A Midsummer Night’s Dream

English National Opera, 4th March 2018

Out of a long list of wildly inappropriate events that I dragged BD along to when she was younger perhaps provocateur Christopher Alden’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in this very house was the most egregious. Not because the 14 year old her wasn’t up to the task of taking some pleasure from Britten’s opera; she is a very clever young woman who makes me immensely proud, (as do the other two in the very unlikely event that they read this – “Dad, what exactly do you do with you day now you are no longer working”). No, it was because of the audacious sub-text of public school abuse which underpinned the production. Not that this wasn’t an interesting, and very valid, perspective, just that it maybe wasn’t quite the Dream we were expecting.

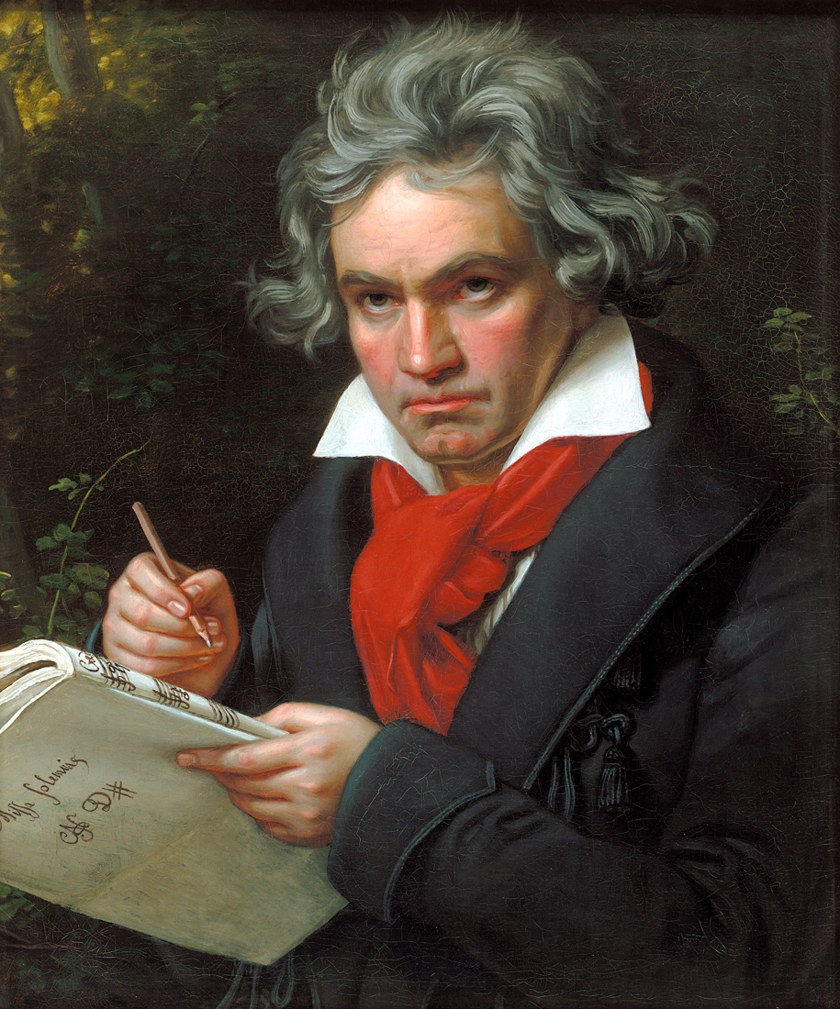

ENO has reverted then to the older, 1995, Robert Carsen production of AMND, last revived in 2004, to pull in the punters. Good for me because a) I haven’t seen it and b) it is brilliant. Now my regular reader will likely be aware that I struggle with a lot of opera. Monteverdi, some Baroque, Mozart and some C20, can work for me but it is by no means guaranteed. Contemporary opera is what usually really floats my boat. There is a special place for Britten though. This is because it is English, or more precisely was written in English, so I have half a chance of understanding the words with my dodgy ears and don’t have to flick eyes up and down to sur-titles. Moreover, there is a proper marriage between libretto and music. The music fits the words and the drama and not the other way round. Britten chose stories with real drama and assumed that all of his performers could act. This much is reiterated by the interview with Britten in the programme. I care about the voices but I am not smart enough to know just how good the singers really are. In contrast I can understand why an audience gets all juiced up when the Queen of the Night hits those F6’s in Der Holle Racht … but it doesn’t always make up for an unfunny Papageno, risible plot and all that crass symbolism.

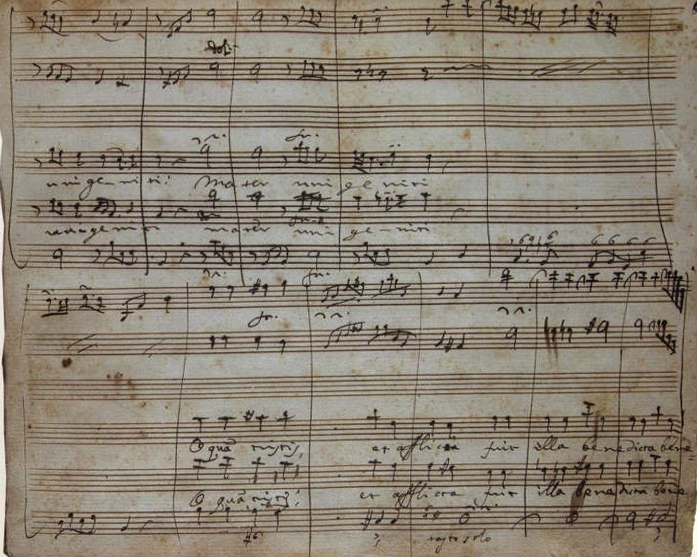

So drama first, music second, voices third. BB was judicious in his choice of source material, whether it be Auden, Crabbe, Maupassant, James, Melville or Mann. And why not turn to the greatest of them all in Shakespeare. But where to cut AMND, to avoid creating a 5 hour extravaganza, and how to shape the music around an already musical text? This is where BB, and Peter Pears, who took full joint credit for the libretto with BB, is so clever. By cutting out all the arranged marriage preamble, with the insertion of just one new line, we jump straight to the forest with Oberon and Titania wrangling. We swiftly get to experience the three different, but interlinked, sound worlds that BB has created for fairies, humans and mechanicals. The chop does mean that when Theseus and Hippolyta finally pitch up it’s a bit of a jolt, but by then we have had so many musically signposted episodes it’s easy enough to apprehend. A little bit of nipping and tucking in the order of the episodes to match text to music does also make for some novel juxtapositions: cheeky BB and PP send the lovers to bed unmarried, for example. Anyhow it’s the Dream so most of the audience will be up to speed on the story..

As ever with BB there a lot of essentially simple musical ideas which mean a numpty like me can feel the structure even if I can’t break the language. These ideas are clothed in innovative execution though. The Balinese influences, the debt to Purcell and Ravel, a bit of unthreatening twelve note serialism, all are audible, for this is the opera where Britten meshes the orchestral coloration and technical precociousness of the early operas and orchestral works with the spare stripped back austerity of his last decade or so. That is why, to me, it always sounds strikingly fresh and approachable whilst still endlessly inventive. The repetitions tell us where we are, and who we are with, in the drama but also allow us to soak up those exquisite sonorities that BB excelled in producing.

Intelligent and beautiful music in the service of the drama, not just a parade of flashy tunes. Which is where director Mr Carsen comes in, or more exactly his assistant, Emmanuele Bastet who supervised this revival. If Will S has provided plot and poetry, BB a crystalline musical structure around it, then the director only has to respond with a few big, bold ideas, and, ta-dah, success. Which is what we have here thanks in large part to Michael Levine’s outstanding designs.. A giant sloping bed fills the stage. Emerald green (Oberon) and a nocturnal blue (Tytania) dominate with occasional flashes of crimson. The Trinity Boys Choir of fairies marches on and off in perfect unison. The mechanicals, look like what they are, and their props in Pyramis and Thisbe, strike the right note of amateurish craft. The humans virginal white is gradually besmirched before they appear, alongside King and Queen, in glittering gold. There is coup de theatre in the suspended beds. Backdrops and lighting follow the same sharp, uncluttered aesthetic. A sort of synthesis of symbolist, minimalist and colour-field art, or maybe child-like Expressionism. Whatever, it it spot on. Any AMND, whether opera or on stage, that gets too floaty and ethereal gets the thumbs down in my book. That is not what dreams are made of.

Our Puck here, in the form of actor Miltos Yerolemou, counterpoints the action with his actions as much as his words. He is a very funny clown, (note he last appeared on stage as the Fool in the Royal Exchange Lear with Don Warrington), with pratfalls and tumbles a plenty, but he is the glue which brings the fairy and human worlds, fleetingly, together. As well as the superb design it is the choreography which enthrals in this production, courtesy of none other than Matthew Bourne and updated here by Daisy May Kemp.

Counter-tenor Christopher Ainslie stood out for me as Oberon, but that’s the way the opera is written, and because he is really, really good. The quartet of Hermia (Clare Presland), Lysander (David Webb), Helena (Eleanor Dennis) and Demetrius (Matthew Durkan) were well matched. The last three of these, along with our Tytania, soprano Soraya Mafi, and Theseus, Andri Bjorn Robertsson are all ENO home-grown talents, whose slight lack of projection was more than compensated by their movement and flair for the drama (and comedy). Joshua Bloom was perhaps an overly grandiloquent Bottom but that mattered less when unmasked/un-assed.

AMND doesn’t require a big orchestra which means ENO newcomer Alexander Snoddy, who is Director of the Nationaltheater Mannheim, could bring out all of BB’s eloquent phrasing and still keep the volume restrained enough to ensure the cast could all be clearly heard.

A perfect opera then based on a near perfect play near perfectly realised. At times like these I can accept, just, that opera trumps theatre as the greatest of art forms.