Philharmonia Orchestra, Esa-Pekka Salonen (conductor), Richard Watkins (horn), Allan Clayton (tenor)

Royal Festival Hall, 16th January 2020

- Carl Maria von Weber – Overture Der Freischütz

- Mark-Anthony Turnage – Horn Concerto (Towards Alba)

- Benjamin Britten – Serenade for tenor, horn & strings

- Richard Strauss – Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche

Broke the golden rule. It is bad enough that I inflict this shite upon you and join all the other narcissists clogging up the Interweb and generally adding to the carbon burden. But I had resolved not to comment on anything that I had not sat all the way through. Notes for my own consumption but never yours. Here though I felt compelled to announce just how marvellous a concert this was. Despite walking out after the Britten Serenade and thereby avoiding the Strauss. Which, as it happens, I have heard live a couple of times and loathed. Another bloke in the lift on the way down adopted the same strategy. Why sully the perfect?

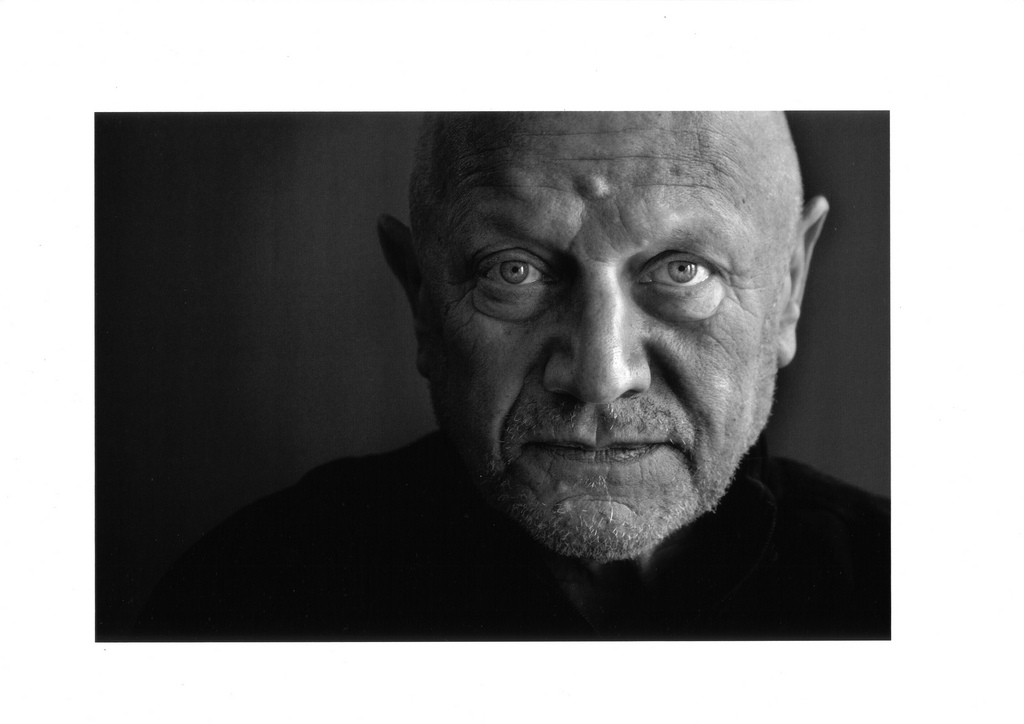

For I cannot imagine much better that this take on one of BB’s most sublime, and rightly popular, compositions. Comparable with the composers own versions surely. I might have guessed that Allan Clayton’s tenor is the perfect instrument for the work but how good is that Richard Watkins. He used to be principal horn for the PO, so he was surrounded by plenty of mates and presumably was attuned to Esa-Pekka’s no messing, forceful take on the work, even if he left before the Finnish maestro came to London. (Apparently E-P S, to add to his many talents, is a dab hand himself on the horn). He now works as a soloist fronting the London Winds and is a member of the Nash Ensemble. Every note was delivered exactly as I imagined BB composed it for the mercurial talent of Dennis Brain, the orchestra’s first principal player. The horn, let’s face it, when it enters its expanded harmonic world, is about the most thrilling, note for note, instrument in the orchestra. Obvs you can have too much of a good thing, but not here.

Which makes Mark-A T’s achievement in this world premiere of his own Horn Concerto that much more remarkable. He has always created contemporary classic music of real immediacy, but here, commissioned by Richard Watkins himself, he channels the German romantic horn tradition, of which Weber was a part, through the horn tributes of the English composing generation prior to him, Tippett, Colin Matthews, Oliver Knussen, and of course Britten himself, whilst still keeping his trademark jazzy syncopations and Stravinskian rhythms. BB’s piece, doh, is a paean to the night, setting those exquisite English texts through the ages, to faultless musical ideas, concentrated and not as flashy as some of his stuff. M-A T, in contrast, is all about the sunrise and the coming day. Alba in olde English meant “a call to the end of the night and beginning of the day”.

The so titled brief opening movement has lots of chirpy orchestral lines bouncing off the horn but, never thickens or overwhelms. The slow second movement is inspired by a late Larkin poem, Aubade, a morning serenade, in which the fear of mortality engendered by sleepless nights is banished by the light and the normality of the working day. The horn is the lyrical and bluesy expressive voice set against some beautiful, lower resister, string writing, punctuated with sustained low pedal points. The finale is also drawn from a poem, John Donne’s The Sun Rising, exactly the poet you want to mirror BB’s own choices, and does exactly what it says on the tin. M-A T offers up dense, chromatic, contrapuntal chords over which the horn soars.

Can’t remember the Weber and, like I say, no interest in the Strauss. But this was sublime and I expect Towards Alba to provide plenty of work for Mr Watkins, and others, in years to come. A fitting tribute maybe to another brilliant exponent of the French horn, Australian Barry Tuckwell, who sadly passed away on this very evening. I see Messrs Watkins and Clayton have recorded BB’s Serenade with the Aldeburgh Strings. Time to buy I think and set alongside BB’s own recording which featured Mr Tuckwell on peerless form and Peter Pears, later on his career, was marginally less the mannered English toff.