Isabelle Faust (violin), Kristian Bezuidenhout (harpsichord)

LSO St Luke’s Old St

JS Bach

- Sonata no 3 for violin and harpsichord in E major BWV 1016

- Partita no 2 for solo violin in D minor BWV 1004

- Sonata no 1 for violin and harpsichord in B minor BWV 1014

- Toccata for harpsichord in D minor BWV 913

- Sonata no 6 for violin and harpsichord in G major BWV 1019

The second instalment in Isabelle Faust and Kristian Bezuidenhout’s rendition of the six JSB violin sonatas BMV 1014-1019 following on from the Wigmore Hall in April. (Isabelle Faust and Kristian Bezuidenhout at Wigmore Hall review ****). Once again they allowed themselves a solo each, but this time some more JSB, in keeping with the Bach Weekend theme, which also celebrated the 75th birthday of the venerable Sir John Eliot Gardiner.

This time I was joined by Bach groupie MSBD. Early start. 11am on a Saturday. I wish every day started this way though.

At times JSB is truly sublime. More so that any other composer. You might find it in the cantatas, others in the masses or passions, or maybe the keyboard, instrumental ensemble works or the cello suites. Not for one moment could I disagree with you but, for me, the apotheosis of JSB’s genius lies in the violin sonatas and partitas, solo and accompanied. Great art induces a state of rapture. Not the nonsense exclusive coach trip into the sky that some befuddled Christians cling on to, but the state of grace, individual or collective, that you can feel inside your whole being when dancing in a club, or breathless and motionless in the theatre, or when your ear sends pure sound to your brain at a concert or when you get lost in a painting. It doesn’t happen much, just as well as that might overwhelm, but it is part of what makes life worth living. I appreciate that this might be a terribly old-fashioned way to think about art but I dare you to tell me I am wrong.

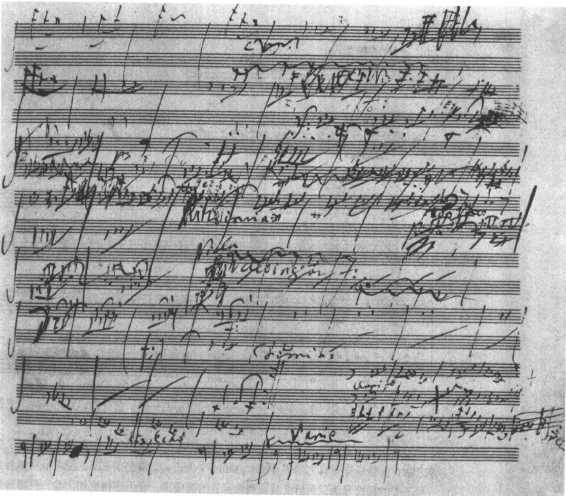

Anyway it happened here. In the final movement of the Partita. The immense Ciaconna. Amongst Bach’s finest creations as the programme says. They’re not wrong. It gets me most times but here, OMG, Isabelle Faust, her violin, St Luke’s, my ears, my brain, the audience, and of course, old JSB all came together as one. This old buffer did his best to hold back a tear. It is so simple, just a basic four bar pattern, (apparently “the harmonisation of a descending tetrachord” – thanks again programme notes). But JSB is able to do so much with it including a huge mood shift about two thirds of the way in. This is when you might just believe that JSB reconciles himself to the early death of first wife Maria – he was to meet Anna just a year later.

The accompanied sonatas came close to their solo cousins. I have banged on before about just how expressive Isabelle Faust is when it comes Baroque violin. She’s pretty handy too when it comes to the rest of the canon. Listen to her recordings of the Beethoven, Bartok and Berg concertos if you don’t believe me. She can even persuade me with her historically-informed interpretations of that Mozart chap. But Bach is where she enters a different realm. She applies an astringent, almost abstract, rigour which just blows me away. And KB, who has a gentler conversation with his harpsichord, is the perfect accompanist. IF doesn’t muck it up with unnecessary and unwarranted vibrato, and both the left and right hand lines for KB are clear and not jangly. This leaves plenty of room for the sonatas to breathe and, in the superb space that is St Luke’s, with the sun streaming in from outside ….. well you can see where I’m coming from.

JSB continued to revisit and buff up the six sonatas throughout his life. Maybe that’s why the old boy perfected his art here. In the early decades of the C18 the trio texture was considered the compositional ideal for chamber music, creating a perfect synthesis of linear counterpoint, full-sounding harmony and cantabile melody, (thanks once more programme notes). Put this trio principle into the hands of the man who got closer to the ideal of perfect harmony than anyone else in the history of Western music, with the melodies driven by the finest of instruments the violin, then obvs it was going to work. JSB created trio works for flute, viola da gamba (which I like) and organ but they don’t come close.

Listen to No 1, BMW 1014. It kicks off with a 5 part texture with double stopping and a 3 part effect on the harpsichord. The two quick movements, (the first 5 sonatas stick to the old skool sonate di chiesa four movement set up with No 6 breaking free into 5 movements), have each of the three lines chipping in together, the perfect realisation of the trio principle with the third movement switching to violin and harpsichord right hand weaving around a left hand bass. No 3 BMW 1016 kicks off with a slow movement where both players can show off their skills, followed by a bouncy fugue, a powerful lament in C sharp minor before rounding off with an extraordinary gallop where the violinist can really show off. No 6 BMW 1019, is very different, with a central solo harpsichord movement flanked by two jolly giant Allegro opener/closers (real faves) and two slow, simple (-ish) shuffles in a kind of canonic form.

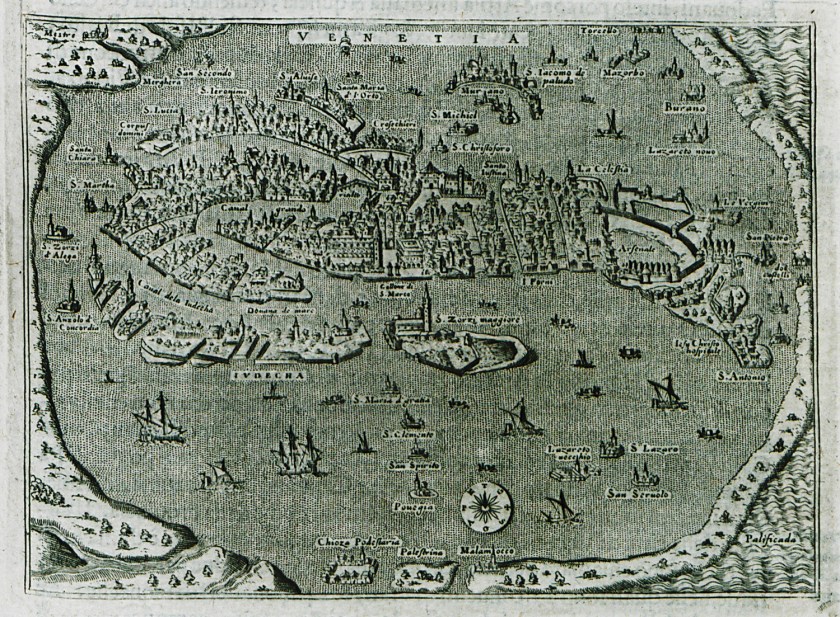

Other than the aforementioned divine Ciaconna the Partita No 2 consists of 4 dance movements, an Allemanda, a Corrente, a Sarabanda (which foreshadows the Ciaconna) and a Giga. We have Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Kothen’s Calvinism to thank for JSB’s discovery of all things boogie as he wasn’t confined to elaborate Church music in the Prince’s employment. (We also have the genius Antonio Vivaldi to thank for the twin graces of rhythm and repetition that underpin JSB’s unique ear for inventive sonority).

Other than the Sarabanda thsee dance movements are all monophonic in structure so easy to understand and have a dominant rhythm from which the violin goes off on ever more exciting harmonic excursions. It was a massive hit when first published and performed and remains so to this day. It really is very easy to see (and hear) why. You do not need to have any interest or understanding of classical music to get this. You just need ears and a pulse. So whatever your musical bag, I implore you to listen to it. IT WILL MAKE YOUR LIFE BETTER. I promise.

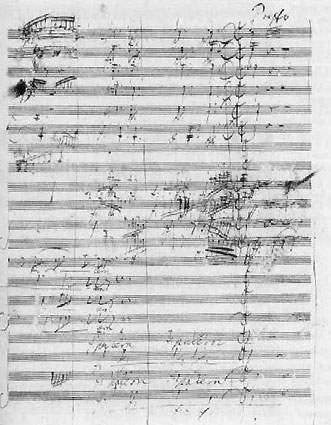

KB had a little less time to shine though not by much as he picked the most extensive of the six toccatas, BMW 910-916. The D minor 913 was composed when JSB was just 20 as he went AWOL from his job and walked the 450kms to Lubeck to hear Dieterich Buxtehude play. So next time you complain about how tricky it is to get to the Barbican think on JSB’s devotion. It opens with a typical Baroque improvisation, (typical for others that is), followed by a couple of JSB trademark fugues linked by a bridge which shifts tempo and ending with a tierce de Picardie, a major chord at the end of a minor key piece, which JSB was partial too. After the Partita and the first two sonatas this harpsichord piece shifted the mood before the final, jolliest, No 6 sonata. Smart programming and smart playing, (I only know these toccatas from the never surpassed Glen Gould on piano).

So there you have it. This will definitely be a top 10 2018 concert for me and I am pretty sure for MSBD, though I have lined up a few more for his delectation. And I wonder if, by the end of my musical education, I end up realising that no-one topped Bach. It is beginning to feel that way.