Luciano Berio: Theatre of the World

London Sinfonietta, Kings Place Choir, Jonathan Cross (presenter), John Woolrich (curator)

Kings Place, 4th November

- Lucy Schaufer – mezzo-soprano

Michael Cox – flute

Darragh Morgan – violin

Paul Silverthorne – viola

Timothy Lines – clarinet

Lucy Wakeford – harp

- Young violinists from Waltham Forest Music Service and the Kurumba Youth Orchestra

London Sinfonietta

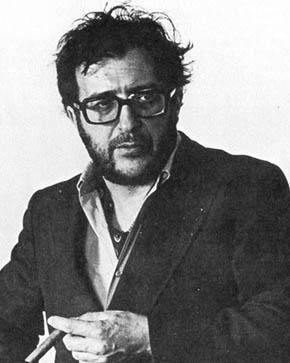

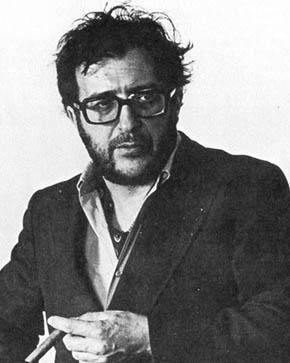

Luciano Berio

- Lepi Yuro

- E si fussi pisci for solo viola and for choir

- Duetti: Aldo

- Naturale

- Duetti: Various

- Divertimento

- Chamber Music for clarinet, cello, harp and mezzo-soprano

- Sequenza II for harp

- Autre fois

- Lied for clarinet

- Air arr John Woolrich

- Berceuse for Gyorgy Kurtag

- Sequenza I for flute

- Musica Leggera

- O King

- Chants Parallelles

Many years ago, maybe 30 or so, I heard a piece by Luciano Berio in a mixed programme at the Barbican. The ticket was free, courtesy of FF, and I cannot, for the life of me, remember the other pieces, the performers or the name of the Berio work. But I remember being completely blown away by the music, making a firm mental note that it was by Berio and that I should explore his music further.

Of course I didn’t. Modern classical music was just too tricky to grasp and I had a life to get on with. But there must have been the germ of something there. Now that I am older, and maybe wiser, I am beginning to understand that this was not a one-off novelty experience. There was something about Berio’s music that had left a mark. There seem to a handful of other modernist classical composers who similarly create a connection for me and I am still working my way through other candidates. Outside of the minimalists and a handful of contemporary names, Berio, along with Iannis Xenakis, Gyorgy Ligeti and Krzysztof Penderecki are the chaps that float my boat. There may be more.

So I am actively seeking out performances, live and recorded, of these lads. Heaven knows why they stand out but I think I am drawn to the fact that they all seem to engage with the musical past in some way, they pump up the rhythm, they can create extraordinary sound worlds (if you can’t hum it best to get wowed I find) and they favour dramatic and dynamic contrasts. No doubt if you know what you are talking about when it comes to music you would be able to offer me more comprehensive explanations (feel free to do so – I would be very grateful). There is still a lot of modern and contemporary classical music that leaves me absolutely baffled so there must be something going on in my head with these particular composers.

Here was a marvellous opportunity to enjoy a variety of Berio’s small scale output as part of the Turning Points series at Kings Place curated by British composer John Woolrich with the London Sinfonietta, who excel in modern works and premiered many of Berio’s pieces in the 1970s and 1980s. Now Mr Berio didn’t seem to suffer from any form of “composer’s block”. Prolific doesn’t begin to describe it. He composed for all manner of instrumental forces, including electronics and tape, and was particularly adept with the human voice, as well as strings, piano and flute Their are many large scale works, Coro and Sinfonia are maybe the most well known, but there is also a wide range of chamber and solo pieces which left Mr Woolrich with a serious curating challenge. One which I think he responded to with aplomb.

If there is one thing that characterises Berio’s oeuvre it is the way he incorporates the music of the past into the music of his present (the second half of the C20 to be exact). The references can be direct in terms of source material, (he arranged the work of diverse composers from Monteverdi to Mahler), or indirect in terms of fragments, quotes and styles. He saw this as transcription rather than collage but the effect, for the non-musical listener like me, is like a comfort blanket which anchors the “avant-grade” in the familiar.

Folk music played a large part in his framework and this concert kicked off with Lepi Yuro, a classic Croatian folk song scored here for viola. That was followed by a famous Sicilian folk song, E si fussi pisci, set first for solo viola and then, in its more usual format, for mixed chorus, with some suitably fishy impersonations at its conclusion. This choral arrangement was one of the very last pieces Berio composed. Nothing challenging here at all.

We then moved on to one of Berio’s short 34 duetti (1983) for two violins. These were originally written as teaching pieces to introduce the techniques of contemporary music to students, with one half of the duet given a much higher level of technical difficulty than its partner. Each was dedicated to a performer. composer or musicologist and, through time, they increased in sophistication as Berio took a playful view on the history of violin composition and just what it was possible to do with the instrument. The first piece was dedicated to Aldo Bennici, one of Berio’s favourite champions and a multiple dedicatee. After Naturale we were treated to ten more of the Duetti with Darragh Morgan, the LS’s lead violin, charmingly accompanied by young members of the Waltham Forest Music Service and Kurumba Youth Orchestra. Bartok, Stravinsky, Boulez and Berio’s Italian contemporary and sidekick in his electronic adventures, Bruno Maderna, were all name-checked.

Naturale from 1985 takes a recording of a raw and passionate Sicilian folk singer, Peppino Celano, belting out street vendor cries, (if you get the chance listen to Berio’s Cries of London for six unaccompanied voices which is just amazing), and frames it with an extremely expressive viola playing material transcribed from folk songs as well various percussion effects from marimba, rototoms and tam-tam. It is a extremely affecting and the most substantial piece on show in the programme.

Next up was Divertimento, an early piece from 1946 (revised in the mid 1980s) composed for string trio, before he went to the US and discovered serialism, and which pays homage to Stravinsky and Bartok. This was followed by the first of the two Sequenzas on show, this being No II for harp with No I for solo flute following later on in the programme. Berio’s 18 Sequenzas are amongst the most well known and performed of his compositions and are staples of the solo repertoire for the instruments they showcase. In each case they exploit, with Berio’s trademark humour and musical knowledge, the full gamut of playing possibility with extended techniques piled up high. Watching Lucky Wakeford thumping the side of her harp or picking up the very highest registers was a joy. Berio wanted to show just what was possible beyond pretty glissando for the harp and he surely does. This was also true for the more commonly encountered Sequenza for flute played by Michael Cox which was another highlight of the evening.

Autre fois from 1971, scored for harp, flute and clarinet, is a miniature subtitled Berceuse Canonique pour Igor Stravinsky, which tells you pretty much everything you need to know about its mood and structure. This was followed by Lied for solo clarinet (here played by Timothy Lines) which, as the title suggests, sounds like a mournful song. The orchestral version of Air dates from 1969 but the following year it was recast for soprano and piano quartet. Our mezzo-soprano for this evening was Lucy Shaufer who was in fine voice. Remember Mr Berio’s works for voice comprise some of the finest contemporary pieces for mezzo-soprano given his muse was the American Cathy Berberian whom he married in 1950 and whose professional partnership extended well beyond their divorce in 1964.

Air was followed by Berceuse per Gyorgy Kurtag, another short piece written in 1998 and dedicated to the redoubtable Hungarian master of the very small. This was followed by Musica Leggara (1974) for flute, viola and cello, (and I gather a tambourine if required), dedicated to a certain Godfreddo Petrassi, which is a spiky canon and not I think the “light music” of the title. Another joke maybe. The concert ended with one of Mr Berio’s most famous vocal pieces, O King, written in 1968 for mezzo soprano and here strings and woodwinds. This was later incorporated into Sinfonia, possibly Berio’s most influential work. This was written to commemorate the death of Martin Luther King and, as you might expect, packs a powerful emotional punch as the civil rights leader’s name gradually emerges from the soprano’s voice line, If you could pick one work that gets to the heart of Berio’s music this might be it.

i was, annoyingly unable to stick around for the post concert discussion, (I know this sort of thing smacks of obsessive nerdiness but you can learn a lot), but the insight into Berio from the interviews showing in the other Hall at Kings Place was very welcome. He didn’t sound like he was the easiest chap to get on with but the reminisces did show just how broad were his influences and how much he influenced. His role as a teacher and mentor and his fascination with the business of making music, with sound itself, was also emphasised.

And we got to listen to Chants Paralleles, one of his ground-breaking electronic works from 1975. Now a lot of this sort of thing is just so much electronic bubble and squeak in my very limited experience but once again, somehow, Berio makes it vital and intriguing.

There you have it. I am a fan. Give him a whirl. You never know you might like it

And hats off to Kings Place for these Turning Points events. There is a bit of cheesy novelty involved in some of them but this can be overlooked given the learning on offer. The concert on 24th March 2018, from the London Sinfonietta again, which brings together some classic chamber works from the early C20, and links this to space-time and Einstein, (if every playwright on the London stage seems to be intent on shoehorning in brain-bending science, why not music?), looks interesting. As does the OAE’s contrasting of Haydn’s first and last symphonies on the 12th May.

I don’t suppose the bigwigs at the Wigmore Hall are quaking in their boots but Kings Place has emerged as a worthy foil to the grand old dame of Wigmore Street.