London Philharmonic Orchestra, Thomas Adès (conductor), Kirill Gerstein (piano), Ladies of the London Philharmonic Choir

Royal Festival Hall, 23rd October 2019

- Sibelius – Nightride and Sunrise, Op 55

- Thomas Adès – Concerto for piano & orchestra

- Holst – The Planets, Op 32

An opportunity to break MS into the world of modern/contemporary classical music in the admittedly unthreatening person of the mighty Thomas Ades, here both composer and conductor. Mr Ades is quite possibly my favourite living composer and his take on Beethoven with the Britten Sinfonia provided some of my favourite performances in the last few years. I am pleased to say that my favourite son, whose intellectual curiosity fortunately knows no boundaries. is now a convert. Indeed we both regarded this UK premiere of TA’s 2018 piano concerto, his second after In Seven Days from 2008, as the highlight of the evening, surpassing his predictably astute reading of The Planets.

First up though Sibelius’s sleigh ride inspired tone poem. Now there must have been a time when I thought I liked Sibelius. I have a symphony cycle recording from Simon Rattle and the CBSO and the violin concerto, and I seem to remember both were purchased on the back of live renditions. But now I find him pretty much unlistenable. Big slabs of music where not much happens. Organic yes, nature in all its glory as here, yes, clear themes gently mutated. Night Right and Sunrise is a game of two halves. The chugging sleigh ride rhythms giving way to a restorative chorale. Audience and orchestra deep in concentration, the string players especially in that dotted quaver/semi-quaver repeat, but even TA was unable to help me get it.

Kirill Gerstein, with TA conducting, first performed the piano concerto with the commissioning Boston Symphony Orchestra in March, with performances following in New York, Leipzig, Copenhagen and Cleveland, with Helsinki, Munich, Amsterdam and LA to come. So you can see that this is a “big thing” music wise and will have given TA and KG the opportunity to play with some of the top rank orchestras worldwide. I would be very surprised if this isn’t seen as an instant classic with KG, who plainly loves it, (already performing from memory), being compelled to yield his first mover advantage in the very near future. Hopefully he will get his recording in first as this definitely deserves it.

The first movement, marked Allegramente, jolly, opens with drum rolls and is in sonata form with a march tune between the two themes and an extended cadenza at the end. The second slow movement, Andante gravemente, starts with a melody and countermelody after a chordal intro, and follows this with a lovely second melody idea set against a rising harmony. The final Allegro giojoso restores the merry mood, with a jaunty canon following an opening tumbling theme before a brass clarion heralds a new bouncy boogie with a choral climax. These themes and the call to arms that punctuate them are reworked in many ways but always with soloist, orchestra and conductor flaunting their Gershwinian jazz trousers. Like so much of TA’s music it probably couldn’t exist without Stravinsky, Ravel and Britten, but there is also, more surprisingly as sense of Bartok in the slow movement and Rachmaninov in the finale. But it is Prokofiev that keeps coming to mind especially in the improvisatory piano line with shifting tonality, syncopation, counterpoint, imitation, repetition and light-hearted dissonance all contributing to the buoyant mood. Like a contemporary artist who believes in the enduring value of paint and colour, TA takes inspiration from the best that his forebears have come up with in the last 150 years for this combination and defiantly reworks it. We weren’t the only happy punters.

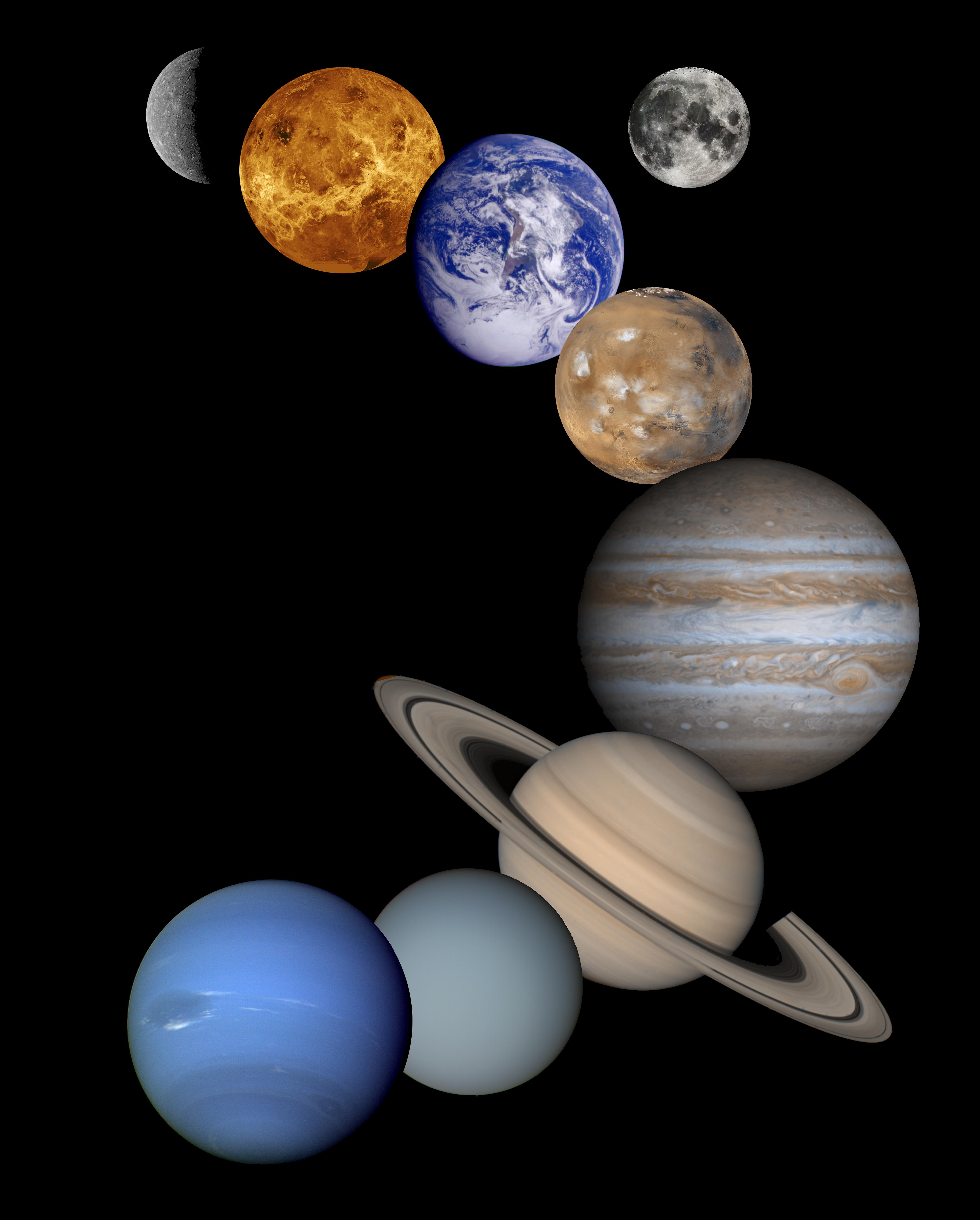

I love The Planets but recognise that, outside of the big thrills, over familiarity can sometimes dampen the wow factor. Not here though. As with his fresh take on Beethoven, TA, isn’t all driven tempi and flash harry. There are passages of surprisingly muted, dare I say traditional, interpretation, in Mars, in Jupiter, in Uranus. Mind you that’s not to say the LPO, all 109 of them just about crammed on to the RFH stage, didn’t make a heck of a racket in said Mars and Jupiter. Mercury and Uranus showed up TA’s ear for detail amidst the perky Disney bops. However it was in the pulse-y interplay between harp and flute and the strings in Saturn and Neptune that impressed me most.

Top class. MS has asked for another. I will need to tread carefully after this.