Describe The Night

Hampstead Theatre, 23rd May 2018

In our country the lie has become not just a moral category but a pillar of the State. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

Describe the Night hasn’t gone down too well with the London critics. The SO and I think they might have missed a trick. It is ambitious, ranging across several periods of Soviet and post Soviet Russian history, with a fairly cavalier approach to naturalism, and mixes fact and fiction, real and imagined events. Its workshop-py creative methodology shows through, but it was for us highly effective and enlightening. We’ve seen a fair few other plays that have fallen far shorter, despite their more limited intent. So hats off to Rajiv Joseph the writer for giving this a go. I see he won an OBIE, off Broadway award, for best new play with this. That’s probably a bit generous, (or New York is lamentably short of new work which I refuse to believe), but it’s proof that this isn’t the disappointment some have claimed it to be.

Polly Sullivan’s design sees a cliff wall of grey metal filing cabinets punctuated with a raised corridor and spiral staircase down to a dark open space with a couple of spindly birches. This, with some nifty work from Johanna Town’s lighting and Richard Hammarton’s sound, serves as backdrop for an underground KGB/NKVD filing room, an interrogation room, a minicab office, a plush Moscow apartment, a sparsely furnished flat and a forest exterior. The action kicks off in Poland in 1920 during the Russo-Polish war, (a conflict itself near forgotten), where we meet Isaac Emmauilovich Babel played by Ben Caplin and Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov played by David Birrell. Both actors are superb by the way.

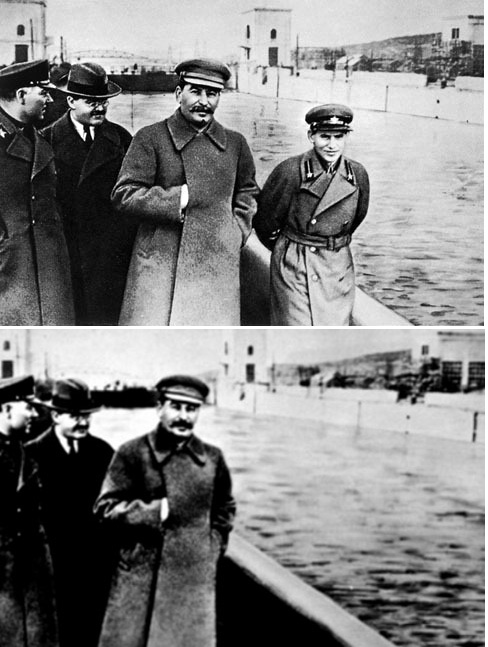

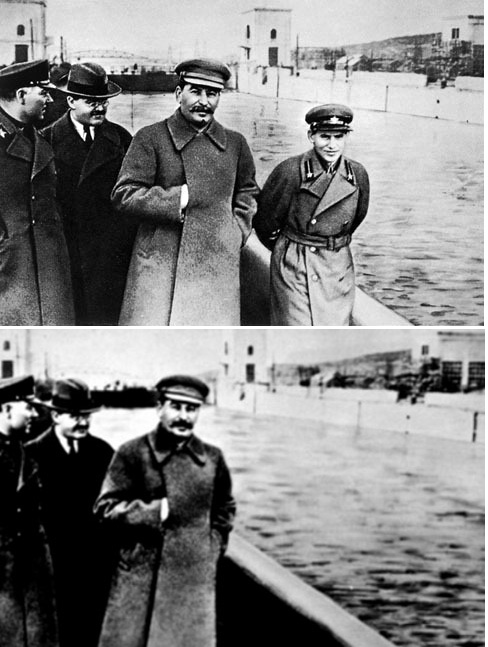

Now Babel was a writer whose stories about his childhood and this war were initially feted by the Soviet authorities but who was eventually arrested, his work confiscated, and he was executed in 1940. Yezhov was a small man, a party functionary, who drank to excess, but rose to become a favourite of Stalin and head of the NKVD through the Great Purge. Eventually though he fell foul of Stalin, his wife Yevgenia Solomonovna Feigenburg (Rebecca O’Mara) was arrested, and he too was executed in 1940, despite trying to save his skin by ratting on his friends including Babel. The photos above show how he was famously “non-person-ned” out of history.

The two meet in a forest near Smolensk as Babel is trying to “describe the night” around him. The literal Yezhov has very little of the poet about him, Babel relishes metaphor, and the two debate the nature of facts and truth. They strike up a firm, if unlikely, friendship. We move forward to 1930s Moscow where we see Babel, whose estranged wife is in Paris, begin his affair with Yevgenia, (which, in reality, had started earlier before she married Yezhov). In the next scene we have whizzed forward to 2010 and Smolensk, where the plane taking the Polish president, his wife and various political and military elite to the commemoration of the Katyn massacre of 1940, has just crashed. Journalist Mariya (Wendy Kweh) is looking to evade the police and enlists the help of Feliks (Joel MacCormack) to made good her escape so she can tell the story.

For those that don’t know the crash is still the subject of conspiracy theories, despite the Polish and Russian authorities concluding it was down to human error, and the Katyn massacre saw the murder of some 22000 Polish military and intelligentsia by the NKVD, although Soviet authorities only finally admitted this in 2010 having previously blamed the Nazis.

We also seen Wendy Kweh as cantankerous Mrs Petrovna and her “daughter” Urzula, played by newcomer Siena Kelly, living in Dresden in 1989. Urzula wants to escape to the West. They have come to the attention of Vova, extravagantly played by Steve John Shepherd, who you might know as one Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin. We see our putative Putin rewriting his own history in a confrontation with Yezkov, who has “lived on” to control the files of the NKVD/KGB. The real Putin’s early history is somewhat uncertain. Urzula may be the grand-daughter of the illegitimate child of Babel and Yevgenia, who ended up in an asylum thanks to Yezkov, unable to distinguish Babel’s stories from her own memory. Vova also interrogates, unpleasantly, Mariya, mirroring Yezkov’s interrogation of Babel.

And so the stories weave together and what is true and what is fiction becomes ever more uncertain. Babel’s diary, started in 1920, becomes the physical link between the “scenes”. Some have seen parallels in th eplay with other contemporary regimes alongside Russia where the truth is routinely manipulated. Rajiv Joseph is after all an American playwright. There is certainly much to ponder on from Mr Joseph’s particular narratives. and from his mix of fact and fiction, with even some magic realism thrown in, (never be tempted to drink leech soup). History has always been uncertain, from the moment it is “made”. Leaders and states have always sought to confound “truth”. limited only by their shame and intelligence, or lack thereof. The multiplicity of viewpoint that curses our contemporary digital world might seem like it has “never been as bad as this” but it has, as this century of Russian “history”, shows us. People lie. History is rewritten. Truth is fiction and fiction truth where only art might be trusted. The scale of Russia’s current strategy of disinformation may be exaggerated by technology but it certainly isn’t novel.

We thought that Rajiv Joseph’s text and Lisa Spirling’s (AD of Theatre 503) unhurried direction turned into an invigorating display of these “realities”. The cast all seem to have adopted a slightly forced quality in their delivery, which is though entirely consistent with the structure of the play and the world it inhabits. The “workshopped” construction, this version is different from its NYC cousin, does sometimes mean the pace eases ever so slightly, and the play is, perforce, disjointed, but the rewards more than justify this. (I am much happier saying this about Describe the Night than Maly Theatre’s Life and Fate, a similar dramatic exploration of Russian history). There is dark humour throughout. I can imagine a more fleet-footed production, (Stoppard and Kushner, also writers who relish the interplay of ideas and theatre, similarly need momentum), but the play is already asking a fair bit from its audience, (there is definitely a case for reading the excellent HT programme in advance), so a less stagey approach might risk confusion.

For the moment though this is well worth the effort. There are a few performances left at the HT but I have a feeling this will come back in some form or other and will be a “grower” whose reputation will grow with time. Not everything is what it initially seems maybe.

PS. The foyer of the HT contains some of the material from David King’s splendid collection of Soviet graphic art and photographs which formed the backbone of the recent excellent Tate Modern exhibition. There are a few links below to reviews of other cultural events that plough a similar furrow. Treat yourself.

Red Star Over Russia at Tate Modern review ****

Life and Fate at the Theatre Royal Haymarket review ***

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov at Tate Modern review ****

The War Has Not Yet Started at the Southwark Playhouse review ***

The Death of Stalin film review ****

Russian Art at the Royal Academy review ****