Blood Wedding

Young Vic, 11th October 2019

I got a bit nervous going into this. For those who don’t know, South African director Yael Farber has a certain style, an aesthetic, and approach to interpretation of classic plays, which isn’t too everyone’s taste. For me it works. Mies Julie, Knives in Hens, Les Blancs, even the much derided Salome at the NT, all drew me in. Very satisfying. We have her take on Hamlet also at the Young Vic to look forward to next year and newbie, the Boulevard Theatre, has lined her up to direct her compatriot, Athol Fugard’s, Hello and Goodbye.

For Blood Wedding though I had roped in the SO, a more forbidding critic, who is not, as most chums rightly are, as tolerant as the Tourist of, shall we say directorial longueurs. And this was near 2 hours straight through. On the benches of the Young Vic main space. And with her back playing up.

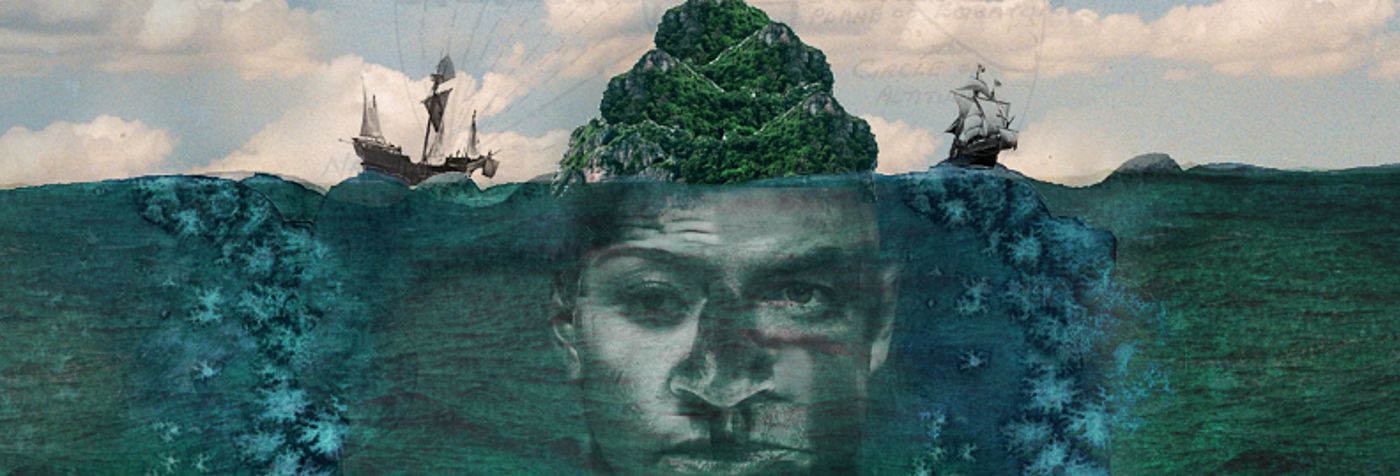

As it turned out I had nothing to fear. Lorca’s play, (his day job was poet after all), has a mythic and elegiac quality perfectly suited to Ms Farber’s ethereal approach, though this tale of forbidden love and revenge is not without drama and lends itself to a clear feminist interpretation. All this and more was on show at the Young Vic. A barely there, in the round, set design from Susan Hilferty, with occasional visual declamation via doors on one side, some artful cascades and a rope and harness which permitted muscular bad boy Leonardo (Gavin Drea) and absconding (nameless) Bride (Aoife Duffin) the striking means to pretend gallop. The intervention of the symbolic Moon (Thalissa Teixera), who can now add superb flamenco singing to her acting flair, and woodcutters (Roger Jean Nsengiyumva and Faaiz Mbelizi) made perfect, just about, sense. The bold lighting of Natasha Chivers, the score of Isobel Waller-Bridge, the spectral hum of Emma Laxton’s sound design, the balletic movement of Imogen Knight, witness the closing fight (overseen by Kate Waters) and subsequent requiem.

Most of all though Marina Carr’s beautiful translation. By shifting the setting of Lorca’s revenge tragedy to rural Ireland, though never quite leaving 1930’s Andalusia behind, Ms Faber allowed Ms Carr the opportunity to conjure an English language translation which was sympathetic to the poetry, metaphor and idiom of the Spanish original. A colonised Irish interior, suppressed by Church and State, bears obvious similarities to the paralysed, benighted Spain that Lorca delineated, critiqued and celebrated in his rural trilogy (Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba as well as BW). The hybrid setting also allowed the natural casting of the magnificent Olwen Fouere as the grizzled, austere Mother and the equally magnificent Brid Brennan as the Weaver. If I tell you that Annie Firbank as the Housekeeper and Steffan Rhodri as the outraged Father also graced the stage, along with relative newcomers Scarlett Brookes, (watch her closely in future) as Leonardo’s spurned wife and David Walmsley as the equally wronged Groom, then you can see that this was a grade A cast top to toe.

Lorca’s story is straightforward. Mother reminds son (the Groom) that his Dad and Bro were killed by the men of the Felix family next door. A dispute over land. Leonardo Felix and the Bride are still in love. Mrs Leonardo knows. The Mother finds out as well but decides to visit the Bride and her Dad. The wedding goes ahead by Leonardo turns up and steals the Bride. Outrage. Vengeance. Fight. Deaths. Sacrifice. It is very heady stuff but its chimerical qualities mean it is a long way from melodrama or even Greek tragedy. Closer to fable.

Anyway Yael Farber and Marina Carr have done a little nip and tuck with the plot but all the primitive elements are still there. That this is a traditional, brutally patriarchal society is never in doubt, as much but what the older women say, as the men, and yet there is still a sense of agency in the striking performances of Aoife Duffin and Scarlett Brooks. There is intentional comedy in the vernacular passages and there is no unintentional comedy in the brutal and fantastical scenes, (though once or twice it skirts close near the end – it is the women who mop up the blood). The cumulative effect is undeniably powerful even when the pace edges towards the, shall we say, Largo. In fact there is something of the minor key symphonic in Yael Farber’s reading.

I am not sure I would recommend this to fans of the Lion King or indeed anyway unfamiliar with this deliberately stylised auteur approach to theatre. On reflection I shouldn’t really have worried about the SO’s reaction. She reads books. Proper books. Lots of them. We are drowning in theme. Imagination, to augment the visual abstraction, is therefore no limitation for her.