Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, Kaspars Putnins (conductor)

Milton Court Concert Hall, 30th January 2018

Arvo Part

- Solfeggio

- Summa

- Magnificat

- Zwei Beter

- The Woman With the Alabaster Box

- Nunc dimittis

- Dopo la vittoria

Cyrillus Kreek

- Onnis on inimene (Blessed is the Man)

- Psalm 104

Jonathan Harvey

- Plainsongs for Peace and Light

- The Angels

Veljo Tormis

- Kutse jaanitulele from Jaanilaulud (St John’s Day Songs for Midsummer Eve)

- Raua needmine (Curse Upon Iron)

Now I gather that the Estonian people like a sing-song. Choirs are a big deal there and choral singing and national identity are tightly bound together. They even had a Singing Revolution between 1987 and 1991 as they sought independence from the Soviet Union. So this evening was an event and was graced with the presence of no less than Estonia’s Prime Minister Juri Ratas.

Now I am not going to pretend this was the main draw for me. Profound apologies Your Excellency, but what intrigued me was the opportunity to here some of the choral works of the mighty Arvo Part sung by his country men and women. Albeit mostly in Latin, with a German, English and Italian text thrown in for good measure. Now I genuinely believe that the magic of Part’s “holy minimalist” tintinnabuli can work on anyone. I believe I am right in saying he is the most performed living “classical” composer. That doesn’t mean people are whistling Speigel am Speigel on every street corner though. This is still a minority pastime, but I do think there is something in his music, (and the spaces between the notes), which can burrow into the soul of all who come across it. Not that they have souls. That is obviously mumbo-jumbo. Old Arvo might sign up to Orthodox Christianity but not me. But it does something. Even if it is just to clear the head and leave you suspended in the sound for the duration of the piece.

So it was a pleasure to rope in MSBD to the Part party. Now, in retrospect, it might have been better to break him in gently with the usual programmatic device of interspersing Part’s choral works with other contemporary composers who relish the challenge of a choir as well as selected Renaissance masters. Even I have to admit that seven of Part’s choral works back to back can induce a slowing of the heart rate that is difficult to distinguish from slumber.

The opener Solfeggio is particularly interesting. It was originally written in 1964, though I think refined in 1993, which means it actually came before Part announced himself to the world with the bang. crash, wallop of Credo for chorus, orchestra and piano in 1968. This remember was when Part was a paid-up serialist, although Credo for my money is still a cracking piece of music. Solfeggio asks the choir to trot out an ascending C major row in strict serial fashion, singing, would you believe, “do re mi … “, but you’d be hard pressed to tell it apart from the “classic” Part style which emerged in 1977 after the several year hiatus and his personal enlightenment.

Summa is a setting of the Credo from the Latin Mass, though its title conceals its origin, composed in the pivotal year of 1977. It was, along with Part’s settings of the Magnificat (1989) and Nunc dimitis (2001) for the Anglican evensong, the most entrancing of the evening’s performances. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir has a bewitching and very exact delivery with clear definition across the parts. This means the intriguing shifts that Part employs here, and the shimmering climaxes, especially in the Nunc, seemed more suited to their style. In contrast the more direct The Woman with the Alabaster Box from 1997, sung in English and which sees adjacent thirds appear under long sustained notes, was less thrilling to me than the Latin texts, which are all based on Part’s “classic” stepwise triads.

Zwei Beter, based on the parable of the Pharisee and the Publican I gather, is a more complex beast, (it’s all relative mind you), with denser harmonies and sung in German. Now one way or another I have recordings of most of Part’s works, (I think some remain unrecorded), but I didn’t know this piece at all. In contrast I am familiar with Dopo la vittoria from 1996 which is also somewhat more “complex” than the Latin texts. Sung in Italian this “piccolo cantata” tells the story of the baptism of Augustine by St Ambrose, (who apparently broke into song whilst doing the necessary), the patron saint of Milan for which city it was written. There is a discernible story with defined sections, including a brisk opening and ending, and some pronounced homophony at crucial, uplifting points. Who said Part all sounds the same.

After the interval we were treated to a pair of psalm settings by Cyrillus Kreek, an Estonian composer from the generation prior to Part, and a man who devoted his life to setting the country’s rich legacy of folk songs into choral arrangements. These songs stem from the wave of Estonian nationalism that stirred in the second half of the C19. These two pieces were very easy on the ear and sung with real conviction by the choir. A pair of works by British composer Jonathan Harvey followed, from the end of his career. Harvey regularly turned to choirs alongside his electronic and chamber pieces. The Angels was set by the Bishop of Winchester to which Harvey adds a hummed accompaniment. Plainsongs is more substantial polyphony with some beautiful, gently dissonant passages across its sixteen parts.

Finally the EPCC treated the audience to two works from Veljo Tormis, who passed away last year, after actually retiring in 2000. Slightly older than Part, but possibly even more renowned in his homeland, with a huge body of choral work to his name. Most of the settings stem from Estonian folk songs and I gather it is fair to say he has inspired multiple generations with his music. He was born during Estonia’s short lived inter-war period of independence, lived through the German and Soviet annexations and the Socialist Republic, and through to independence again. He mixed with all the big names during his musical education in Russia and was “honoured” with his own KGB files.

The first piece belongs to a cycle which describes the important Midsummer celebrations. It starts simply enough but builds into something more sophisticated. The Germanic influence is clear. But this was just a taster for the extraordinary Curse of Iron which followed. Apparently this gets a fair few airings outside Estonia and it isn’t difficult to see why. To the rhythm of a simple drum beat throughout, and with solo bass and tenor parts, Mr Tormis sets a story based on a Finnish epic, but sung in Estonian. It is, like it says, a curse on iron, as you do, and it is very dramatic. A ritual with repeated ostinatos, I have never heard anything like it. Neither had MSBD. Imagine a kind of shamanistic chant which ends up with sopranos warning against nuclear proliferation. Can’t. Well go and hear it then. It’s on I-Player since the concert was recorded for Radio 3.

Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir concert recording

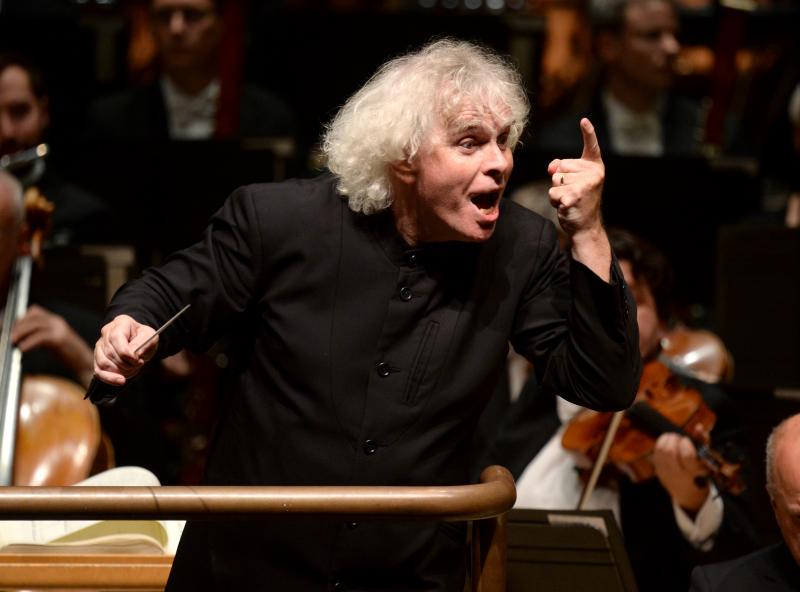

A riveting way to end the concert and unsurprisingly the EPCC, and especially their Latvian conductor Kaspars Putnins, were having a ball during it. If I were part of the Estonian guest party I would have found it pretty difficult not to get up and join in. Pride in their country but pride in Europe too methinks. Great stuff.