The Red Lion

Trafalgar Studios 2, 1st December 2017

Patrick Marber is a talented chap. Directing, adapting, writing screenplays, comedy material. Yet he is at his best when he writes original plays, or maybe even, as in this case, where he remakes his own texts. (Having said that his screenplay for Notes on a Scandal might be his finest work. Zoe Heller’s novel, Judi Dench, Cate Blanchett, Bill Nighy, Richard Eyre directing, a Philip Glass screenplay. Did the producers have pictures of the SO and I when they were discussing their ideal target demographic for this film?)

I didn’t get to see this at the National in 2015 so was delighted to see this relatively rapid revival, courtesy of Newcastle’s Live Theatre, turn up at the smaller space at Trafalgar Studios. I have to confess I am not the biggest fan of the TS generally, too many imprecise productions relying on cast name recognition to pull in the punters, too pricey and not the comfiest seating. Whilst the seating in TS2, at least where I was, is challenging, the value equation here was sound. It will be interesting to see what happens when the spaces are revamped as is the plan.

So, not knowing the play from first time round, I cannot be sure what Mr Marber has refined here to get it down to 90 minutes or so (from the original 150) but, whatever it was, it seems to have worked based on a quick perusal of the proper reviews this time vs last time. The TS2 stage, with a design by Patrick Connellan, certainly looks the part, a small, dank changing room, kitted out (literally) in perfect detail, you can practically smell the sweat, the grass, the mud, the liniment (actually you really can smell this), the aftershave. Those in the front row are in danger of being picked for next Saturday’s game they are that close. Patrick Marber based the play on his experiences as a director and saviour, with others, of non league Lewes FC, but anyone who has ever played the game at pretty much any level will know this place.

What Marber is able to do here, I gather more successfully than the original, is to use football as a metaphor for life, as so many writers have down in the past, but to avoid the cliche and melodrama that has cursed so many similar of these endeavours. The dialogue is still alive to the rhythms of football, and to the banality of its expression, and there is ruthless dissection of the ugly underbelly of the “beautiful” game. I am always struck by the romantic yet resigned mythologising, the “sporting ideal’ if you like, that some, otherwise rational, men of my acquaintance reserve for their football obsessions. The notion that this is just a very poorly managed branch of the entertainment industry, prone to the worst excesses of capitalist venality and institutional malfunction, just seems to pass them by.

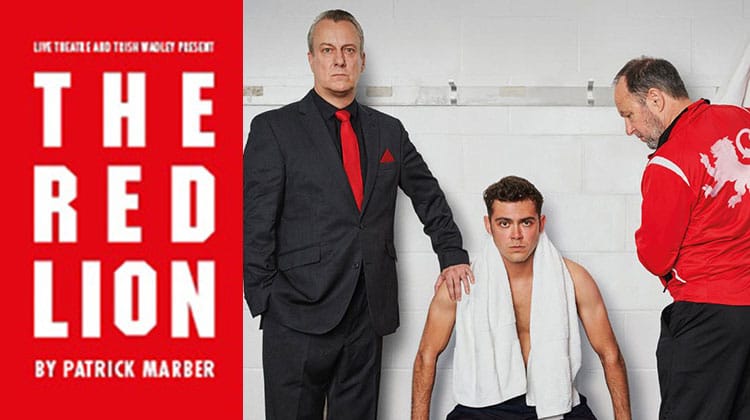

Marber probes these failings but also, as his wont, explores the complexity of male interaction. Trust and loyalty, hopes and dreams, betrayals and deceptions, bravado and vulnerability, all are displayed. Each of the three characters, Stephen Tompkinson’s desperate manager Kidd, John Bowler’s weary retainer Yates and Dean Bone’s talented youngster Jordan, are all flawed in some way, and have misplaced their moral compasses in the pursuit of footballing glory. All of them need to make grubby compromises in order to survive in the world they inhabit. Like I said metaphors abound.

Stephen Tompkinson always seems to bring out the emotional frailties of the men he plays and this is no exception. Kidd is living alone, divorced, broke. He is also a cynical bully, albeit weak and toothless. Football is all he has. It is the last minute of extra time and he needs a break. Jordan’s skill might just provide it. Jordan though harbours a secret beneath his apparent integrity. Dean Bone is on the ball from the opening whistle, asking what’s in it for him. Yates wants a piece of the glory, his own life having collapsed until the club offered a lifeline. He once lifted the trophies, now all he does is clean them. John Bowler’s lines benefit most I suspect from the relocation to the North East in this production. His body may be broken, but his mind, and his words, are sharp enough. Soon enough all three sense an opportunity, but all three are doomed to see it slide away, but cannot accept the blame for this lies within.

This may sound like an arduous slog. It is anything but. The moral tragedy is leavened with plenty of humour and, under the sure touch of director Max Roberts, the play rattles along to its conclusion (which may actually have been just a touch too rushed).

So a tightly orchestrated production of a now tightly drawn script with much to say about football, masculinity and life. Let us hope that Mr Marber can find another subject which spurs him to write another original play in the not too distant future. His talent requires it.