Billy Budd

Royal Opera House, 7th May 2019

The corruption of innocence, the struggle of good vs evil, Christ-like redemption and Pilate-like equivocation, the conflict between natural and legal justice, the outsider’s struggle for acceptance, repressed, scopophiliac, homosexual desire, the rational, scientific world contrasted with the mythic poetry of the imagination, dreams, the sea, the biblical musicality of his prose. Even the same initials. It isn’t much of a surprise than Benjamin Britten, who always fancied himself as a bit of a martyr, and his librettists EM Forster and Eric Crozier alighted on Herman Melville’s classic novella for operatic treatment.

Forster had long been an admirer of Britten’s music, (who wouldn’t be), but the idea only crystallised in 1948. Eric Crozier was brought in to provide the expert, though not always smooth, link between composer and novelist. The premiere of the original production, in four acts, appeared on this very stage on 1st December 1951, as part of the Festival of Britain celebrations. The revised two act version, with epilogue and prologue for Captain Vere alone, first appeared here in 1964 but it is 19 years since the ROH last staged it in a production directed by Francesca Zambello.

The last time I saw it was in 2012 at the ENO in the Expressionistic version served up by David Alden. In one of Dad’s more widely inappropriate attempts to get BD into opera she came along too. Smart-arse that she was, and is, the themes, even when concealed by Mr Alden’s somewhat wilful interpretation, didn’t evade her. Even under all that maritime lingo this isn’t subtle even when it is ambiguous.

Having witnessed director Deborah Warner’s way with BB in The Turn of the Screw many years ago at the Barbican and in the Death in Venice revival at the ENO in 2013, (with the SO who surprised herself with a favourable reaction), as well as Tansy Davies’ Between Worlds, I wasn’t going to miss this production originally seen in Rome and Madrid. For once the Tourist paid up to sit downstairs though for opera of this scale, ( a cast of over 20 and a chorus of 60), and quality at this venue it seemed like a bargain when compared too the kind of bonkers prices the ROH normally requires from punters for a prime perch. Lucky for me those prices are generally the norm for the very repertoire I can’t abide.

(I know that there are bargains to be found, I normally sit in them, but they are compromised. Up in the amphitheatre you might be forgiven for thinking you had travelled to Zone 2, for example, and at the back of the balcony boxes you might want to take a book).

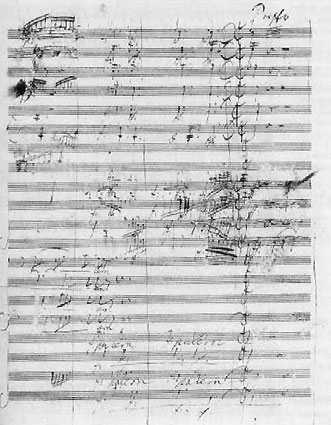

Billy Budd is BB’s grandest opera, in terms of music and ideas, but, self-evidently, it has one obvious constraint. Namely it is all blokes. BB is somewhat unfairly criticised for not serving up any top-drawer female roles. Ellen Orford, Miss Jessel in The Turn of the Screw, Tytania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Female Chorus and Lucretia in The Rape of Lucretia and, though I can’t be sure since I have never seen it, Queen Liz I in Gloriana, are all surely exceptions, but the fact is, perhaps unsurprisingly, it is in writing for the male voice where he excelled. In Billy Budd his cup overfloweth with the central trio of tenor (Captain Vere, the captain of The Indomitable), the bass of Master at Arms, John Claggart and the baritone of Billy himself. Then there are another fourteen named roles amongst the officers and the seaman, four boy treble midshipmen, the speaking only cabin boy and a singing chorus of 60, count ’em, augmented by another 30 actors. Put together the drama of the story and the opportunity to weave in traditional music, (including shanties,) with BB’s genius facility for word and scene painting in music and, wallop, you have, BB’s most powerful operatic score.

The orchestra doesn’t skimp on woodwind and brass, 4 flutes, 2 oboes, cor anglais, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, 2 bassoons, double bassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombone and tuba, and that’s before doubling up, or percussion, (though there are no “funny” tuned or untuned instruments smuggled in as in other works). So when conductor, here the reliable Ivor Bolton, orchestra and chorus are on song, as they were, especially that chorus under William Spaulding’s direction, then the director and principals have a strong base on which to build.

First decision for the director is whether to go full on 1797 or something more timeless. The former risks dialling up the salty procedurals in the scenes and libretto, the latter over-egging the psychological, parabolic, pudding. Deborah Warner has come out somewhere in the middle. The ROH chippies haven’t been beavering away creating a replica man of war. Instead the ship in Michael Levine’s design is conjured up from an immense skein of chains/ropes from which platforms, sails and hammocks, are suspended. This takes us above and below decks as required and leaves the chorus crew with, believable, work to do (choreography Kim Brandstrup). It’s brilliant. A near literal prison. Then again the rill of water front stage was maybe dispensable. The officer uniforms (costumes by Chloe Obolensky) are more mid C20 than late C18, with the crew in timeless sailor rags (albeit exquisitely tailored rags).

As with Death in Venice, the lighting design of Jean Kalman, (like the above, another of Ms Warner’s trusted collaborators), and Mike Gunning, (including that mist for the symbolic, unconsummated battle scene), is an integral part of Ms Warner’s vision. Billy Budd is not, even in the two act version, a hurried opera, rising and falling like the sea, (I may have got carried away here), to the key confrontations and confessionals. Deborah Warner’s allows some depth and breadth to emerge which maybe detracts from the required foul, claustrophobic atmosphere but brings the slippery themes, and overt symbolism, into focus. BB, whoever his collaborators, never allows moral certainty to emerge in his operas, that is why they are essentially so much better as theatre than most everything written in the previous century, (imagine Puccini or Wagner not melodramatically clunking you over the head every ten minutes – not possible see). Ms Warner wisely runs with BB’s uncertainty.

As usual the Tourist is not qualified to remark on the quality of the singing but, acting wise, Jacques Imbrailo as Billy himself stood out. Obvs he is good to look out, though not as much as Duncan Rock as Donald with his rippling abs, but he moves with complete naturalism and his Billy was “good” but never “simple”. And he certainly wrung some emotion out of his arias especially “the darbies”. Brindley Sherratt as Claggart, nails the giant credo, clear as a ship’s bell, and those inner demons, but could have been outwardly crueller. He is, as Ms Warner intended, an angel who is still falling, rather than full-on disciple of Satan. The still youthful looking Toby Spence’s De Vere does grow as the opera unfolds so that by the end, the “blessing” in the epilogue, he has us in the palm of his pious hand, but his remoteness in the first few scenes is disconcerting. I was also taken, again, with Thomas Olieman’s performance as Mr Redburn and Clive Bayley as the veteran Dansker.

Could you imagine a production that gets closer to some of the really dark questions about cruelty, sex, desire, exploitation and hierarchy that run counter to the narrative of atonement? Of course. Can I have a Billy who looks like who could deck and kill Claggart with one punch. Could there have been a little more “compartmentalisation” set wise to ensure the highlights in the score matched the action on stage? A bit more confusion and less exact choreography. Some sweat. blood and, look away now purists and families of Messers Forster and Crozier, some gratuitous swearing slipped in. A crew that really looked like they might eat the officers for breakfast. For sure.

On the other hand, in the literally overwhelming 34 chord sequence when Vere sentences Billy to death, in this production we stay with Billy and not Vere. And the three officers wordlessly damn him for hiding behind the legalese. Utterly brilliant. With that and other powerful memories I will happily take this production, until, hopefully, one comes along that really doesn’t hold back.