Britten Sinfonia, Thomas Ades (conductor), Nicholas Hodges (piano), Joshua Bloom (bass)

Barbican Hall, 22nd and 24th May 2018

- Beethoven – Symphony No 4 in B flat major Op 60

- Gerard Barry – Piano Concerto

- Beethoven – Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67

- Gerard Barry – The Conquest of Ireland

- Beethoven – Symphony No 6 in F major Pastoral Op 68

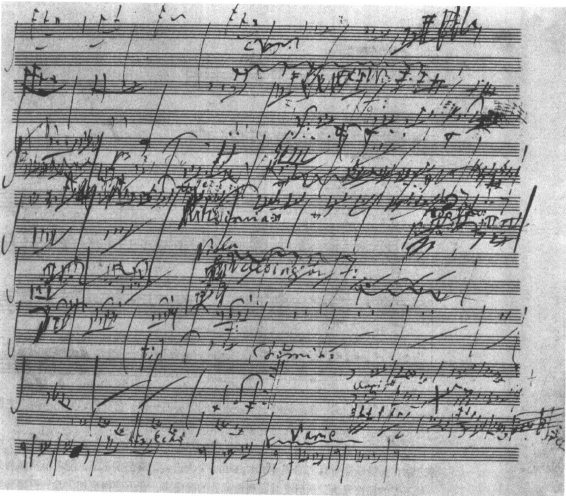

The latest instalments of the Britten Sinfonia’s Beethoven cycle under the baron of Thomas Ades, (alongside the valuable accompanying survey of Gerard Barry large-scale compositions) ,was as superb os the two concerts last year. (Britten Sinfonia and Thomas Ades at the Barbican Hall *****) (Britten Sinfonia and Thomas Ades at the Barbican Hall *****). That Mr Ades, and his friend Mr Barry, adore the music of Beethoven was never in doubt. That Mr Ades understands it, and can conjure up performances of the symphony that are as good as any that I have ever heard, is what makes this cycle unmissable in my view. I urge you, no I beg you, to come along to the final concerts next year of the last three symphonies. The Hall was no more than half full which is near criminal. If Gustavo Dudamel and his well upholstered LA Phil can fill the house with a big, if not particularly insightful, version of the Choral Symphony, then the Britten Sinfonia and Thomas Ades deserve at least the same. If you hate all the bombast that others bring to Beethoven please look no further: conductor and orchestra have binned all that sickly vibrato, endless repeats, glum grandiosity, and started afresh.

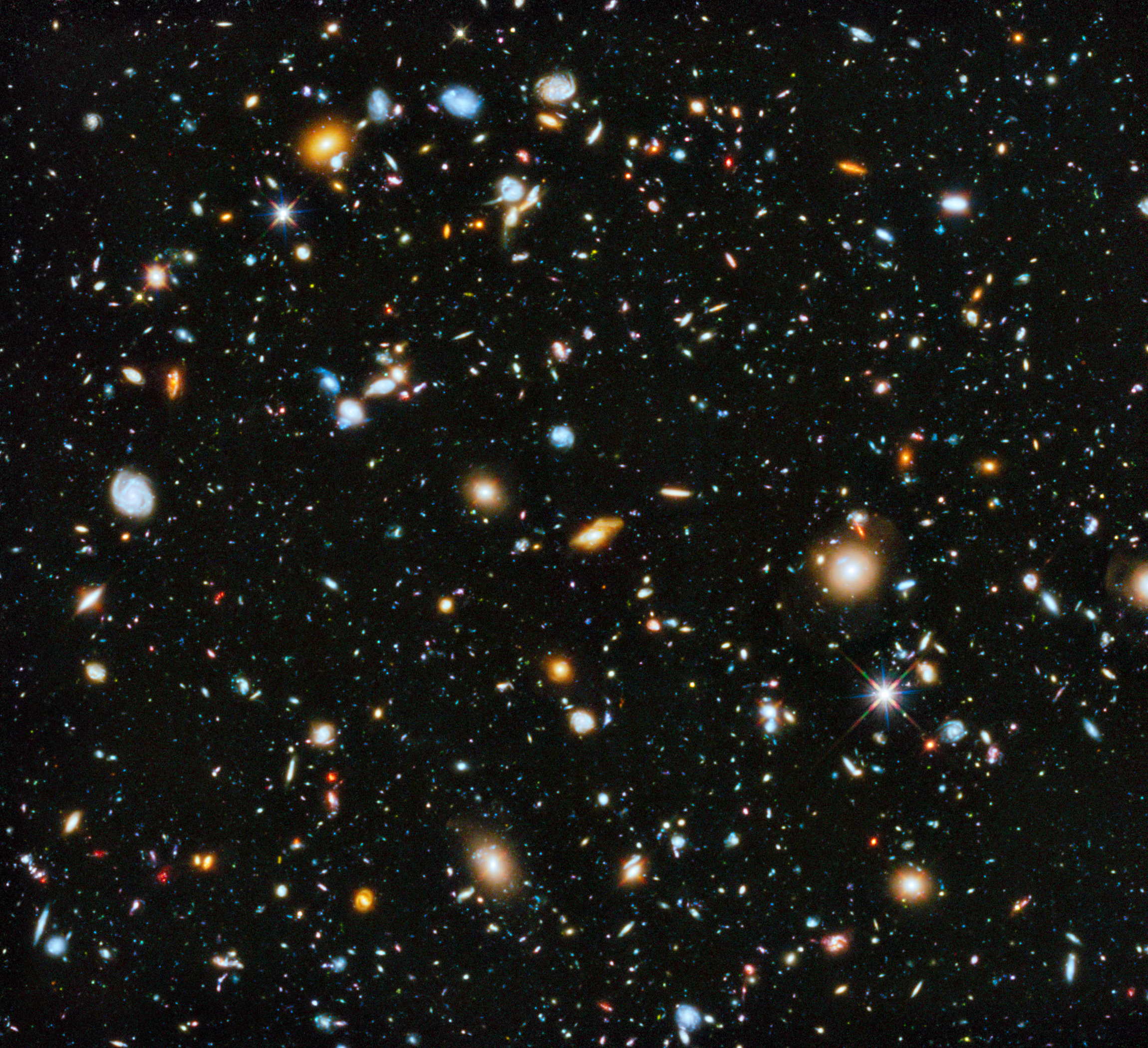

If you can’t go then look out for the recording of the cycle which should appear,God and finance willing. This is how Beethoven should sound. The right orchestral forces, the right tempi, to my ears at least, every detail revealed, and every detail in exactly the right place. Strings never thick and slushy, woodwind given enough room to breathe, brass precise, timpani rock hard. It is the difference between the way you might see an Old Master, badly hung, in the wrong room, of some C19 artistic mausoleum, centuries of filth accumulated on varnish, cracked, colours faded, and the way you might see the same work, restored rehung, with space and light aplenty, and notes which illuminate not patronise. The joy of rediscovery. The difference between a mediocre and a great performance in a concert hall is easily to tell even if you know nothing about the music. The audience will be still and silent. Sometimes though there is something more, a connection between music, performer and audience that fills the very air.

I felt this here. Or maybe it was just there were fewer people with more invested in the performance. Either way it was a triumph. The Fourth, like the Second last year, couldn’t be dismissed as a happy-go-lucky, lithe cousin of the muscular, growling, Eroica hero that they sandwich. The first movement, marked Adagio-Allegro vivace, is, for my money, one of the finest passages of music Beethoven ever wrote. The painful opening, the booming timpani and giant string chords which conclude it, the uneasy Adagio which follows punctuated by more big chords, the double repeated scherzo theme, a dance but with something lurking in the woodshed, and then the perpetuum mobile finale, which is almost too jolly. Indeed Beethoven scores it that way, a palpable sense of anxiety pervades the whole symphony. It needs a conductor alive to the Goth inside the symphony’s Pop, and its subtleties cannot contemplate too big a sound. Mr Ades is that man. The slow movement Adagio was, and I didn’t expect to use this word about these interpretations, sublime.

I get why 2, 4 and 8 are see as lightweights compared to 3, 5, 7 and 9, the keys, the structures, the moods, the context, but I think it is a shame to get caught up in this convention. The Fourth symphony in particular is as great as its more famous peers. So how would this conductor and the BS render the Fifth anew. Remember the Fifth, (once it got over the infamous disastrous first night, alongside the Sixth, and a whole bunch of other stuff), changed the face of Western art music. Composer, and the performer from now on could be Artists. Everything would be bigger. More emotional. More, well, Romantic. Audience and commentators were now at liberty to hear, think and write all manner of the over the top guff about “serious” music. For that we should probably throttle LvB but the Fifth is just so extraordinary, however many times you hear it, that we’ll permit him the excess.

I expected the BS and Thomas Ades to absolutely nail this and they did. Familiarity can breed contempt. Or it can, as here, promote shared understanding. Everyone on and off stage was able to revel in Beethoven’s astounding invention. If I ever hear a better interpretation I’ll be as a happy a man as I was here. The opening allegro, four notes, infinitely varied, needs no introduction, tee hee, it being the most famous introduction to a piece of music ever. I suppose some might tire of the repetition. Not me. Especially with no unnecessary repeat. The double variation of the Andante, which fits perfectly together ying and yang style, was ever so slightly less impressive but the Scherzo and the magnificent finale were glorious. As in the prior performances you hear everything, no detail is obscured, nothing is too loud or two soft. This means that, along with the “classical-modern” sound of the BS and the “right” calls on repeats that the architecture of Beethoven’s creation is fully revealed, from micro to macro scale.

With Mr Ades and the BS having nailed the detail, shape and rhythm of the symphonies to date, I wondered how they would cope with the Pastoral. Maybe this, with its plain programmatic elements, wrapped its more gentle cloak, expressing all that utopian, Arcadian, rural idyll fluff that art conjured up as a salve to assuage guilt about industrialisation and urbanisation, would be the symphony where Mr Ades’s precise, vigorous approach might come unstuck.

Nope. For choice this might have been marginally less exciting than the rest of the cycle, the precision and heightened differentiation between instruments robbing a little of the warmth from LvB’s narrative. I’ll take the trade though when it results, for example, in the most thrilling storm I have ever heard, double basses thrumming, timpani thwacking. It also means the opening Allegro, which can doodle on a bit, saw variety emerge from the repetition. Nature untroubled by Man. Messaien would have purred at the birdsong emerging from woodwind in the Andante. And, in the finale, we heard the relief of real shepherds, not a bunch of embarrassed house servants dolled up by their lords and masters. Most Romantic plastic art is as schmaltzy as the Neo-Classical flummery that proceeded it, but there is some which sees the world for what it is, not want artist and patron wanted it to be. And some of it, Constable, in his sketches and watercolours, and, in his own darker way, Goya, could eschew history, violent nature and dramatic landscape, and showed more of the working reality of rural life. This Pastoral was in a similar vein. I now this all sounds like a load of poncey bollocks, but hopefully you get the gist.

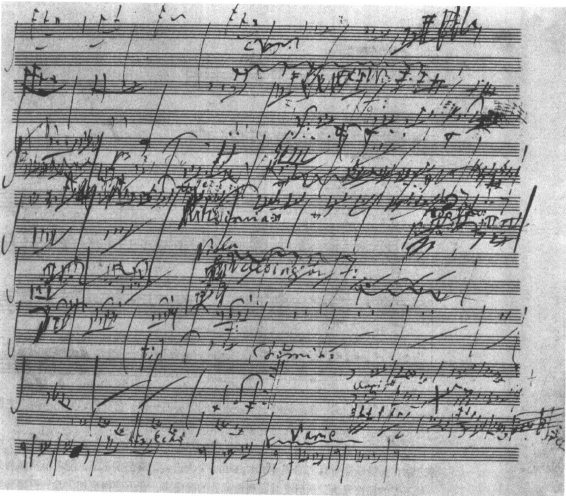

Moving on. You remember those nights out in the pub, with your mates, talking sh*te and putting the world to rights. Of course you don’t. You were hammered. But you do remember it was a bloody good night out and things might have got a bit raucous and out of hand. Argument and love. Well Gerard Barry’s Piano Concerto, here receiving its London premiere, is the musical equivalent of one of those nights. Nicholas Hodges was basically asked to man-handle, (at one point literally, playing with his forearms), the piano and to get into a scrap with the orchestra. As the punches swung it got funnier though 20 minutes was probably enough. Some of the piano passages were more conciliatory but only in the way a drunk bloke (the woodwind) tries to calm his even more drunk mate (the brass) down a bit. It ends with some childish tinkles. It isn’t in Romantic concerto form, played straight through with no obvious structure, it has two wind machines, (here not amplified as expected, a shame), there is no real interplay between orchestra and soloist, just opposition, it is abrasive, chromatic and gets pretty loud. I reckon Vivaldi might have come up with something like this if he were around today.

In short it is a piece of music by Gerard Barry. I am sure he is nothing like this is reality, and I am being borderline xenophobic, but I see him as the musical equivalent of Samuel Beckett, the very definition of cussed. I am going to have to find a way into recordings of his music, probably after this time next year, as it is just too funny and punk to ignore. Mr Hodges is an expert in this dynamic modernism, having recording and performed the likes of Birtwhistle, Rihm, Carter and, indeed, Thomas Ades himself.

Mind you if I thought the Piano Concerto was a bit in-yer-face bonkers I was in for an even bigger surprise with The Conquest of Ireland. This is set to a text from Expugnatio Hibernica by Giraldus Cambrinus translated by A. Scott and F.X. Martin. Cambrinus was a Welsh writer and cleric in the twelfth century who hooked up with the army which invaded Ireland. The piece is marked quaver = 192 which I gather is pretty enthusiastic but Mr Barry then marks it “frenetic” and “NOT SLOWER” just in case we missed it. The brave soloist, here Joshua Bloom, is nominally a bass but he gets up to all sorts of pyrotechnics as he sings/speaks/growls/squawks the entirely unmusical words. It is basically detailed descriptions, written in a somewhat pompous style, of the bearing and appearance of seven Welsh soldiers. There is just one short throw-away line which dismisses the native Irish as barbarians. Mr Barry has composed intense, passionate, exuberant music to contrast this prosaic prose (!). Bass clarinet, marimba, winds and brass in combination, percussion, all got a work out. It is sardonic, in the way that I now see that so much of Mr Barry’s music is, but it certainly provokes a reaction and makes you think.

Anyway back to the performers. The Britten Sinfonia are my favourite musical ensemble. The others I regularly get to see, the LSO, the LPO, London Sinfonietta, the AAM and the OAE, are all, of course, excellent, and there are international orchestras that can blow my socks off when they visit, but it is the BS which consistently educates and surprises me. And Thomas Ades, IMHO, is now the closest thing to the immortal Benjamin Britten, that I can think of. Composer, performer, conductor. Equally gifted.

Oh and a final plea. This time to the ROH or ENO. A Fidelio. With Thomas Ades conducting. And Simon McBurney directing. I’ll wait.