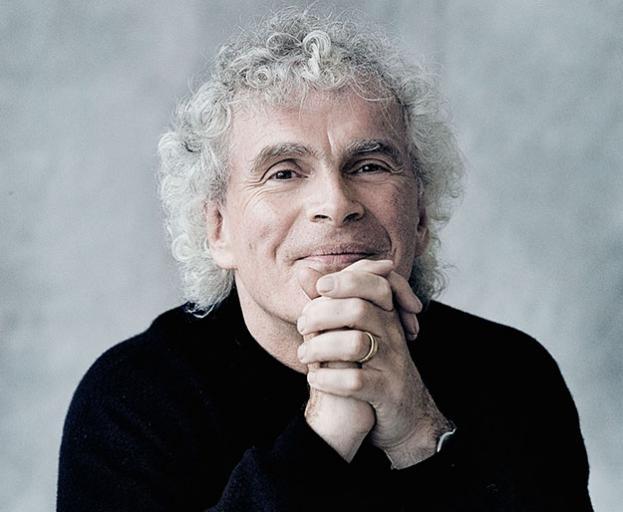

Right I know it is a bit late in the day but I wanted to make a list of the concerts I enjoyed most from last year. So everything that got a 5* review based on my entirely subjective criteria is ordered below. Top is Sir Simon and the LSO with their Stravinsky ballets. Like it was going to be anything else.

Anyway no preamble. No waffle. Barely any punctuation. Part record, part boast. Comments welcome.

- LSO, Simon Rattle – Stravinsky, The Firebird (original ballet), Petrushka (1947 version), The Rite of Spring – Barbican Hall – 24th September

- Colin Currie Group, Synergy Vocals – Reich Tehillim, Drumming – Royal Festival Hall – 5th May

- Isabelle Faust, Akademie fur Alte Musik Berlin, Bernhard Forck – JS Bach Suite No 2 in A Minor BWV 1067a, Violin Concerto in E Major BWV 1042, Violin Concerto in A Minor BWV 1041, Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor BWV 1043, CPE Bach String Symphony in B Minor W 182/5 – Wigmore Hall – 29th June

- Jack Quartet – Iannis Xenakis, Ergma for string quartet, Embellie for solo viola, Mikka ‘S’ for solo violin, Kottos for solo cello, Hunem-Iduhey for violin and cello, ST/4 –1, 080262 for string quartet – Wigmore Hall – 25th February

- Britten Sinfonia, Thomas Ades – Gerald Barry Chevaux de Frise, Beethoven Symphony No 3 in E Flat Major Eroica – Barbican Hall – 6th June 2017

- Nederlands Kamerkoor,Peter Dijkstra – Sacred and Profane – Britten Hymn to St Cecilia, Gabriel Jackson Ave Regina caelorum, Berio Cries of London, Lars Johan Werle Orpheus, Canzone 126 di Francesca Petraraca, Britten Sacred and Profane – Cadogan Hall – 8th March

- Tim Gill cello, Fali Pavri piano, Sound Intermedia – Webern 3 kleine Stücke, Op. 11, Messiaen ‘Louange à l’Éternite du Jesus Christ’ (‘Praise to the eternity of Jesus’) from Quartet for the End of Time, Henze Serenade for solo cello, Arvo Pärt Fratres, Xenakis Kottos for solo cello, Jonathan Harvey Ricercare una melodia for solo cello and electronics, Thomas Ades ‘L’eaux’ from Lieux retrouvés, Anna Clyne Paint Box for cello and tape, Harrison Birtwistle Wie Eine Fuga from Bogenstrich – Kings Place – 6th May

- Britten Sinfonia, Thomas Ades, Mark Stone – Gerald Barry Beethoven, Beethoven Symphonies Nos 1 and 2 – Barbican Hall – 2nd June

- Academy of Ancient Music, Robert Howarth – Monteverdi Vespers 1610 – Barbican Hall – 23rd June

- Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, Murray Perahia – Beethoven Coriolan Overture, Piano Concertos No 2 in B flat major and No 4 in G major – Barbican – 20th February

- London Sinfonietta and students, Lucy Shaufer, Kings Place Choir – Luciano Berio, Lepi Yuro, E si fussi pisci, Duetti: Aldo, Naturale, Duetti: Various, Divertimento, Chamber Music, Sequenza II harp, Autre fois, Lied clarinet, Air, Berceuse for Gyorgy Kurtag, Sequenza I flute, Musica Leggera, O King – Kings Place – 4th November

- Maurizio Pollini – Schoenberg 3 Pieces for piano, Op.11, 6 Little pieces for piano, Op.19, Beethoven, Piano Sonata in C minor, Op.13 (Pathétique), Piano Sonata in F sharp, Op.78 (à Thérèse), Piano Sonata in F minor, Op.57 (Appassionata) – RFH – 14th March

- Britten Sinfonia, Thomas Ades, Gerald Barry – Beethoven Septet Op 20, Piano Trio Op 70/2. Gerald Barry Five Chorales from the Intelligence Park – Milton Court Concert Hall – 30th May

- Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Mariss Jansons, Yefim Bronfman – Beethoven Piano Concerto No 4, Prokofiev Symphony No 5 – Barbican Hall – 24th November

- Britten Sinfonia, Helen Grime – Purcell Fantasia upon one note, Oliver Knussen, George Benjamin, Colin Matthew, A Purcell Garland, Helen Grime Into the Faded Air, A Cold Spring, Knussen Cantata, Ades Court Studies from The Tempest, Britten Sinfonietta, Stravinsky Dumbarton Oaks – Milton Court Hall – 20th September