Another Kind of Life: Photography at the Margins

Barbican Art Gallery, 29th March 2018

I am lucky I have the time to visit popular galleries at quieter times. For there are some which, by dint of the material they are presenting, seem to get extremely busy at certain times. There are often queues round the block, (well not quite), of pensioners for the blockbuster exhibitions at the National, and similarly at the Tates, albeit with a more varied demographic. Good to see, if not good for seeing once you’re in.

The Barbican similarly attracts a crowd but here it is much younger and hipper. To stop myself harrumphing when they get in my way, or fiddle with their phones, and to avoid the embarrassment of being stared at given my tramp-like appearance, I find it best to go early before the layabout students are up or late when they are planning their evening’s entertainment.

Seriously though the Barbican curating team seems to be doing something right. Whilst it would be impossible to match the impact of the Basquiat spectacular (Basquiat exhibition at the Barbican review **) which I swear I tried to like but couldn’t, this new collection seems to be packing them in.

Photography, for me, is a less interesting artistic medium than, say paint, but when it shines a bright light on society, as here, than I can get drawn in. The curators have pulled together the work of, I counted, 20 photographers in total, who have documented people who have chosen to live at the margins, or right outside, mainstream society, either because of, or to reinforce, their individual, or collective, identities. The exhibition is careful to explore this theme across cultures and time. I knew next to nothing about any of the artists (bar Boris Mikhailov and Diane Arbus), and can’t pretend much knowledge subsequently, but I was struck by the strength that many of the individuals whose images are captured here derive from peer groups.

Whether it be the retro, rockabilly, multi-racial Parisian gangs photographed by Philippe Chancel, the very cool Teds of Chris Steele-Perkins, Danny Lyon’s Easy Rider biker mates, Bruce Davidson’s early 1950s New York ruffians and, most strikingly for me, Igor Palmin’s Russian hippies, there is an obvious attraction in these rebels. Choose your tribe. I never quite got over being too young for the Summer of Love.

The exhibition kicks off with the legendary Diane Arbus’s portraits of circus performers, nudists, transgender people and others from the 1960s and 1970s. Hard to believe she started as a fashion photographer alongside husband Alan. These portraits border on the intrusive and sensational but there is no doubting their influence on later generations. Take a look upstairs at Katy Grannan’s intimidating portraits of those who aren’t now part of the American Dream, or Alec Soth’s documentation of US survivalists.

The best of the rooms downstairs shows the work of Daido Moriyama and follower Seiji Kurata. The former’s blurred nighttime photos of the murkier side of Tokyo, and the latter’s more polished studies of a similar milieu, are more disquieting than some of the other groups on show. Here is real confrontation. As there is in the Tulsa photos of Larry Clark; he is one of the teens shooting up here.

The most striking documents though downstairs are to be found in the vitrine full of holiday snaps taken at Casa Susanna in the early 1960s. Casa Susanna was a weekend retreat for transgender women and cross-dressing men run by Susanna Valenti and her wife Marie in New York State. Remember this was a time when being publicly transgender was still a criminal offence. The photos were taken by Andrea Susan, one of the guests, which explains their relative quality. They were eventually discovered in a flea market and published a few years ago and inspired the play Casa Valentina at Southwark Playhouse in 2015. Everyone seems to be having a good time. It’s pretty uplifting.

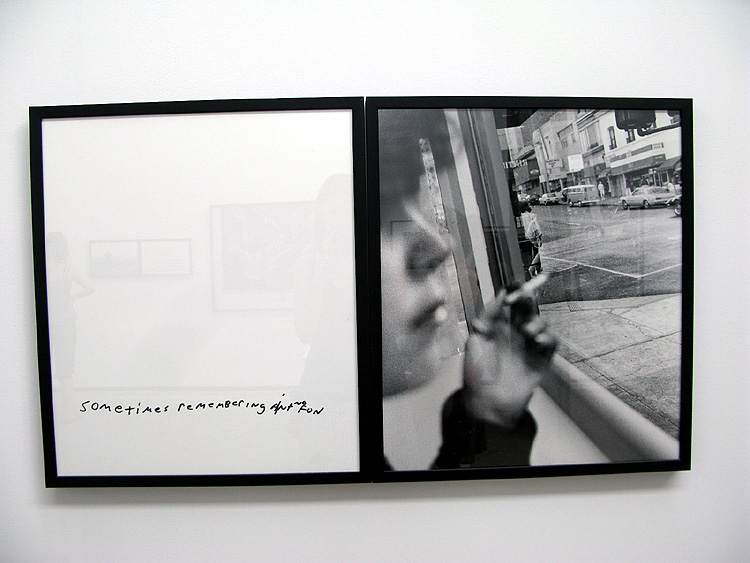

The photographers showcased upstairs are more focussed on individual or small group portraits. Most striking perhaps are Jim Goldberg’s stories of street teenagers, led by Dave and Echo, from California first published in 1995 entitled Raised by Wolves. His observational technique, accompanied by text, video and other material, is pretty harrowing, and it does, like other material in the exhibition, get you to thinking about the relationship between photographer and subject and your own relationship, as you trot around the gallery in the company of an audience of observers who are firmly within the mainstream of society (even if some may think they are not), with the subjects here, who have been forced, or chosen, or some combination thereof, to be “different”. Queasy voyeurism comes with the price of the ticket here.

The intervention of the photographer is most acute in the small room devoted to Boris Mikhailov’s photographs of a staged wedding of a homeless, alcoholic couple in contemporary Russia. It is provocative but it gets its point across. I found these hardest to look at. Paz Errazuriz’s pictures of transgender women from Chile are doubly arresting, precisely because that is what would have happened to her is she had been caught taking such photographs in Pinochet’s Chile.

You will also be intrigued by the stories behind Pieter Hugo’s portraits of Nigerian men and their captive animals, hyaenas and baboons, that live on the fringes, and alarm, South African society. Mind you some of them are gang members, drug dealers and debt collectors so the fear may be justified. They are certainly imposing and, I think, the photographs which I found most aesthetically pleasing if that makes sense. Pathologist turned conceptual artist,Teresa Margolles’s pictures of transgender prostitutes set amidst the ruins of their nightclub workplaces in Mexico, pulled down by the authorities, in an attempt to move them on, have a similar artistic sensibility.

I realise as I have written this, and learnt more about the photographers involved, that I probably need didn’t try hard enough and need to revisit and relook. That’s what can happen if you have time and an open mind. Time, and open minds, is what changes attitudes, beliefs and behaviours.