Academy of Ancient Music, Richard Egarr (harpsichord, director), Lucie Horsch (recorder)

Milton Court Concert Hall, 24th February 2019

- Antonio Vivaldi – Flautino Concerto in C major, RV443 (arr in G major for recorder)

- JS Bach – Harpsichord Concerto No 3 in D major BW V1054

- Giuseppe Sammartini – Recorder Concerto in F major

- JS Bach – ‘Erbame Dich’ from St Matthew Passion

- JS Bach – Oboe Concerto in D minor BWV1059r (arr for recorder)

- JS Bach – Concerto for Harpsichord No 7 in G minor BWV1058

- Antonio Vivaldi – Flute Concerto in G minor ‘La Notte’, Op 10 No 2 RV104

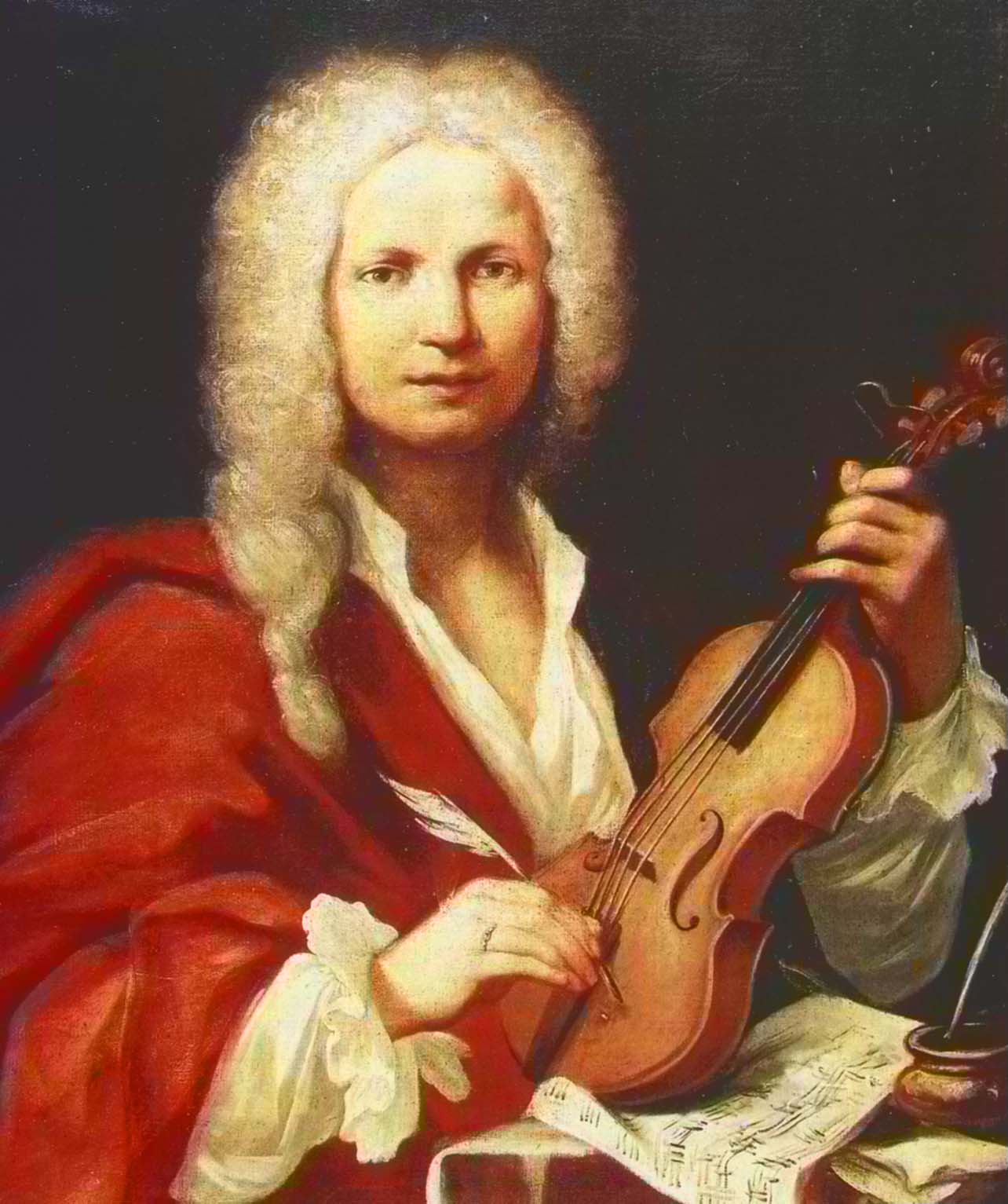

Lucie Horsch is just 19 years old. That’s her above, at 14 when she appeared in the Eurovision Young Musician festival. Her first recording of Vivaldi came when she was just 16. Now she may not be a household name outside the world of Baroque music and probably never will be given her choice of instrument, the recorder, but inside that select, (though I think widening), club she is a sensation. The recorder is a tricky instrument to play and to hear. Not in the lads of Ms Horsch. She is simply an astonishing musician. I haven’t heard anyone come close to the articulation, beauty, control and variation of sound that she achieves on these instruments. And her virtuosity in some of the faster passages on show in this concert was dazzling. Richard Egarr and the rest of the AAM, unsurprisingly, looked as pleased as punch throughout.

Now to be fair young Lucie started off with a few advantages. Mum and Dad are professional cellists, Dad with the Concetgebouw. Though perhaps this makes it more surprising that she stuck with the recorder, the “beginners” instrument. Mind you this beginner never even managed to master the basics, his music teacher quietly suggesting to his mother at age 10 that young Michael might want to stick to his books.

Anyway lucky for us that Ms Horsch decided she liked the sound and the immediacy of the connection between this “simple” instrument and performer. Of course the recorder doesn’t have too much in the way of “standard” repertoire beyond the Baroque and as the “pastoral”cue in early operas. There are a few Classical offerings and even one or two later works but generally there is none of the interminable showy sh*te from the Romantic and early C20. The technology of woodwind moved up a gear in the second half of the C18, the concerto became an ever blowsier conversation between soloist and orchestra and the textures of chamber music became more complex.

Go back in time though and it is time for the recorder to shine. Early and Renaissance music is brimful of the little fella, whether in instrumental ensembles or consorts, in dance music or as an accompaniment to voices. It is the Baroque though that shows the recorder at its most virtuosistic with the Vivaldi and Sammartini pieces on show here somewhere near the top of the pile. And this is not just one recorder. Ms Horsch is equally adept across the size range, sopranino, descant, treble and tenor. Mid C20, and some contemporary, composers have explored the unique sound of the instrument, technology has expanded the range and Baroque and earlier specialists are discovering new scores and arranging existing works, as here, for the humble recorder.

Vivaldi’s RV443 is just such an arrangement having been written for a flautino, though frankly it matters little since this is effectively the C17 version of the sopranino recorder. In this performance though the key was shifted down to the less stratospheric G major from the original C minor. This is the Baroque party piece for recorder (and piccolo) players with its lilting Largo monologue framed by showpiece brisk Allegro movements with dazzling solo parts. In the first movement the soloists chimes in with and unbroken string of 84 eighth notes! And that’s just for starters. The final movement calls for a seemingly never-ending run of triplets. Even by AV’s standards this is intoxicating stuff. He wrote a couple more concertos for flautino, RVs 444 and 445 as well as two specifically for recorder RVs 441 and 442. This though is the Daddy and there are literally billions of recordings HIP and not so HIP. I doubt I will hear a better live version that Lucie Horsch’s however. I have no idea where she gets the puff from.

The other Vivaldi concerto in this programme is also a staple. RV439 is one of the six flute concertos which make up ABV’s published Opus 10 from 1728/29. It was printed by the Roger firm in Amsterdam, which first brought out the Op 3 L’Estro Armonico, though a second version was also printed in Venice for recorder for which it will have likely been originally scored with a chamber accompaniment, 2 violins, bassoon and continuo, R10 4. This is explains its suite-like structure with six, blink and you’ll miss ’em, movements. La Notte is the night in Italian, hence the second title of the rapid second movement Fantasmi or ghosts, (though they seem quite playful spirits), and the slow fifth movement il Sonno, sleep. The first movement is a staccato affair, a sort of nodding off, the central Presto has a touch of the REM (dreams not band) flickers about it, and the finale turns very perky, showing off Ms Horsch’s skills to great effect.

Giuseppe Francesco Gaspare Melchiorre Baldassare Sammartini (1695-1750) was renowned in his lifetime as a wind performer, (musical not flatulist, a performance style I for one would like to see revived), notably the oboe, but I can also testify to the invention of his recorder concentre compositions of which this is by far the most well known. There may not be too much to distinguish the accompaniment but as a workout for the recorder player this is up there with Vivaldi, though with more variation and less reliance on repeated arpeggios and the like. Now we must be careful not to confuse Giuseppe with younger brother Giovanni, also a composer and oboist, who was one of the precursors of the galant Classical style, taught Gluck, counted JC Bach as a fan and influenced Haydn through his concert symphonies which are definitely worth a listen, (if only as musical history lessons). It helped the brothers that Dad was a professional French oboist.

Giuseppe wasn’t quite as forward thinking as little bro’ but there is still plenty to admire in his late Baroque/proto-Classical grooves. Outside of the concertos there is plenty of action for the recorder in his sonatas and trios. He kicked off his career in Milan but it took off when he moved to London and the court of Freddy Prince of Wales. Handel no less considered him the greatest oboist ever. (Note to the gammons. You see that those bloody foreigners have been coming over here and stealing your jobs for centuries. Musicians, composers, even the bloody royal family. Worth thinking about, should you ever choose to think, when you are humming the Hallelujah chorus. Actually scrub that. Most gammons in my limited experience couldn’t give a flying f*ck about classical music. Nor culture in general. One reason why they are always so bloody angry about everything especially the very Brexit they craved).

Or maybe they are angry because the Germans got all the best tunes. Well specifically Beethoven and JS Bach. Here were a few of them. Ms Horsch took a well deserved breather when Richard Egarr took centre stage, (actually this is when his harpsichord was moved side on), for a couple of JSB’s harpsichord concertos. In 1713 whilst working at the Weimar court you Bach was assigned the tasking of making keyboard transcriptions of some Italian concertos including 10 by Vivaldi himself. This was the wellspring from which much of his Italianate instrumental music emerged with the harpsichord concertos first performed in the 1730s at his weekly jams in Leipzig’s Collegium Musicum. These two started life as violin concertos and the original scores have no tempo markings. So nothing to stand in the way of Mr Egarr cranking up the rhythm and fiddling with his stops and couplers (don’t ask).

You probably know “Erbame dich” – Have mercy – from the St Matthew Passion with its violin lament supporting the singer’s teary plea to God. St Peter breaking down after his triple denial of Jesus. Here the instrumental version. led by Bojan Cicic’s expressive violin, was effective but lost a little bit by being taken out of context and “de-lyricised”.

So that just leaves JSB’s BWV 1059r. Now pay attention. This is the final one of the eight harpsichord concertos, a companion to nos 3 and 7 above. Except that this only survived as fragments so had to be reconstructed to create an oboe concerto. Utilising the two instrumental outer movements of BWV 35, the cantata Geist und Seele vird verwirret which have long passages of keyboard writing, which probably came from a concerto which might have been written for oboe. And some bars repurposed from another cantata BWV 156. Oh and the slow central movement of the three, (the first has no tempo guidance), is pilfered from an oboe concerto by Venetian composer Alessandro Marcello (also worth a listen) which JSB came across in his Weimar days, see above.

And here the oboe part was arranged for recorder. Confused? I’m not surprised. That’s what happens when composers have to churn out new works for money. Which JSB certainly had to do. No wonder he reused his back catalogue. And if we don’t have the original scores there is more room for interpretation and scholarship. Most of the harpsichord concertos started off somewhere else.

It matters here because this concerto, however arrived at, has some mighty fine riffs even by JSB’s standards. I didn’t know it at all. I liked it a lot, Which probably won’t come as a great surprise to you. As did my new companion, MSBDOB, newly returned to London and keen to hear some tip top playing. This was a fortuitous start methinks.

The beauty of the recorder sound is the connection between player and sound. There isn’t much between their breath and what hits your ears. This vulnerability and innocence, if you will, is also what makes it a sometimes awkward listen. In the best hands though, including these, it is a sublime experience. Lucie Horsch will surely get better with experience and when whatever tosser of a record company executive can no longer surround her with all that sexist, gamine, prodigy sh*te that the classical music world is riddled with.