Ghosts

Royal and Derngate Theatre Northampton, 2nd May 2019

A little bit of back to back Ibsen action. First this Ghosts and then, a few days later, Rosmersholm at the Duke of York’s. And the Tourist’s first visit to the Royal and Derngate which, he has Benn rather slow to observe, has been producing some very tempting offers as of late. I gather most of the drama here, (plays not fist-fights), takes place in the Royal with the larger Derngate offering a broader range of entertainment (Wet, Wet, Wet on the evening of the afternoon the Tourist attended, for those few of you who might be tempted by such). Both are wrapped inside a fine, open foyer area and I gather there are other spaces as well, the Underground Studio and a Filmhouse. All round very impressive.

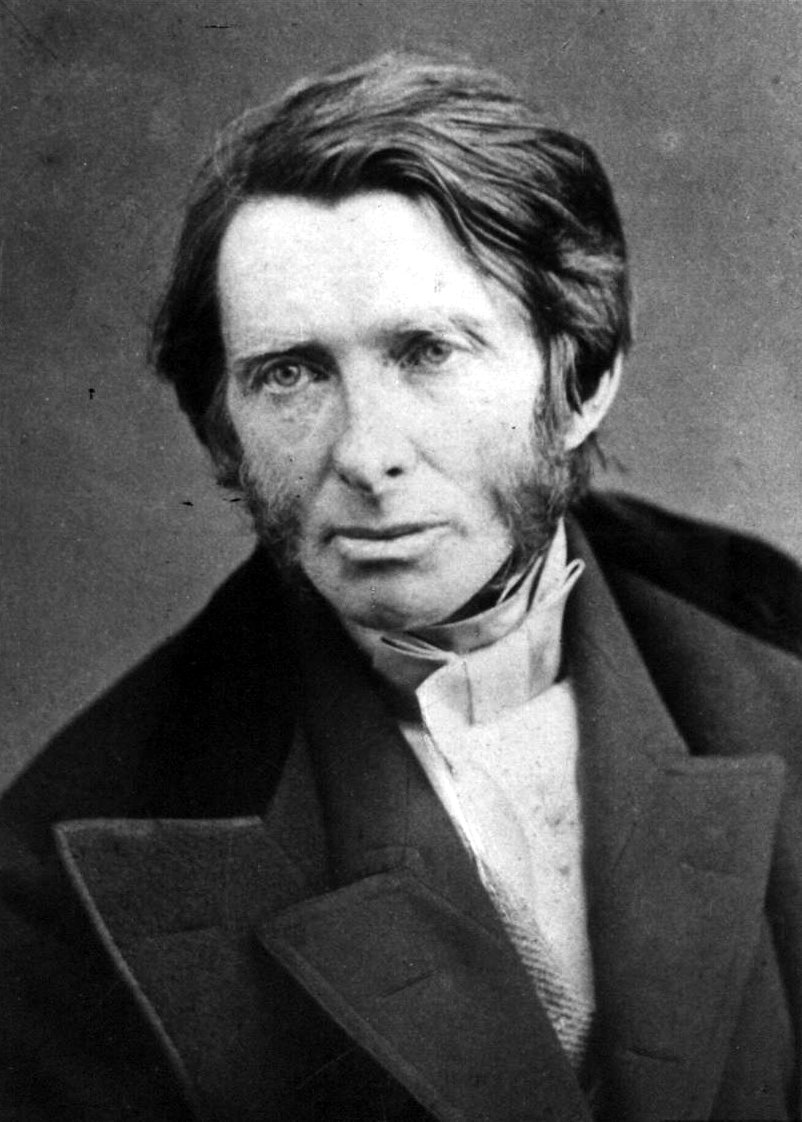

As was this production of Ghosts, masterminded by director Lucy Bailey in a new version from Mike Poulton. Mr Poulton has a long history of adapting the European classics, Chekhov, Schiller, and a definitive version of Turgenev’s Fortune’s Fool. His last outing was the excellent RSC two part Imperium, the story of Cicero, which I caught on its London transfer. I last saw Ghosts in 2013/14, two versions pretty much back to back. In Richard Eyre’s West End take Lesley Manville pretty much wiped the floor with any other Helen Alving’s past and future. In the other, Stephen Unwin’s ETT version at the Rose Kingston (his final play there as AD), well let us just charitably say it didn’t quite match it. But Ghosts is such a fine play in my book that it is hard to go too far wrong.

Having said that it is possible to get bogged down in old Henrik’s miserabilism. Religion, syphilis, potential incest and assisted suicide are never likely to make their way into the repertoire of, say, Mischief Theatre, (though Ghosts: The Musical might prove tempting), but there is more in terms of plot and character beyond a metaphor for late C19 moral hypocrisy. Helen Alving, holed up in her gloomy mansion, is a woman of rare depth, her doomed son Osvald does have moments of joy, at least potentially, Pastor Manders is not entirely devoid of sympathy, Jakob Engstrand wants to atone and Regina will, I think, one day come to terms with her parentage.

Indeed if it wasn’t for the prize c*nt, the dead Captain Alving, things might have been very different. He was the faithless husband who ruins his wife’s, his son’s and Regina’s lives. The sins of the father and all that. (The Danish/Norwegian title is Gengangere, “the thing that walks again”, which is more like a revenant than a ghost, someone and something that comes back to haunt others). By confronting the past Helen knows she is going to make things worse, of course, but this is also, as with all of Ibsen’s important women, a catharsis to break free from that past and to engage with the truth however ugly. To reject the social mores and religious convention that trapped her in the painful marriage, even if it is too late for her son and her dead husband’s illegitimate daughter.

Lucy Bailey, Mike Poulton and designer Mike Britton have worked together before and it shows. Adaptation flows into direction which is perfectly framed by the set. Mr Britton was apparently inspired by Edvard Munch’s art. Munch produced numerous illustrations of Ibsen’s plays and designed a production of the play in 1906 shortly after HI’s death. The darkest of dark blue-greens, think Farrow and Ball Green Smoke but darker, creates a fitting “psychological” backdrop. Gauze screens divide reception rooms and conjure up spectres. Props, costumes and architecture details are spot on period, straight out of a Vilhelm Hammershoi interior (as above). This is what Ibsen should look like. After the effective orphanage fire the set does angle back to create a “pit” which the actors have to clumsily navigate but otherwise this was perfection.

Made more so by Oliver’s Fenwick’s moody lighting and by Richard Hammarton’s sound design and composition. No barely audible ambient background noise here. A proper soundscape. With lots and lots of rain and a proper fire. And some top drawer cello, violin and piano chord dissonance.

It is possible to judge the success of a production of Ghosts as pure drama by the reaction of the uninitiated members of the audience to the various disclosures. Ibsen, being a genius, doesn’t just bounce them out in a line or two of clumsy exposition, they emerge, organically, from the plot. Mr Poulton’s adaptation perfectly registers these twists, not quite turning it into a thriller, that would be asking too much, but definitely more than enough to persuade the Ibsen-curious. Well maybe not all, as I overhead some student-y types complaining it was too “text-y” afterwards. Trust me kids this is as racy as Ibsen gets.

Penny Downie, particularly in the scenes where she rounds on Manders, was a fine, dignified, Helen Alving. Pierro Niel-Mee’s Osvald was a little too camp for my taste. I know he is an artistic type but too much surface petulance risks losing the despair of what might have been. Declan Conlon’s Jakob by contrast was well rounded and Eleanor McLoughlin wisely held back to make her escape at the end more pointed. James Wilby did verge on the shouty at times but his Pastor was sufficiently human, confused, and, finally, ashamed, to make the initial friendship with Helen believable (sometimes a problem if he is overly puritanical).

Apparently Ibsen only took a few weeks to write Ghosts in 1881, whilst summering in Sorrento, though it didn’t get staged until the following year by a Danish company in Chicago. The subject matter was in part a two-fingered riposte to all the churchmen and stiff-necks back home in Norway who got wound up by the his previous play, the far milder A Doll’s House. There his heroine Nora walks out on her sh*t-head husband. Here we see what can happen when a wife is convinced to stay. If HI thought he had wound up his conservative enemies with A Doll’s House, they went batsh*t when Ghosts arrived back home. Even when the King of Sweden loaded up HI with medals and honours galore years later, as he was recognised as Scandi’s greatest cultural export (at least until ABBA, just joking), his maj told him off for writing Ghosts.

HI famously said “we go through life with a corpse on our back”. This masterly version shows just why Ghosts is probably, IMHO, the Ibsen play which best represents this maxim. If our Henrik never stopped picking away at the scabs of his own life and the society around him then Ghosts is when the blood started to properly flow.

I will be back at the R&D. I have seen three of the Made in Northampton shows that are currently touring, Touching the Void, The Remains of the Day and the Headlong Richard III. The first two are outstanding and I see that Touching the Void is coming to London later this year. Mandatory viewing. I missed Our Lady of Kibeho which, judging by the reviews, was a massive oversight. So I am not going to make the same mistake with The Pope, Two Trains Running and A View From The Bridge in the rest of this season.

I can see why the R&D has garnered awards though, and, I say this with the greatest respec,t it is hard to reconcile the fact that its AD, James Dacre, has the ex-editor of the Daily Mail for his dad. It would seem that, in this case, the sins of the father have not been visited on the son.