The Antipodes

National Theatre Dorfman, 23rd November 2019

I’ll tell you what. That Annie Baker backs herself. Here is another long play, near 2 hours straight through, where, visually, nothing much happens, bar a properly weird interlude, and dense with word. And this time it is a story about stories, Yep that’s right. The meta of meta. Six assorted punters (five men and just one woman) are ranged around a glass, conference style table telling each other stories in an attempt to create a story. Mediated by their distracted passive aggressive boss Sandy (the ever wonderful Conleth Hill), with occasional interruptions from his chipper assistant Sarah (Imogen Doel) to take food orders, excuse Sandy’s absences and chivvy the crew, and the voice of mogul “Max” (Andrew Woodall) who is bankrolling the enterprise. And with a note taker, Brian (Bill Milner), who eventually, memorably, gets stuck in.

It looks and feels like a scriptwriter’s meeting but its real purpose is never fully revealed and the rules of engagement are vague. Just see what happens seems to be Sandy’s instruction and from this all sorts of stuff pours out, from personal disclosures and confessionals, jokes, classical myth and allusion, gods, monsters, religious dualism, stories about stories, right through to various creation myths. It is affecting, thoughtful, funny, intriguing. Chloe Lamford’s set, complete with Perrier overload, Natasha Chiver’s garish lighting, Tom Gibbons’s sound, Sasha Milavic Davies’s movement (much use of swivel chairs), all echo the hyper-reality, or do I mean hyper-banality, of Annie Baker’s text, which gradually shifts the apparently mundane into the realms of the extraordinary. No surprise that Ms Lamford and Ms Baker co-direct.

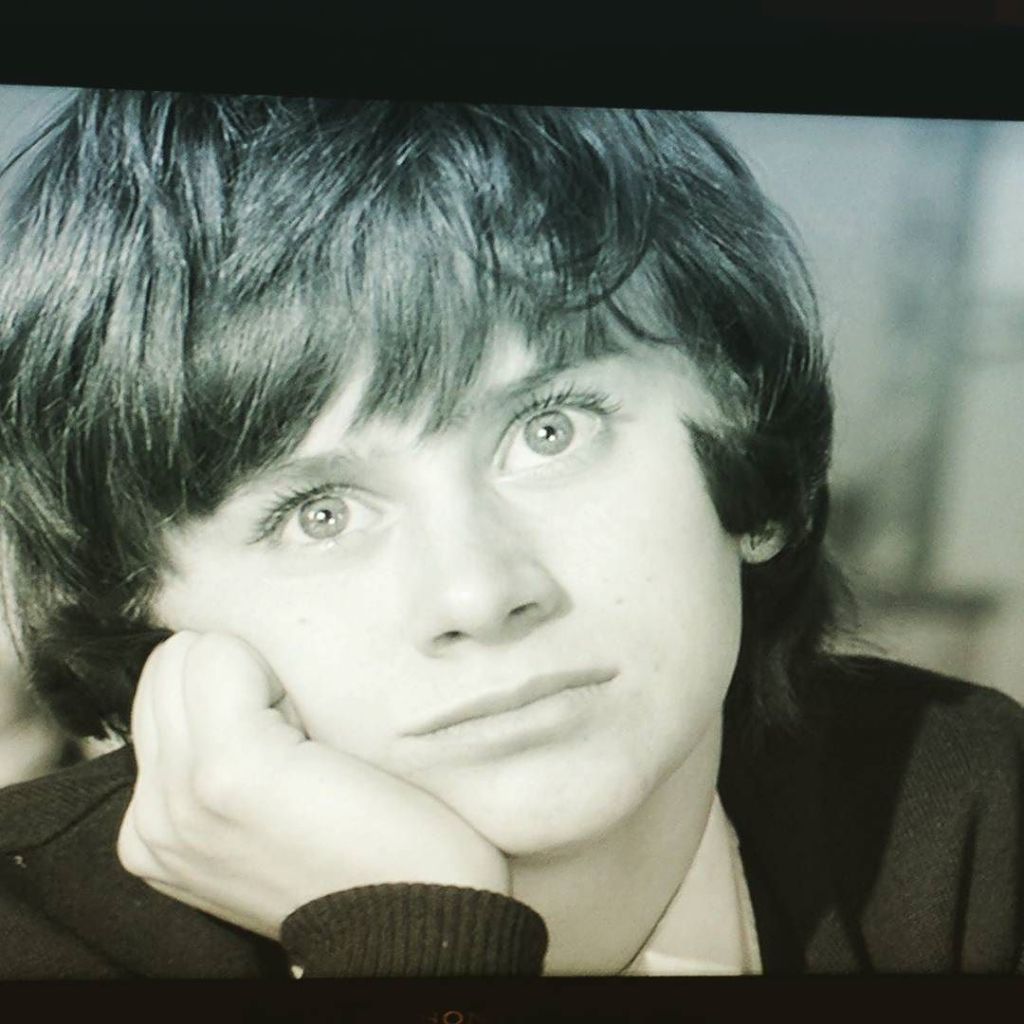

It doesn’t quite scale the heights of profundity that it sets out to achieve, or the genuine grace of predecessor John, and it probably stole 20 minutes of my life more than it should have, but you still couldn’t fault its ambition and verve. In trying our patience, and venturing into the Freudian “uncanny”, it gets right under your skin even if it doesn’t shed too much fresh light on the creation of collective, and self, narrative. But it does cover all the bases, maybe too many, as concept overwhelms even this committed execution. Though with actors of this quality, Fisayo Akinade, Matt Bardock, Arthur Darvill, Hadley Fraser, Stuart McQuarrie and Sinead Matthews as the writers), individual character emerges out of the ensemble.

I guess the point was that whilst the urge to share our truth and humanity, and bring meaning to pointless existence, through stories remains undimmed, our capacity to do so might be fading, (especially as chaos in the outside world seeped into the ill-judged ending). Or maybe not. The vagueness of purpose is all part of the attraction in Annie Baker’s practice, so best just to go with the intractable flow and don’t pull too hard on the individual, intellectual, threads. It won’t be one of my top 10 2019 theatrical events but was still a story that could not be missed.