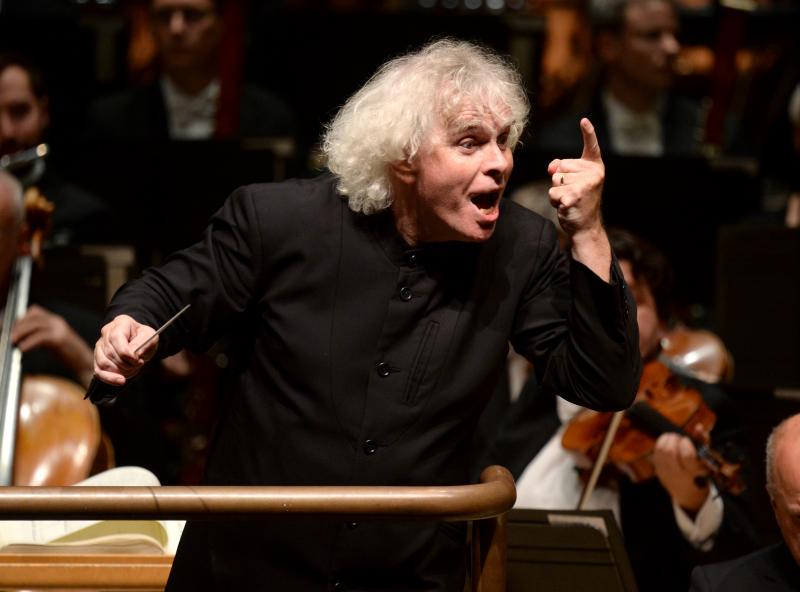

London Symphony Orchestra, Gianandrea Noseda, Yefim Bronfman (piano)

Barbican Hall, 3rd June 2018

- Ravel – Rapsodie Espagnole

- Beethoven – Piano Concerto No 3

- Mussorgsky arranged Ravel – Pictures at an Exhibition

It has been a few years since I have heard Pictures at an Exhibition live, and I have thoroughly enjoyed Mr Noseda’s way with Shostakovich and Beethoven recently, so I reasoned now was the time to reacquaint myself. Moreover Mr Bronfman’s account of the PC 4 last year, admittedly under the exacting eye and ear of Mariss Jansons and the Bavarian RSO, was pleasurable enough if not earth-shattering (Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican review *****). And I thought it right to risk another chapter in my ongoing love/hate relationship with Ravel.

The Rapsodie espagnole is a pastiche, of sorts, of Spanish music, in contrast to the rather more rooted offerings of the likes of de Falla, Albeniz and Granados, though Ravel is not the only French composer to have been seduced by all that sultry dance. Indeed when this was composed, in 1907, Maurice was immersed in all things Iberian what with his opera L’heure espagnole and the songs of the Vocalise-Etude. And his particular favourite was that familiar habanera rhythm – which turned into, amongst other things, the cha cha cha we now today. Mind you his mum was Spanish and he was born just over the border in the Pyrenees so it was in the genes/memes.

This was Ravel’s breakthrough orchestra piece and actually pretty much his only full force work that didn’t start in another form or from the piano. Whilst it isn’t based on any specific Spanish melodies there is no doubting where you are. Ravel, of course, was the master of musical and emotional coloration. Yet he doesn’t always surprise. When he does, for me mainly in the chamber, piano and piano concerto works, he can dazzle. When he doesn’t, often as not for me in the vocal works, he can be just a bit too diddly to no purpose. Not as diddly as Debussy who mostly really tries my patience, but still a triumph of style over substance.

Overall, given the material, this was reasonably enjoyable though I wouldn’t seek it out. There is a distinct descending four note ostinato motif that recurs through three of the four sections, with the Habanera being the exception. This helps it all hang together. The LSO was on top of the score, of course, but Mr Noseda’s reading felt a little forced, but not unpleasantly so, until the final Feria where the band cut loose.

This spilled over into the Beethoven where the quiet string theme that opens the C minor concerto shuffled into, rather than glided into, the room to set up the extended orchestral intro of the Allegro. Last time round in Beethoven I felt Mr Bronfman’s precise, delicate playing meant he got a bit bullied by the orchestra. I feared a repeat. As it turned out he was given enough room to breathe and the LSO, especially in the woodwind and lower strings, was on top form, with the Largo the standout. I have heard more convincing overall interpretations, and a bit more whoosh in the Rondo, but this was satisfying enough.

Hendrix, Morrison, Cobain, Vicious, Bonham, Curtis, Johnson, Buckley (x2), Cooke, Gaye, Coltrane, Parker, Parsons, Bolan, Tosh, Lynott, Nelson (PR). Some of my musical “heroes’ who died of unnatural causes, often with a fair bit more left to give, But if you want real rock’n’roll, nearly a century before any of these punters were doing their thing, then Modest Mussorgsky is your man. Obviously, like so many of the above, he was a f*cking idiot to waste his talent mashed up on booze, but, having chosen this course, and he did choose it seeking artistic freedom in this “bohemian life”, he got properly stuck in. Which meant he failed to complete vast swathes of work and didn’t get much beyond the piano and a bunch of songs and the completed opera Boris Godunov. He was a rubbish musician barely caring or knowing about structure or texture but boy could he capture a mood. and in BG he basically captures the essence of Russia.

Anyway there he is above in close up, in Repin’s famous portrait from 1881, which appeared in the marvellous Russia and the Arts collection at the National Portrait Gallery a couple of years ago. He looks a bit rough for sure. Worse still when you realise he was just 42 and died a few weeks later.

Easy to see what the colourist Ravel, as many others have done subsequently, was smitten with MM’s big ideas and couldn’t resist the temptation to smooth off the rough edges. The original piano suite of Pictures at an Exhibition was inspired by a posthumous retrospective of the work of artist Victor Hartmann, MMs mate who died aged 39. Mind you MM’s musical images, as you might expect, went way beyond whatever Hartmann envisioned, but the concept of the exhibition, with the repeated Promenade being us the viewer, holds the whole thing together and adds an ironic, detached air to the bombast. On the piano it doesn’t entirely work but in Ravel’s hands something magical emerges. Ravel used Rimsky-Korsakov’s edition of the piano original so a few changes were made but you get the feeling that MM would have been happy with the result even if he may not have known how Ravel got there.

It might all be very familiar but it the right hands, and the LSO and Gianandrea were the right hands, it can still be thrilling. Bydio, Baba-Yage and the Great Gate of Kiev didn’t disappoint. Boom. If you are a classical virgin and want to find a way into live performance there is no better way. You won’t stay there as you move on, and you may end up thinking it is all a bit daft, but the hairs on the back of your neck will still stand on end whenever you return to it.

Rock’n’roll. Sort of.