Los Angeles Master Chorale, Grant Gershon (conductor), Peter Sellars (director)

Barbican Hall, 23rd May 2019

Much taken with our last exposure to Peter Sellars distinctive way with dramatising the choral after the OAE St John Passion at the Festival Hall last month, BUD and I set off, fuelled as usual by an excellent carb repast from Bad Egg, to hear and see this version of Lasso’s masterpiece on the Barbican stage.

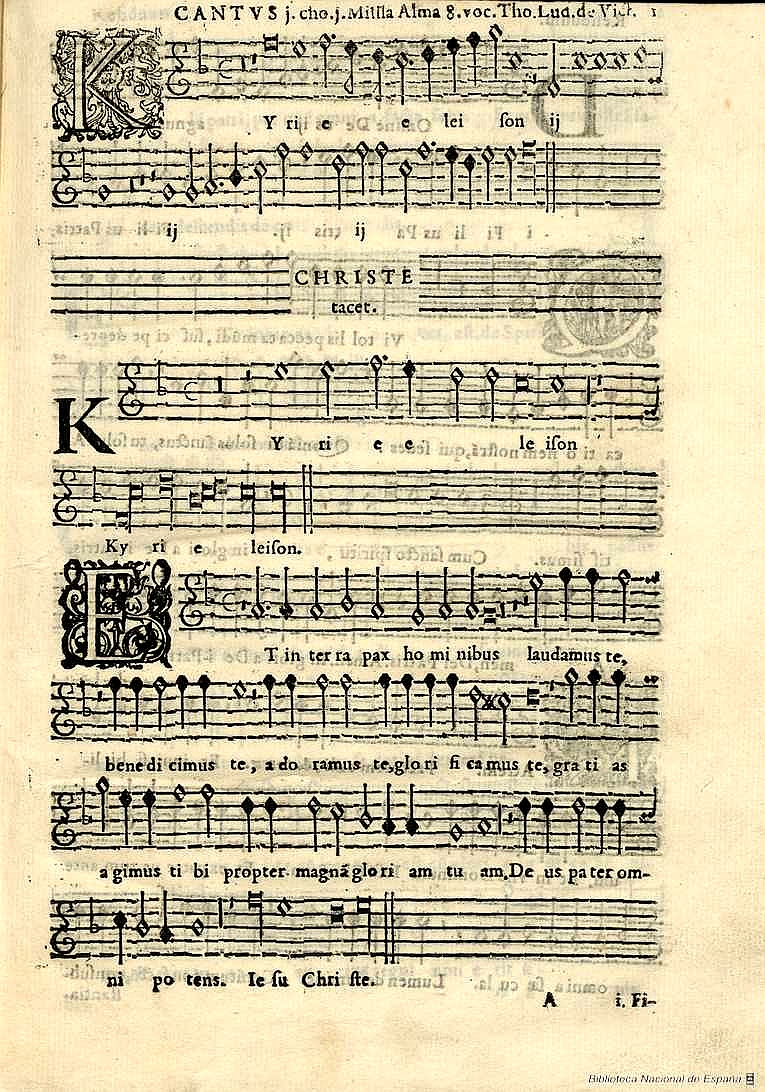

Now this was an altogether different experience from the Bach. (unfortunately I missed Mr Sellars take on Stravinsky with the Philharmonia and Salonen). Orlande de Lassus (or Roland de Lassus, Orlando di Lasso, Orlandus Lassus, Orlande de Lattre or Roland de Lattre, take your pick), was a big noise in late Renaissance polyphony, alongside Palestrina and Victoria, who left his native Flanders at the tender age of twelve to ply his singing and composition trade in Mantua, Sicily, Milan, Naples, Rome, then to France and England, back to Antwerp, on to Munich and the Bavarian Court, where he remained until his death in 1594, albeit with plenty more business trips to Italy. Freedom of movement see, at a time when one bit of Europe was economically and culturally much like another. It works to everyone’s advantage despite what the swivel-eyed Brexit nutters tell you.

In total Lasso wrote over 2,000 vocal works including 60 (mostly parody) masses, passions, psalm settings, 530 motets, 175 Italian madrigals, 150 French chansons and 90 German lieder. No instrumental music remains; though it seems unlikely that a composer this busy and this much in demand would not have turned his hand to non-vocal works. He was just as much at home in bawdy, secular comedy as he was in strictly orthodox liturgy and certainly pushed the limits of polyphony with exotic chromaticism and highly wrought word painting. There he is above. Makes me wonder if it is time for a revival of the gentleman’s ruff to better show off our beards.

His most famous work is this, the work on show at this performance, a penitential cycle of 20 “spiritual madrigals” and a concluding Latin motet, the Lagrime di San Pietro, (The Tears of St Peter), his final work before he died in 1594. It is scored for 7 voices and is divided equally into three sections, (reflecting St Peter’s claim to fame, the thrice-fold denial of Christ, the holy trinity, the seven sorrows of the Virgin Mary, and no doubt much other Christian numerological hokum). In this performance the LA Master Chorale was comprised of 21 voices, 6 “canto” for which read soprano, 6 alto, 6 tenor and 3 bass. The settings use 7 of the 8 “church modes”, the system of pitch organisation on which chant was built, as well as for the final motet the tonus perigrinus, outside of the system to symbolise imperfection, and come from the poems of Luigi Tansillo (1510-1568). It is through composed with no repetition and Lasso uses all of the skills he had developed in his previous works to create the maximum of emotional, (as well as all this symbolic), impact.

You don’t need to know anything about the arcane history of the secular madrigal, nor Renaissance polyphony more generally, nor all this structural mumbo-jumbo, to be moved by the piece. And it is pretty easy to see why Lasso alighted on these texts. And why the LA Master Chorale, (widely recognised, not least in their own blurb, though I have no reason to doubt it after this performance, as the US’s premier vocal ensemble), under conductor Grant Gershon, should have worked so hard to perfect the performance. Nor why Peter Sellars should have alighted on this for his first stage at directing a non-instrumental piece.

It is, thanks to Tansillo’s faintly (actually not so faintly) melodramatic Italian poetry and Lasso’s extraordinary invention, an inherently dramatic piece, even if it isn’t strictly chronological. Bows, arrows, swords, spears, stabs, wounds, tears, pain, sorrow, shame. You get the picture and that’s just the first couple of madrigals. There’s a couple of lighter moments but it’s mostly the usual Christian S&M guilt trip. So much suffering. Mind you I suppose Lasso was staring death in the face so I can see why he didn’t go with “The Sun Has Got His Hat On”.

Mr Sellars wheels out his usual ritual tropes, arm waving and hand gestures which tend towards the literal, lying on the floor, the whole ensemble assembling tableau style into an alarmed or alarming crowd, various combinations of writhing twos and threes. Remove the music and you could be watching a physical theatre acting class or maybe attending an anger management retreat. Costumes from Daniella Domingue Sumi are gym casual monochrome. The lighting design of Jim F Ingalls is similarly unsubtle. There is a faint whiff of 1970s California.

But you know what, it all works. I can see why some of the pukka reviewers were a bit sniffy about the whole affair but for BUD and I, who like a bit of visual stimulus, it hit the spot. Maybe not “visualising the polyphony” as Mr Sellars claims, but certainly telling a non-linear story. What was most extraordinary however was the sound of the LA Master Chorale. Remember they had to commit both score and choreography to memory. Despite all the on stage shuffling their tone throughout was so precise and so smooth, even in the most complex counterpoint, the shifting dissonances and the meanders through to resolutions. Far less austere than when performed by a European ensemble in penguin suits and evening dresses that’s for sure and better for it.

I was idly through some lists of the greatest choral works ever written which, variously, cover the whole gamut from the very earliest organum from Notre Dame to bang up to date contemporary. But surprisingly few of these lists mention this, Lasso’s finest hour, (well 80 minutes ). Which can’t be right.

Here’s my tuppence worth. Usual rules. No particular order. Well sort of chronological. Only one work per composer. Which is tough on old Bach in particular. All blokes. Sorry.

- Perotin – Viderunt omnes

- Josquin des Prez – Missa Pange Lingua

- John Taverner – Mass “The Western Wynde”

- Giovanni Pierluigi de Palestrina – Missa Papae Marcelli

- Thomas Tallis – Lamentations of Jeremiah

- Tomas de Luis Victoria – O magnum mysterium

- Orland de Lassus – Lagrime di San Pietro

- William Byrd – Mass for 5 Voices

- Claudio Monteverdi – Vespers of 1610

- Carlo Gesualdo – Tenebrae Responsories

- Giacomo Carissimi – Jepthe

- Antonio Vivaldi – Gloria

- Giovanni Battista Pergolesi – Stabat Mater

- JS Bach – Mass in B minor

- Joseph Haydn – The Creation

- Igor Stravinsky – Symphony of Psalms

- Benjamin Britten – War Requiem

- Krzysztof Penderecki – St. Luke Passion

- Gyorgy Ligeti – Requiem

- Luciano Berio – Sinfonia

- Karlheinz Stockhausen – Stimmung

- Steve Reich – The Desert Music

- Iannis Xenakis – Nekuia

- Arvo Part – Passio