Academy of Ancient Music, Bojan Cicic (director and violin), Rachel Brown (flute and recorder), Rachel Beckett (recorder), Alistair Ross (harpsichord)

Bach and Telemann: Reversed Fortunes, Milton Court Concert Hall, 7th December 2017

I see I am now close to being a Academy of Ancient Music groupie. Not in a sinister way, that would be very strange. Just that I seem to pitch up to most of their London concerts. Unsurprising given their repertoire I suppose. And what a joy it always is to hear them play. This was no different. And I had a new chum in MSBD to join me.

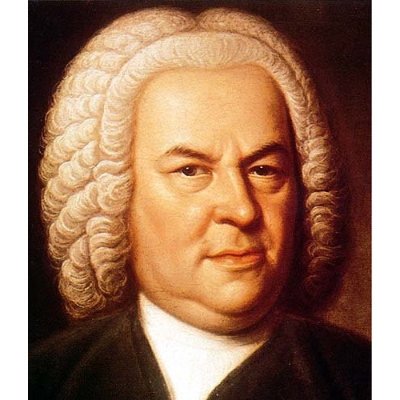

Now the theme here was to contrast the contrasting fortunes of a certain Johann Sebastian Bach and Georg Philipp Telemann. They were mates in the 1720s, 30s and 40s, with GPT becoming CPE Bach’s godfather, and both successively securing the reputation of the Collegium in Leipzig. Back in the day though Telemann (pictured above), with his suave, easy listening modelled on his French contemporaries, was by far the more popular composer, with JSB and his knotty, brainy counterpoint, and strong Lutheran faith, some way behind. As we all know JSB’s music languished for centuries, now some might say his is the daddy of all Western art music. Meanwhile whilst Telemann maintains a cherished place in the baroque world of the Baroque enthusiast, he is not much performed beyond this.

The influence of Vivaldi’s vast concerto output was much greater on JSB, and is clearly visible in the Brandenburg’s especially when played one to a part as here. In particular in the Fifth with its single tutti violin, though it is the solo harpsichord cadenza, the first ever of its type, that is the most memorable part of the concerto. Alistair Ross didn’t hold back once the harpsichord emerged from the string ritornello and his rubato was unleashed. A bit showier than Steven Devine in the last BC5 I heard in SJSS with the OAE. However, I think the Brandenburg 4 here with Rachel Brown and Rachel Beckett on the recorders was the highlight. Once the two Rachels got into the swing of it there was no stopping them, propped up by Bojan Cicic masterful violin playing, and by the end those recorders produced as sweet a sound as you could imagine (not always the case for the period recorder).

Having said that I think the most satisfying piece of the evening was the Telemann Concerto for flute and recorder. He wasn’t the only one to pair the “old” and the “new” wind instruments, Quantz was on to this, but he clearly mastered it. Written in 1712, the Concerto has some very attractive galant homophonic playing from the two instruments looking forward to the Classical. Elsewhere the soloists chase the lines from one to the other against very attractive dances, including nods to the eastern European folk tunes that he studied. The French influence on GPT is more apparent in the Overture suite, (he wrote over two hundred of these), with its simple dance rhythms and story based on Don Quixote. There is plenty of easy on the ear comic effect, (listen out for donkeys), and lots of colour. It is all so pleasant (though if I was critical maybe a tad too pleasant).

So another fine concert from the AAM who really seemed to be enjoying themselves. As I think did MSBD. In fact I know he did as he said so. I shall miss the AAM Messiah in the Barbican Hall and their intriguing Haydn and Dussek programme in April, but will be back here for the 15th February Pergolesi, Corelli and Handel gig, and for the 31st May concert in the Hall with Nicola Benedetti. Unmissable I reckon.