Copenhagen

Minerva Theatre Chichester, 6th September 2018

Michael Frayn wrote the funniest stage comedy of all time. Noises Off. OK well maybe it is only is the funniest of those comedies that I have seen. And maybe the two productions that I have seen, the NT one from 2000/2001 directed by Jeremy Sams, and the 2011/2012 Old Vic revival directed by Lindsay Posner, show it off to best effect. And the fact that Mr Frayn has sharpened it up with re-writes since it first appeared in 1982 helps. It is a farce about a farce about a farce and is brilliantly constructed. For sure the belly aches come from the visual humour and slapstick but real comedy also emerges from the characters “on” snd “off” stage personas and their relationships. Everyone should see this once in their life, (but not the film version – the whole point of this is that it is a theatrical experience and the film is rubbish). LD remembers it as the funniest thing she has seen on stage and she was only 10 at the time.

We also have to thank Mr Frayn for his pitch perfect English adaptations of Chekhov. The magic of Chekhov can prove elusive but a text from MF gives a good chance for a production of walking the tightrope between pathos and comedy. There are his novels as well. I have though, until now, never seen either of his more recent dramatic triumphs, Democracy or Copenhagen.

So thanks to Chichester Festival Theatre for putting on this revival. And to recruiting a cast of the calibre of Charles Edwards, Patricia Hodge and Paul Jesson. And to persuading, if he needed persuading, Michael Blakemore, who directed the NT premiere in 1998 to wave his magic directorial wand over this revival.

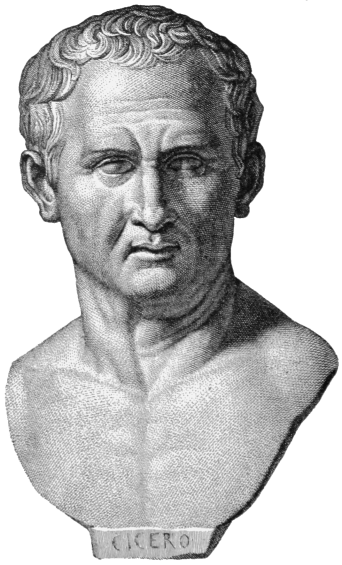

Copenhagen is not quite a perfect play. But it is so close that it barely matters. Mr Frayn is a very, very clever man. So naturally he takes a very, very big subject for Copenhagen. The is the imagined conversation between Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr in Nazi occupied Copenhagen during WWII about whether eminent nuclear physicists could or should attempt to prevent the building of a nuclear bomb. The exact circumstances of the meeting in 1941 are unclear from their writings, though Bohr seemed to react angrily to whatever Heisenberg brought to him, and there has been much subsequent debate, in part fuelled by MF’s play, about exactly what happened. Out of this admittedly dramatic conceit MF constructs a play of intense philosophical enquiry, offers us both a science and a history lesson, shows the loving and fraught relationships between the eminent Bohr (then 55), his wife and amanuensis Margarethe and his one time student Heisenberg (39), and. as if that wasn’t enough, reminds us of the tension between the “objective” universe around us and our “subjective” view of that world that our consciousness constructs.

The memories of the meeting between the two physicists are played out in various ways, three times “another draft”. Time is not linear. We see several versions of events. The protagonists do not always occupy the same time and place. It is not always clear if they are talking to each other or to us the audience. This “plot” and the movement of the actors mirrors the behaviour of atomic particles in Peter J Davison’s monochromatic set. Did Heisenberg come to warn Bohr and, by implication, the allies about the Nazi nuclear programme? Or did he just want approval from his mentor? Or was he fishing for technical information on what was needed to trigger the required chain reaction? Did Bohr put him off the scent? How fervent was Heisenberg’s patriotism? Or his morality? Was he oblivious to what his country was doing? Did he help the half-Jewish Bohr and Margarethe escape from Denmark? How “guilty” did the scientists feel when looking back and are they trying to assuage that guilt – it was Bohr who ended up in Los Alamos after all?

MF cleverly uses anecdotes and the past history of the three protagonists to draw parallels with the scientific concepts they discuss. Skiing and table tennis act as metaphors to contrast the two men’s characters and approaches to scientific enquiry as well as a way in to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle and Bohr’s complementarity principle. A pre-war train journey by Bohr shows how electron spin theory was disseminated across Europe and his movements mirror that of the particles he describes. A card game where Bohr bluffs by mistake points up the risk of nuclear proliferation. Toys and weapons are elided. The death by drowning of one of Bohr’s sons, Christian recurs as a motif for what might have happened if someone or something had intervened. (The video backdrop courtesy of Nina Dunn has a lot of waves, alluding to the drowning and presumably wave theory). There’s probably loads more I missed.

Even with these “simplifying” devices, (which, as the two scientists remind each other to revert to “plain” language for Margarethe’s sake, can sometimes patronise), this is dense stuff. But it doesn’t feel like it. Aside from one tiny slip, Paul Jesson as Bohr and, especially, Charles Edwards as Heisenberg, are utterly on top of the language, and Michael Blakemore’s direction ensures the delivery is perfectly placed. Patricia Hodge avoids smothering Margarethe with an overly haughty demeanour, protective of her husband and suspicious of Heisenberg, the nucleus revealing the human failings of both.

As I understand it, and I don’t, the Copenhagen Interpretation was proposed by Bohr and Heisenberg before the war as a way to reconcile different theories of quantum mechanics. Quantum mechanics can only predict the probabilities of what might happen in physical systems. The act of measurement affects the system to reduce to the one result that is observed. Like what MF is doing with the play. With us doing the measuring. Though we cannot be sure of the result.

Big ideas, and especially big scientific ideas, can often lead to big drama. But dramatists can often overreach themselves or retreat back into the human and not push us intellectually as hard as they should. Copenhagen, like Brecht’s Life of Galileo, doesn’t make that mistake. One of the best plays I have ever seen and, once fizzing, a near perfect production.