Caroline, or Change

Hampstead Theatre, 18th April 2018

How many exceptions does it take before the rule is unproven?

I don’t, as a rule, like musicals, as I have oft repeated on these very pages. I absolutely adored this though. That might be because it isn’t your classic show tunes, jazz hands, fake emotion overload. It might be because Jeanine Tesori’s eclectic score ranges across the history of African-American music, (with help from Jewish American music, and plenty more besides), and reminds us how lost contemporary human culture would be without it. it might be because CoC is operatic in intent and form. It might be because it is through-composed with no awkward recitative exposition. It might be because it is formally inventive, what with its singing appliances, swinging moon (!), split level and revolving stage, courtesy of Fly Davies, and repeated metaphors. It might be because Tony Kushner is a playwright, and here book and lyric writer, of fierce intelligence, politically engaged, unafraid of tackling big issues, or incorporating his own, real, experiences into his work. It might be because Sharon D. Clarke is just about the most powerful actor to be seen anywhere on the British stage. There are moments in this where her entire body quivers under the weight of Black American history. And when she sings. OMG as the young’uns would have it. And she’s not the only one knocking it out the park. Abiona Omanua as Emmie runs her a pretty close second in her own way.

This production was praised to the skies on its original outing at Chichester. I believed the hype, but ummed and ahhed about booking for the Hampstead transfer, trying to rope in some chums. No takers, the SO didn’t bite, her aversion to musicals being ideologically sounder than mine, so I ended up taking the plunge on my tod. In the end it was probably more the urge to collect productions of Mr Kushner’s work that swung it rather than these reviews. At times I was engrossed by both Angels in America at the NT and IHO here at Hampstead even if, ten minutes later, I baulked at his indulgence. His translation of Mother Courage was also used in the so-so recent production of Mother Courage at Southwark Playhouse. I can see why he likes Brecht.

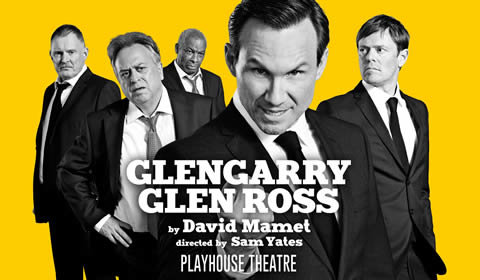

Well I only need to have paid attention to the 5* reviews, and so should you now that this is transferring to the Playhouse Theatre, from late November through to early February next year. I strongly recommend you get tickets. And don’t skimp. It is rubbish upstairs in the Playhouse and you need to take in all the set. I also see that the prices for decent seats, whilst not cheap, are not eye-gougingly expensive.

Music first. Jeanine Tesori’s score is magnificent. I assume it was composed for the orchestral forces on show in this production, 11 strong, with Nigel Lilley conducting. They are certainly put through their paces with Haydnesque chamber passages, a Jewish klezmer dance, hymns and folk tunes wedded to gospel, blues, soul, jazz and spirituals. And still room for a couple of show-tunes. If this all sounds a bit rich, it isn’t. The rhythms are simple and infectious and the melodies and motifs clear and recognisable even to this untrained ear. Ms Tesori doesn’t waste a note. What is most extraordinary is how she renders Tony Kushner’s text so immediately musical, as, presumably, he doesn’t write that way. There is a good interview in the programme, as there always is, from Will Mortimer of the Hampstead Theatre, with TK and JT where they describe their creative process. They seem to like working together. There is also an article written by TK setting out the genesis of CoC and a helpful essay on domestic workers in the US from slavery through the civil rights movement to the present day The HT programmes are always excellent in this regard, with material directly relevant to the production and not too removed or abstract as can sometimes be the case.

Whilst all of the orchestra sounded terrific to me I would highlight the brass and woodwind contributions of Alice Lee and John Graham. Their instruments were always likely to get the lion’s share of the expressive lines, given Mr Kushner is unafraid of emotion, but they sure know how to deliver them. In total I counted 53 songs. Like I say there is no filler, but you can work out for yourselves that, across the couple of hours of performances this means nothing outstays its welcome, so we have dynamism to match the musical invention.

So what’s it about? It is the 1960s in Lake Charles, Louisiana. It is hot and humid.. Caroline Thibodeaux is an African American mother of four kids, Emmie, whose consciousness is being raised by the Civil Rights protests, Jackie and Joe (I am really sorry I don’t know which young actors where in the hotseat on the day of the performance I attended), and an elder son in the army. Caroline’s drunk, abusive husband is long gone. She works as maid to the Gellman family, Stuart Gellman, his second wife Rose Stopnick Gellman, and young Noah (based on Tony Kushner himself). We also get to meet Caroline’s friend Dotty Moffett, trying to “better herself” through night school, and the Gellman grandparents and Grandpa Stopnick, in various imagined scenes, and when they visit Louisiana from New York.

Oh and we are introduced to a singing washing machine, a dryer, a Supremes style trio representing the radio, a moon on a swing and a bus. As you do. These fantasy elements make perfect sense in the context of the story Kushner and Tesori are telling, and provide further contrasts to the already rich mix created by Ms Tesori’s music and by Mr Kushner’s sharp, poetic, lyrical, emotional, analytical, metaphysical and often very funny lyrics. One detail in particular, the illuminated red ring around Ako Mitchell’s neck, to simulate the dryer, but suggesting something way more horrific from America’s past, shows just how many ideas are at work here.

In 1963 self-absorbed Noah is 8, (sorry, as with the boys, I can’t be sure who played Noah), and prone to bothering Caroline, and lighting her cigarettes, as she launders in the Gellman house basement. Noah’s mum recently died of cancer and the relationship with step-mum is delicate. Stuart, still grieving, and Rose’s relationship isn’t perfect either. Caroline gets paid $30 a week. Rose offers her food rather than a raise, and later, condescendingly suggests she take the small change the family leave in their pockets, especially Noah. This idea of change, (both personal for Caroline, and politically for her family and community), and of the unequal economic relationship between the Gellmans and Caroline, of which they are all acutely conscious, is central to the drama, and presents an extraordinarily powerful metaphor.

The assassination of JFK, and his legacy, and the destruction of a statue of a Confederate soldier at the local Lake Charles courthouse, provide wider social and political context and, in the case of the latter, acute contemporary resonance, given, for example, the ugly events last year in Charlottesville. The politics ramps up before, during and after the Chanukah party in the first half of Act 2, which, for me, served up half an hour of the most vital theatre I have seen ever seen anywhere. The aftermath of the party, and an elusive $20 bill, prompts a bust up between Caroline and Noah and then some sort of spiritual epiphany for Caroline, culminating in the passionate song Lot’s Wife, which made me, and half the audience, quietly blu. Emmie though has the last, defiant, word.

Caroline is angry, sullen and resentful at the hand that life has dealt her, but her faith, her dignity, her conditioning and the stark fact that she needs to feed her family, means she cannot fight back. Emmie, from the next generation, can though. Mr Kushner points out in the programme how damaging the failure to resolve issues of race and poverty has been to the American politic, but he also offers a message than change is still possible.

The Hampstead stage is just about big enough to contain the set, though I gather it was more expansive at Chichester, but small enough to let us savour every line and note. I don’t think I missed a word and Michael Longhurst’s direction was exemplary (if you’ve see Amadeus at the National you’ll know what he’s about), ably assisted by Ann Yee’s intricate choreography.

In my own little fantasy world of reviews on this blog site I dole out stars like candy, largely because I get so excited with how much marvellous culture London offers that I really do feel like I am in the proverbial sweet shop. This though is a brook no argument 5* masterpiece.

The best thing I have seen this year. And I was perched up in the gods wishing I was much closer and had booked sooner.

You must see it.