Divine Geometry: London Symphony Orchestra, Kristjan Jarvi, Simone Dinnerstein (piano)

Barbican Hall, 29th November 2018

- Charles Coleman – Drenched

- Charles Coleman – Bach Inspired

- Philip Glass – Piano Concerto No 3

- Kristjan Jarvi – Too Hot to Handel

- Steve Reich – Music for Ensemble and Orchestra

Funny one this. As part of our project to embrace the classics of minimalism the Tourist, MSBD and MSBDB schlepped off to the Barbican. Primarily to hear the new(wish) Reich piece in its UK premiere, and to catch up with the Glass, similarly making its UK debut. Didn’t really have a Scooby about the other pieces I am afraid.

Now somewhere in Estonia, (actually it relocated to the US) there is a factory which produces conductors. It is family owned and goes by the name of Jarvi and Sons, (in Estonian obvs). For Kristjan, along with older brother Paavo, is son to the veteran, and oft recorded, conductor Neeme. Sister Maarika plays the flute though I have no doubt she too is a dab hand with a baton.

Anyway young Kristjan, who has the gig as the AD of the Baltic Sea Philharmonic which he founded, sees himself as a bit of a musical chameleon and genre-buster. Having got his hands on the LSO again he wasn’t about to waste the opportunity to showcase one of his own works, Too Hot To Handel, nor a couple from his mate Charles Coleman. Drenched takes Handel’s Water Music as its starting point, and Bach Inspired, er, a string-only snatch from the Mighty One’s Well-Tempered Clavier and his “Nun common Der Heiden Helland” chorale, plus a couple of his own movements. Too Hot …. you can work out for yourself. Suffice to say it has pretty much undigested chunks of GF’s Concerto grossi mashed up with KJ’s own Stravinskian, post-minimalism, as well as a lot of running around for the LSO’s three percussionists, Neil Percy, Sam Walton and Jake Brown, and a starring role for Chris Hill on bass guitar (I kid you not).

Worshipping at the altar of the Baroque Gods and drawing the parallels with the Minimalists is self evidently “a good idea” but always better done with the C17 and C18 originals. These pastiches, whilst certainly not dull, and played with gusto by the LSO, ended up as classic classical “classic rock” if you get my drift. Not quite Smashie and Nicey, but skirting awfully close. The Coleman pieces, especially Bach Inspired had a bit more heterogenous invention, and wit, about them but even so it was all a bit weird to be honest. At near 40 minutes and over 13 movements, Jarvi’s own work I am afraid outstayed its welcome, was shown the door but still came back again.

As for the main events, well the Piano Concerto No 3 was a little too close to the pleasant warm waves of swirling arpeggios that Philip Glass can presumably churn out in his sleep and the Steve Reich piece was, guess what, just amazing.

The Concerto was written for this evening’s soloist Simone Dinnerstein and premiered in Boston in 2017. Glass, now 81, has moved a long way from the “hard-core” rhythmic minimalism (“repetitive processes” in his argot) of the 1960s and 1970s. His music now is much more melodic, chromatic, even romantic. When he composes for piano, as with the three concertos, the lovely Etudes and Metamorphosis and the film music transcriptions, he is a right old softie and gets all emotional. It can be moving and occasionally stirring stuff but it is mostly like being immersed in a nice warm metaphorical bath with Brahms and Rachmaninov.

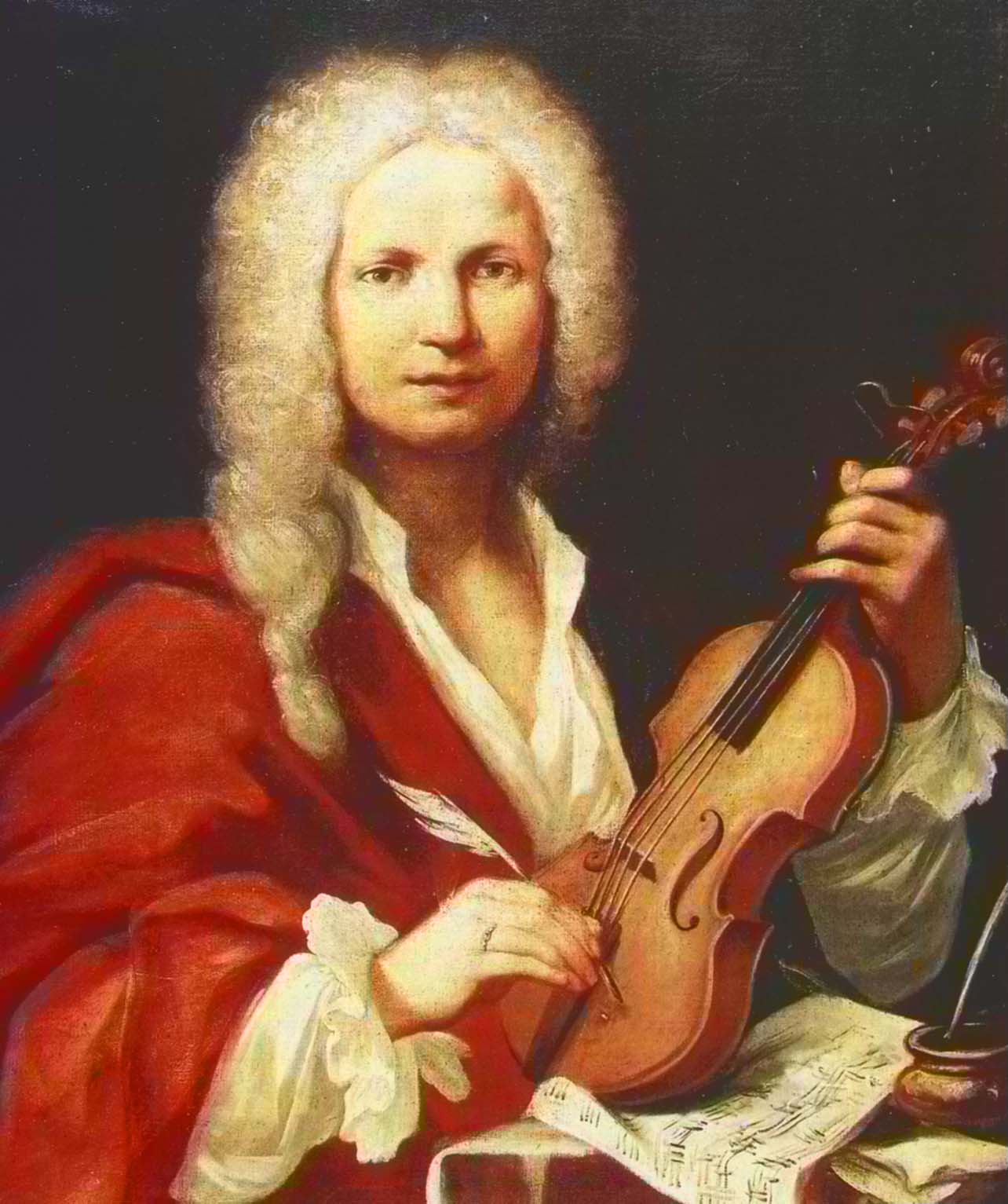

You could be forgiven for thinking popular art-house film soundtracks, which have been, after all, a fair contributor to the old boy’s estate in the last few decades. And one of the reasons, perhaps along with his generosity in collaboration, why his music has been so influential. In fact it is pretty difficult to think of another composer of music in the second half of the C20, and into this millennium, his musical ideas have been quite so pervasive. It will be interesting to see whether Glass’s legacy, like much of post-modernist culture, survives. Whilst love for Schubert, another compositional production line, who I suspect Glass would most liked to be identified with, has pretty much continued to increase year in, year out since his early death, other comparable piece-work composers from the Baroque itself, Bach say, or Vivaldi, spent hundreds of years being ignored. Mind you in the age of digital junk it will be hard to forgot anything ever.

Yet amidst all the familiarity Glass is still capable of surprises and here it comes in the final movement, which is simplicity itself, being a homage of sorts to Arvo Part, he of the “holy minimalism”, with a simple, chiming melody over a bass drone. The introspective concerto, which is essentially three slow to medium paced movements, begins with soft oscillating chords against a processional base-line, which drifts in and out of the similarly paced orchestra. Crotchets become quavers then triplets, rising to a swell and then subsiding. The second chaconne-ish movement is all repeated arpeggios which ends with the unflashiest of cadenzas.

As its dedicatee, and given she is an acknowledged interpreter of Glass’s music, Ms Dinnerstein, who is what you might call a “self-made” performer, more in line with the You Tube pop generation, was unsurprisingly accomplished in her playing, technique, emotion and understanding all present and correct, and if it didn’t wow then that is more the fault of the music than her or the LSO strings. She encored with a Glass Etude. I would have liked more of those.

In less than a month’s time Philip Glass’s 12th Symphony will be premiered in LA under the baton of fellow “minimalist” grandee John Adams. You can’t fault his work ethic.

Music for Ensemble and Orchestra, premiered earlier this year in NYC, is Steve Reich’s first large scale orchestral work for 30 years, following The Four Sections in 1987. Reich is of course as much performer as composer and his ostensible reason for avoiding the orchestra genre was that performers were not really up to the task. Fair enough, but, as he admits, that is no longer true as there are now orchestral players, notably percussionists, but also specialists in the other sections, as well as the latest generation of conductors, who are more than up to the task, and who love and relish the challenge of creating his stunning sound-world. Mr Reich is a year older than his peer Mr Glass but they are chalk and cheese when it comes to productivity, as well as, despite the “minimalist” label, musical style.

SR can go a couple of years without a new piece. This is is no way a criticism for when they do arrive his compositions continue to be works of staggering genius. This, of course, assumes you are predisposed to his marrying of pulse, rhythm and process. Here he has contrasted an “ensemble”, lead strings, principal woodwinds, tuned pianos, vibraphones and keyboards, with an “orchestra” which adds a full string section and brass, in the form of four trumpets, to that ensemble.

The work is made up of five sections/movements, in typical Reich style simply numbered 1 to 5, which together form a Bartokian arch. the tempo is fixed across the sections but the speed varies according to note value: 16ths, 8ths, quarters, then 8ths and 16ths again. The key similarly changes across the movements, a minor third each time, from A to C to E flat to F sharp and back to A. All this remains moreorless gobbledygook to the Tourist but I reckon, as and when a recording appears, the structure that can be felt on first listening, will be understood by this musical dummy after repeated exposure. That is the big picture: second by second though it is the magical intricacy of melodic fragments repeated, echoed, chased and overlapped by different paired members of the ensemble with the rhythmic backbone provided by the rest of the orchestra. A Concerto grossi to match Handel though maybe not quite the Daddy of the form, Corelli.

Mr Jarvi, who likes a lively workout on the rostrum, seemed to have the measure of the piece, though I wouldn’t mind hearing the LSO take it on again under, say, their Conductor the Laureate Michael Tilson Thomas. He is, after all, the expert on great American music of the C20 and there was, I’ll warrant, a Coplandian/Ivesian twinkle in some of Reich’s invention. I see he will be premiering it in San Francisco next year as it revolves around the remaining or the six orchestras that co-commissioned it.