Marnie

English National Opera, The Coliseum, 3rd December 2017

I really don’t understand why the serious broadsheet reaction to Nico Muhly’s new opera has been so lukewarm. They generally seem to have admired the score, commended the ENO Orchestra’s playing under new Director Martyn Brabbins, praised many of the performers and, largely, looked favourably on the designs of Julian Crouch and 59 Productions (set and projection), Arianne Philips (costume), Kevin Adams (lighting) and choreography of Lynne Page. The criticism, as far as I can see, centres on the “histrionic” plot, though others think the story insufficiently tense, Nicholas Wright’s lean libretto, the unsympathetic characters, the structural stylisations and the absence of “memorable” arias.

Well I profoundly disagree with these criticisms. The operatic canon is littered with plots that are significantly more overblown than Marnie, yes the libretto is direct and lacks poetry, but this is a story of an unhappy woman who manipulates and is manipulated because of what happened to her, so the language seemed entirely appropriate to me. The libretto, together with the dramaturgical and visual rendering and the musical motifs, (each character has its own instrument, a shrill or seductive oboe for Marnie, disturbing trombones for Mark Rutland, a sordid trumpet for Terry), all made for a very clear and complete production. I don’t really understand why so many commentators look to empathise or sympathise with dramatic characters or demand redemption or recompense. Several flawed sh*ts on a stage does it for me.

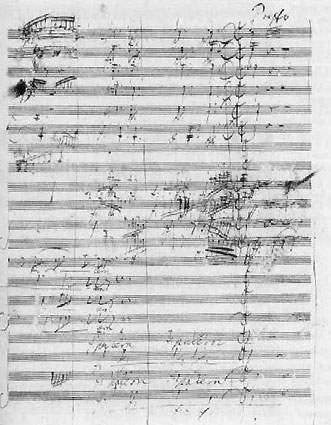

Finally for me opera usually fails, (as it so often does, though when it succeeds it can be the very best of art forms), because the singing takes over. Sounds perverse I know but when the voice of the fat lady is all the punters care about, to the detriment of plot, acting, movement, staging, ideas, drama, then I am out the door (not literally of course). This is probably why I seem to get on with the best of contemporary opera, and why I can leave, for example, Puccini to the buffs. Stories that make sense, music that matches the action, stuff to make you think. Nico Muhly’s music isn’t challenging, (though it is not entirely tonal), and does occasionally lapse into John Adamesque “romantic minimalist running on the spot”, but pretty soon a captivating new idea or sound pops up. This constant flow of musical phrases mirrors the constant flux of Marnie’s subconscious. His choral writing, (and the chorus here gets lots of action, and Greek style commentary), is sublime, up there with, well maybe not quite, Britten.

Messrs Muhly and Wright, at the suggestion of director Michael Mayer, have taken Winston Graham’s 1961 novel, which is written in the first person, as their source rather than Hitchcock’s 1964 film starring Tippi Hedren and Sean Connery. The latter relocates the story to the US, ramps up the saturated colours, echoes German expressionist films and has a vivid score courtesy of Bernard Hermann. This was the last time Hitchcock worked with Hermann, and with cinematographer Robert Burks, and the last of his disturbing “Hitchcock blonde” movies. So love it or hate it, it is, by the standards of today’s Hollywood, it is heady stuff. It is also in places quite different from the plot of the book.

I thought the setting in Home Counties Britain in the 1950’s and the closer adherence to the plot of the book, (with some tweaks, Terry is now Mark Rutland’s brother and Marnie’s phobia of the colour red is no longer explicit), made for a more interesting and less melodramatic story, without entirely losing the stylised “psychological terror” of the film. Hitchcock generates tension and unease through the way he directs and films as much as the plot itself. The opera was, perhaps, less able to generate this tension, (and cannot hope to draw out all of the dense action in the book), but it did make a better fist of showing why Marnie’s childhood traumas drove her to lie and steal. In particular the four altar ego Marnies which surrounded her at key moments, singing in close harmony, provided not only stunning visual images but also made flesh her inner turmoils. Similarly the eight male dancers, besuited and in natty trilbies provided an intriguing and restrained (most of the time) representation of Marnie’s fear of sex. Most importantly the ambiguity of the novel’s, and opera’s, ending is far more fitting.

American mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke as Marnie was cooly convincing, not only in terms of her singing, but also her acting, no need for any exaggerated, writhing around and screeching which is the operatic default button for “unhinged woman seductress”. Canadian Daniel Okulitch pulled off the remarkable feat of making Mark’s voice, as well as his character, become more disturbing as the scenes unfolded and his desire for Marnie escalated. Countertenor James Laing as Terry was my particular favourite however, a voice of immense clarity, a character of reptilian sleaze. Lesley Garrett as Mrs Rutland understandably owns the stage in every scenes she appears in. I could pretty much hear every word of every performer making this one of those rare occasions when sur-titles might be redundant.

Marnie is off to New York and the Met next and I reckon it will find other homes. For me this was up there with Thomas Ades’s The Exterminating Angel and George Benjamin’s Written on Skin in terms of contemporary operas that have thoroughly enveloped me. Marnie though, thanks to Mr Muhly’s musical immediacy and the equivocation of the story, is more approachable and interesting. If you have never been to a contemporary opera start here. Indeed if you have never been to an opera before start here. I bet you watch films with modernist scores, you might well like the theatre, and you will have heard people singing before. Those are the only qualifications you will need to enjoy this.