Richard III

Headlong, Alexandra Park Theatre, 17th March 2019

Right. Let’s get the gripe out of the way. Maybe in the smaller venues where this production will tour it might creep up to a 4* but Alexandra Park Theatre, whilst an undeniably superb space after the refurbishment, is just a little too cavernous to accommodate the claustrophobic history/tragedy/comedy/thriller/psychodrama/vaudeville which is Dickie 3.

Chiara Stephenson’s Gothic, dark, old-school castle with a twist, namely the introduction of multiple full length, revolving mirrors, together with the lighting of Elliot Griggs, is a winner set-wise. But it utilises barely a third of the huge proscenium stage, and I would guess, since all is shielded in dark fabric, only a similar portion of the depth. To rectify this the actors, in addition to coming on and off through the glass revolves, enter from the auditorium to the side of the stage, and, for the London scene, pop up in the “slips” and bark back to the stage. It is the right look for John Haidar’s galvanic production and Tom Mothersdale scorpion delivery as Dickie but seems lost in all this volume. As do the lines. Not because of the delivery. In most cases this is sound as a pound but set against George Dennis’s throbbing, pounding, electronic sound the intensity is diluted, and occasionally, for the aurally challenged such as the Tourist, lost completely.

Now this being a Headlong production, (albeit in conjunction with Ally Pally, the Bristol Old Vic, Royal and Derngate and Oxford Playhouse, all of which it will travel to, as well as the Cambridge Arts Theatre and Home Manchester), there is still much to admire. With the Mother Courage, This House, Labour of Love, People, Places and Things, Junkyard, The Absence of War, American Psycho, 1984, Chimerica, The Effect, Medea and Enron, Headlong has been responsible for some of the best theatre the Tourist has seen in recent years. He even liked Common, John Haidar’s last outing, putting him in a minority of one. He would therefore never miss anything the company produces. All My Sons at the Old Vic and Hedda Tesman at Chichester already signed up with willing guests.

John Haidar has opted to sneak in a bit of Henry VI to provide context, (complete with first taste of murder before that “winter” even starts), juggles the standard text and cuts out superfluous characters, though doubling is kept to a minimum, and generally encourages a lively approach to the verse, (though nowhere near the gallop of Joe Hill-Gibbons’s Richard II at the Almeida recently) . This means each half barely ticks over into the hour. The focus then, as it should be, is on Tom Mothersdale’s Richard, and the “family” saga, if you will, a family from which Richard is permanently excluded, rather than the politics. Tom Kanji’s Clarence doesn’t take up too much time, the other assassinations are similarly rapidly dispatched, Stefan Adegbola’s smug Buckingham and Heledd Gywnn’s Hastings, (as arresting a presence as she was in the Tobacco Factory’s Henry V), take precedence in the jostling for power, and the scenes with the three women, Dickie’s, to say the least, disappointed, Mum, the Duchess of York (Eileen Nicholas), Edward IV’s Scottish widow Elizabeth (Derbhle Crotty) and sacrificial lamb Anne (Leila Mimmack), are given plenty of air time.

With Heledd Gwynn doubling up as Ratcliffe, Tom Kanji as Catesby and Leila Mimmack as Norfolk, the production achieves an admirable gender balance and also tips Richard’s murderous ascendancy into a joint enterprise, at least until he shafts his mates. The main cast is completed with John Sackville’s ghostly Henry VI, Michael Matus as Edward IV and then Stanley and Caleb Roberts as Richmond (and utility messenger). The stage then is literally set, what with the opening soliloquy and those mirrors, for Dickie to slay his way to the ghostly visitations. Each murder is marked by a red flash and a loud buzz just to make sure we get it.

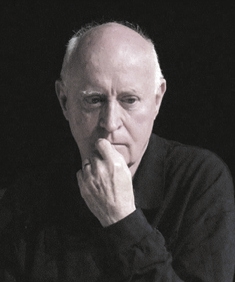

Now the Tourist has seen young Mothersdale up close in the slightly disappointing Dealing with Clair at the OT recently, in the magnificent John by Annie Baker, as well as roles in Cleansed at the NT and Oil at the Almeida. He’s got it, no doubt. As he shows here. And, as he capers around the stage, in dark Burgundy suit and leather caliper, long-limbed, lank-locked, threatening, cajoling, pleading, squirming at Mummy’s rejection, he is certainly the “bottled spider” of Will’s description. But I am not sure he finds an angle. There is the caricature Richard of Thomas More Tudor myth, as Reformation Elizabethan England found its way in the world ordained by God. There is Richard as psycho executing to a plan, villainy as predestination. There is nudge, nudge, wink, wink comedy Richard who recruits us into the fun. Or there is poor, diddums, “nobody loves me so I’m going to show you” Richard who can’t stop once he gets started. And more. With multiple permutations.

Here we seem to get a bit of everything in this swift, safe production. Not the monomaniac man-child, (any resemblance to a current world leader is surely entirely deliberate), of the brilliant Hans Kesting in Kings of War, not the compulsive egotist of Lars Eidinger in the Schaubuhne production at the Barbican, not the amoral sociopath of Ralph Fiennes at the Almeida with that infamous rape scene, not the trad manipulator of Mark Rylance at the Globe. Of the other recent Dickie’s that the Tourist has enjoyed Tom Mothersdale comes closest to Greg Hicks’ take in the pint-sized, though still extremely effective production, under Mehmet Ergen at the Arcola in 2017. Except that Greg Hicks made every single word count and plumbed some very ugly depths in Richard’s misogynism and unquenchable grievance. And with chain permanently attaching arm to leg he offered a stark visual reminder of his “deformation”.

There are some fine moments, the “seductions”, the ghosts behind the mirrors, TM cringing at Mother’s curses and her recoiling from his touch, some meaningful gobbing, the writhing in the Bosworth mud at the end, and, like I say, this will probably work better at, say, Bristol or Oxford, but I would have preferred a more thoughtful, and yes, longer, interpretation. Still the one thing you know about Richard III’s, like Macbeth’s, Lear’s and Number 38’s, there will be another one along shortly.