Leopoldstadt

Wyndham’s Theatre, 29th January 2020

A new play from the venerable 82 year old Sir Tom Stoppard. Not our greatest living playwright. That is Caryl Churchill, but he does know his way around a text. So booked early, for early in the run and before knowing too much about it.

You will likely know by now that Sir Tom has chosen to delve into his family’s own history and his Jewish heritage for this play, which I can see would be a fitting swansong, if swansong it is. He was born in Czechoslovakia, but escaped to Britain with his family ahead of the Nazi occupation, and was educated in India and then Yorkshire. Whilst he had become aware in the 1990s of the full extent of his roots, (which his mother had chosen to shield him from), as well as the fact that many of his relatives had died in Nazi concentration camps, and he had indicated that he would likely write a play based on this history, he had been ambivalent about making it too personal.

I don’t know how much of the plot, and specifically the key events which punctuate it, are drawn from TS’s own family history, nor indeed how closely the characters resemble his own forebears, (though the character of Leo is surely autobiographical), but there is no doubting his emotional investment in this grand saga. Particularly at the end, in an epilogue which is as moving as anything you might ever see on stage.

We kick off in Vienna in 1899 at a gathering of the Merz and Jakobovicz families at Christmas (and later passover). Bullish businessman Hermann Merz (Adrian Scarborough, on his usual top form) is married to gentile Gretl (Faye Castelow), having, pragmatically, converted to her Catholicism. They have one son Jacob. Hermann’s sister Eva (Alexis Zegerman) is married to obsessive mathematician Ludwig Jakobovicz (Ed Stoppard, yes, he is) who has two sisters, Wilma (Clara Francis), married to Ernst (Aaron Neil), and Hanna (Dorothea Myer-Bennett, continuing the Tourist’s fortunate habit of seeing everything she does on stage), who is married to Kurt (Alexander Newland, who we meet later on). With their various kids, cook Poldi (Sadie Shimmin), parlour maid Hilde (Felicity Davidson), nursemaid Jana (Natalie Law) and all presided over by Grandma Emilia (Caroline Gruber). Thank goodness for the family tree in the programme which the Tourist furtively turned to early doors.

With this many characters, and to set the contextual and didactic balls rolling, and because this is what Sir Tom does best, there is a lot of serious chat going on, as we learn how these well-to-do, educated and largely assimilated Jewish families see themselves, their faith, culture and economy, at a time of great change in Europe’s still premier metropolis. And, inevitably in the first act, bucketloads of exposition. The Merz family doesn’t live in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt district but its status as the centre of Jewish life in the city looms large. The anti-semitism is subtle as well as overt, but its deep historical roots are unmistakeable. Hermann tries and fails to join the jockey club, Ludwig’s hopes of a professorship are far-fetched, and ugly truths are revealed, along with the superb Luke Thallon’s cruel Aryan officer, Fritz.

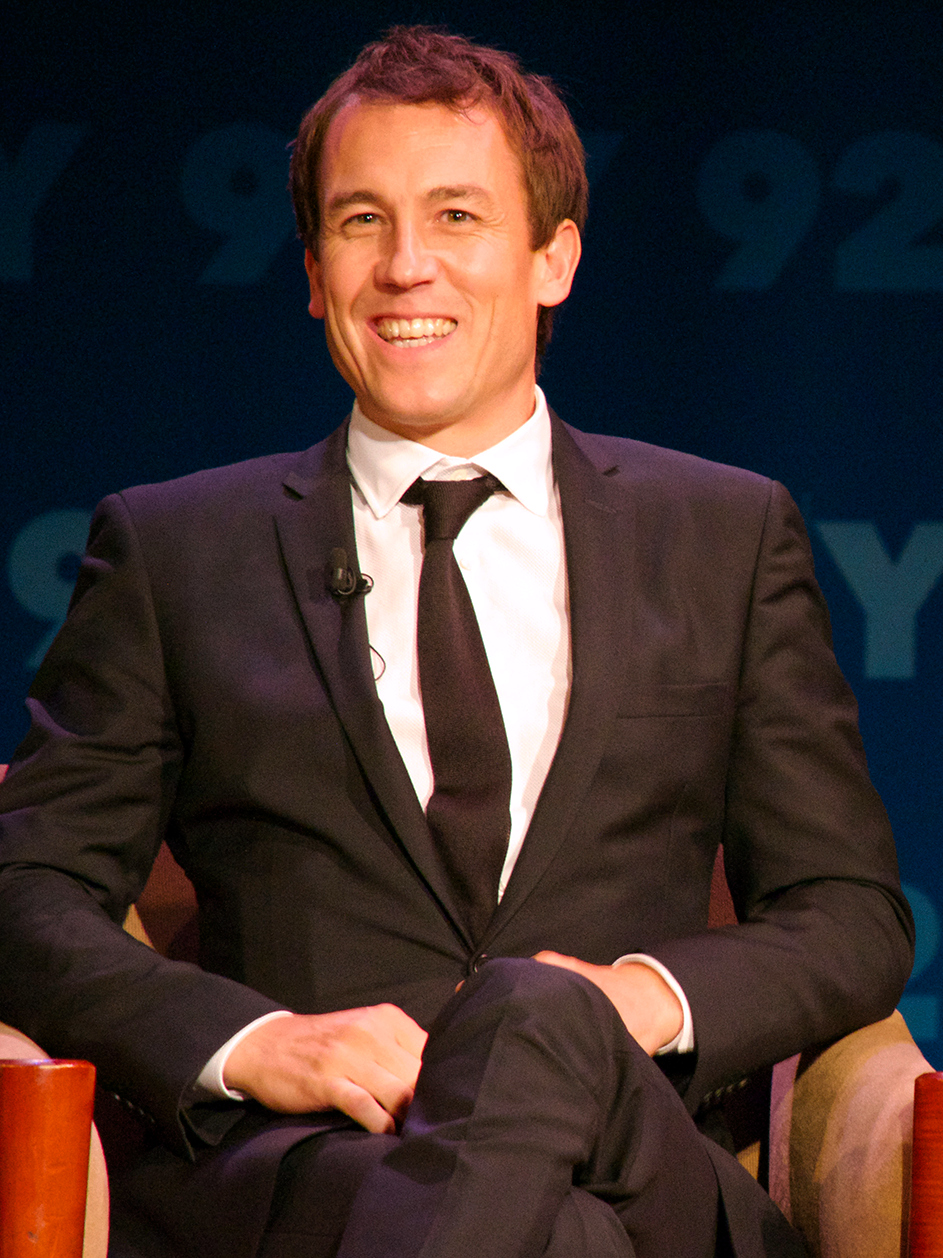

The play really gets going then after the interval, as we move first to 1924, another family gathering for a circumcision, meeting the cosmopolitan children of the four couples, and then, momentously 1938, and the grandchildren. This is the cue for high drama, for example, the forced repossession of the Merz family home, and eviction, Kristallnacht (vividly realised through Adam Cork’s brilliant sound design), the memory of Pauli (Ilan Galkoff) lost in the WWWi trenches. Then, finally to 1955, when Leo (Luke Thallon), the English emigre son of Nellie (Eleanor Wyld), daughter of Eva and Ludwig, and Nathan (Sebastian Armesto, also doubling), son of Sally (Ayve Leventis), daughter of Wilma and Ernst, are brought together by Nathan’s sister, Rosa (Jenna Augen). This, or something like it, is, I’d like to think, how Sir T first encountered his own history, and planted the seed for Leopoldstadt.

The dialogue is direct, even during the debates on, variously, identity, assimilation, prejudice, Zionism, the recurring history is familiar and there is none of the intellectual trickery that powers Sir T’s back catalogue though there is a bit of heavy lifting from a recurring cat’s cradle metaphor. The family’s beliefs in science, justice and rationality are crushed by the rise of Nazism, but it is the personal loss more than the collective that, eventually strikes home, with Hermann’s descent the most affecting. It is a slow burn mind you, and Patrick Marber’s direction is perhaps a little too respectful. Richard Hudson’s painterly design. together with Neil Austin’s lighting and Brigitte Riefenstuhl’s costumes ooze period detail, but further hinder any opportunity for many of the 26 strong cast (not including the kids) to make a distinct mark.

Still if this is to be Sir T’s last play then why shouldn’t he tell his story his way, given his immense contribution to British and World theatre across his career. At our early viewing (the SO was a more than willing accomplice) the audience was engrossed throughout, if nor utterly captivated, and I suspect many will have been grateful to have had their emotions, perhaps even more than their intellects, engaged. The story of this horror has been told in many ways before, and should continue to be told, but Sir T has found a way to tell it that, whilst not theatrically radical, is profoundly moving, as well as stuffed with learning.

I have no doubt it will be back when we reach the other side, and it is not hard to see it being repurposed for the small screen.