing the menacing thing), sometimes lapse into “in yer face” cliche, but at their best they are thrilling theatre. The verse plays, notably East, West and Decadence, are the most exciting, and Greek, which transports Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex to East End London in the 1980s, was inspired. A few nips and tucks to make it fit but moreorless the same brilliant story. I love it, see here for the latest incarnation (Oedipus at Amsterdam Stadsschouwburg review ****). Aristotle thought it was the greatest story ever told and he, being the cleverest bloke that ever lived, knew a thing or two.

More inspired still though was when young Essex lad. Mark-Anthony Turnage, just 28, announced himself to the world with an opera version of Berkoff’s already “musical” play. His mentor Hans Werner Henze suggested the Munich Biennale commission him, and Jonathan Moore helped him with the libretto and directed the premiere. And Mr Moore, no less, was back to direct this production. I was lucky enough to see the first revival in 1990 at the ENO and, I tell you, it blew my socks off. I knew it was possible for opera to be the best of art forms when I was a young’un but I had also been disappointed by some allegedly top notch productions of classics by the likes of Verdi, Puccini and, even, God forgive me, Wagner. I was bored witless by much of this nonsense. But Greek, as one of the first contemporary operas I saw, made me realise that it is the theatre that matters and not the singing. Not saying that when the singing, music and drama all come together I can’t be moved by “classic” opera, especially Mozart and Monteverdi, just that it is a lot easier when the stories stack up and mean something to me and the music isn’t just a bunch of whistling tunes all loosely stitched together.

Of course some buffs might not accept that Greek is an opera at all, more musical theatre in the manner of Brecht and Weill at their best. I see their point. Indeed M-AT, probably more to wind us all up, termed it an anti-opera. Anyway who cares. Greek was a punch in the gut and food for the brain first time round for sure. Mr Turnage, with his rock and jazz inflections, and his adoration of Stravinsky especially, and the likes of Britten and Berg, as well as teacher Oliver Knussen, knows how to compose for the theatre. I knew nothing about the source of his latest outing Coraline (Coraline at the Barbican Theatre review ****) so had no baggage and, whilst if might not be up to Greek and to his version of The Silver Tassie, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

No need to trot you through the story here in detail I assume. By having the lead, here named Eddie, living a life of frustration in Thatcher’s Britain, Berkoff and Turnage have a contemporary alternative for the plague afflicting Thebes. Mr Moore wisely sticks with the 1980s, no need to invoke “Austerity/Brexit” Britain, that would be crass, which designer Baska Wesolowska, through set and multiple costume changes, neatly evokes. Class relations, cultural impoverishment, addiction, the patriarchy, hopelessness are all revealed but never bog down the story.

The differences between “foundling” Eddy and his heavy drinking Mum and Dad, and Sister, are highlighted by their over the top, “gor-blimey, Eastender, chav, working class” dialogue (no arias here folks) and movements. Eddy is angry and frustrated with them so, after having his fortune told, understandably f*cks off to meet, then marry Wife/real Mum, after an ill-fated altercation with her first hubby in a caff. There’s a fair bit of cursing and violence and the still marvellous riot, Sphinx and “mad” scenes, where M-AT’s brilliantly percussive score is at its best. It is funny and aggressive by turns, is deliberately cartoonish, has some great tunes and musical, (and music-hall), echoes and it belts through the story. And there’s a twist as you might have guessed.

Edmund Danon was a perfect Eddy if you ask me. M-AT asks for a high baritone and that is what Mr Danon provides. Every word was clear as a bell and boy did he get round the Arcola space. As did baritone Richard Morrison as Dad (as well as the, in so many ways, unfortunate Cafe owner and the Police Chief). For choice I preferred the mezzo voice of Laura Woods as Wife, as well as sister Doreen, Sphinx I and Waitress I, over the purer soprano of Philippa Boyle as Mum, Sphinx II and Waitress II.

Greek is now a staple of the operatic circuit as it can reliably pull in younger punters to even the grandest of opera houses, (the ROH got on the bandwagon in 2011). Its physicality, irreverence, punky aesthetic and social commentary can appear a little quaint now, especially if it is “over-produced” in a big space. Which, once again shows why Grimeborn, and the Arcola, is the perfect setting for works like this. With the Kantanti Ensemble, founded by conductor Lee Reynolds to showcase the best young musicians in the South East, under the baton of Tim Anderson, by turns belting out, and reining in, the score, the toes of the audience at risk of crushing from the four performers bounding around the Arcola main stage, and with the original director in charge, this production stripped Greek back to where is should be. Another Grimeborn triumph.

I genuinely urge you to try and see this once in your life. Especially if you think opera is for w*ankers. You will be blown away without any need to reassess that, largely reasonable, preconception.