Titus Andronicus

Barbican Theatre, 13th December 2017

Titus Andronicus is a comedy right. Yet I see it is customarily bracketed with the other Shakespearean tragedies, and here forms part of the RSC’s latest take on the quartet of Roman tragedies, entitled, er, Rome.

Now I know this comedy/tragedy/history play division is confusing at the best of times, but here, trust me, it is piffle. Big Will packed sad bits and sundry trials for his heroes even in the lightest of his confections. And, even in the most miserable passages of the serious stuff there are plenty of gags, (though sometimes a bit obscure I admit). In this play though all I really see is one long, (it only just about stops short of one scene too many), parodic, black comedy. This kind of thing is ten a penny now, particularly in the world where art-house and horror cinema mix, but big Will was on to this over 400 years ago. Since there has never been anyway to match him, in English at least, in most other forms of dramatic expression, it should be no surprise that he could effortlessly turn his pen to a genre p*ss-take.

After all the revenge tragedy had been a sure-fire box office hit in the previous three decades before Titus Andronicus hit the South Bank in 1594. Jasper Heywood had translated Seneca’s tragedies, Troades, Hercules Furens and, most famously, Thyestes, in the 1560’s. Thyestes particularly spawned a whole host of imitations, not least of which Titus Andronicus itself which draws on elements of Seneca’s gore fest. (I see that the Arcola staged a version of Caryl Churchill’s version of Thyestes directed by Polly Findlay a few years ago. Wish I had seen that). Norton and Sackville’s Gorboduc came out in 1561. First early modern tragedy, first blank verse drama, a veiled commentary on contemporary politics. (Wish I had seen that too. Especially with Lizzie I in the room). And, most successfully, Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy had wowed audiences in the 1580s already.

So Will S and chums were keen to meet the public demand for extreme violence on stage. And a few plot holes, (Will was never one to worry overmuch about these), wasn’t going to stand in their way. Lest we forget though young Will wasn’t yet the dominant force he would become in English drama. One farce, The Comedy of Errors, one decidedly dodgy comedy, The Taming of the Shrew, and a few, albeit brilliant, propaganda plays, Henry VI (1,2,3) and Richard III, might not have been enough to guarantee a hit. So Will collaborated with one George Peele, who apparently contributed the busy first Act, (where Titus A, bloody livid after losing most of his sons in the war with the Goths, sets up the cycle of revenge), the scene at the beginning of Act II when the dastardly Aaron goads the Goth brothers, Chiron and Demetrius, into planning their heinous crime, and the beginning of Act IV, the reveal with its classical allusions, specifically Ovid and the rape and revenge of Philomela. Remember dear readers the several hundred year veneration of Classical Antiquity ushered in the patriarchy’s very unhealthy obsession with sexual violence as well as nice pictures of urns.

Anyway it seems to me that Peele’s contributions provide the stout backbone of the classically driven tragedy plot which then leaves Will to engage in the genre twisting anddark humour. Now I admit that a lot of what I thought was funny in the play was not always shared by the entire audience. There were a few other titterers at some of the smutty innuendo and the ludicrous ,cartoonish violence. There may even have been others wryly smiling at Marcus Andronicus’s flowery blank verse when he stumbles across the mutilated Lavinia. For this is the only way I can fathom this bizarre incongruity. He should be hollering for the Roman equivalent of an ambulance not waxing lyrical about her fragrancy and showing off his classical education.

What else? Saturninus suddenly getting the hots for Tamora. The Roman brothers “accidentally” falling into the pit containing Bassanius’s murdered corpse. Titus A thinking it is a good idea to chop his hand off. His chat with that poor fly. Lavinia spelling out the names of the Dumb and Dumber bad boys in the sand. Little Lucius’s knowing asides to us followed by a gag about Horace’s poetry. Aaron taunting us with his “will he, won’t he” dangling of his new baby and then the unsuspecting Nurse talking herself into an early grave. The gruesome pie, of course, and finally the three blink-and-you-miss-them concluding deaths in as many seconds

Others may want to take this all at depressing face value. I can’t. The only way to accommodate the abrupt shifts in tone, I reckon, is to assume that Will was trying to subvert the very thing he had created. I think director Blanche McIntyre is happy to go with the blackly comic flow without over-egging it. Well maybe the messenger on a bike was a bit over the top. Though it got the biggest laugh of the night, proving that nothing works better than a blatant sight gag in Shakespeare.

Make no mistake TA was a huge hit in its first few years but thereafter was confined to the scrapheap by most every commentator until, surprise, surprise, Messrs Brooke and Olivier, worked their magic in 1955. Trying to take this too seriously just want wash in my book. It isn’t a sick pantomime for sure, there is too much stunning rhetoric to allow that to happen, but neither is this a proto-Lear. I don’t see any point in trying to fight against the dramatic conventions which shaped its construction, or in trying to pretend there is some great insight into the human or political condition here. The creative team seem to be suggesting this could be a metaphor for our uncertain political age. Nonsense. Things might look a bit sh*tty out there, and civic discourse is coarsening, (in part because every Tom, Dick and Harry think they can have a view – ah the irony), but government in Western democracies isn’t yet based on vendetta and cannibalism.

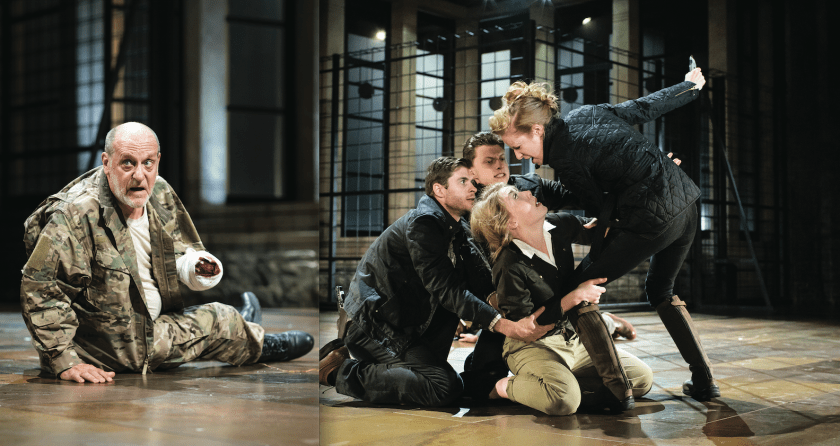

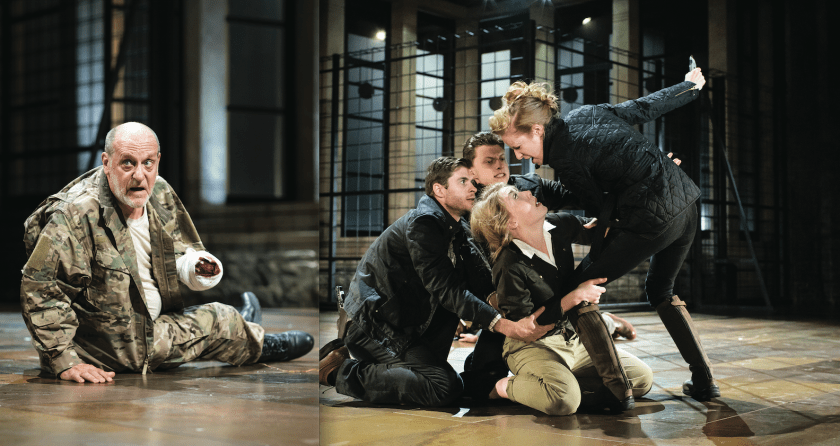

David Troughton as Titus A kicks off his performance as stiff, martial hero, a wizened Coriolanus, wedded to the justice of the battlefield and certain in his pronouncements. A brass band follows him around – a smart touch. Limbs and mind unknot as events unfold so that, by the end, he is as batsh*t crazy as you like in chef’s whites and a nice line in one-armed knife work. Martin Hutson’s toddlerish, paranoiac Saturninus is very amusing, and the similarity with a certain contemporary leader well observed. Attempts to shoehorn in other echoes of a chaotic White House administration, and some street riots signposted “austerity”, are less effective however. Hannah Morrish didn’t get much of a look in as Virgilia in the RSC Coriolanus but here, as a noble Lavinia even when mute, she was excellent. Nia Gwynne’s Tamora was a little underpowered. In contrast Stefan Adegbola as Aaron, once he get to open his mouth after prowling around in Act I, didn’t hold back. Let me say it. Aaron is an ugly, racist caricature which pandered to Will S’s contemporary audience. No Othellian complexity here.

Having guffed on above about embracing the funny side of TA I must say that, when the mutilation comes on stage, this production doesn’t hold back on visceral impact. A couple of nurses, a surgery trolley, a saw and some top-drawer illusion courtesy of Chris Fischer mean TA’s hand-job, (as it were), is the best of the gruesome bunch with the stylised throat-slitting of the two bad boys, suspended upside down, coming a close second. Lavinia’s rape and mutilation was genuinely shocking.

So a production that, with a few maybe superfluous details, looks (and sounds) the part and delivers unflinching horror realism. A memorable central performance, with some excellent support in large part. A director who is not afraid to go where the words and plot take her, even if this points up the anachronistic structure of the play. Ms McIntyre is also very alert to the nature of our “enjoyment” of the play. Is it a bit sick to laugh at some of this? And if you are horrified then why did you turn up in the first place? Just how far can we go in pretending that Shakespeare is always “for all ages” or should we recognise that, early on at least, he was bound to his own time?

Of course it could just be that the diet of Tarantino and Korean revenge films which brings BD and I together has left me inured to this kind of thing. Anyway go see for yourself. There are a few tickets left for the remaining performances. And don’t forget to insert your tongue firmly into your cheek as you walk in.