Porgy and Bess

English National Opera, 31st October 2018

It has been a long time coming. This co-production, together with the Met and the Dutch National Opera, is the first time it has appeared on the Coliseum stage. The re-written version, with book by Suzanne Lori-Parks, (which attracted the ire of Stephen Sondheim no less), popped up at the Open Air Theatre a few years ago and I gather that Welsh National Opera staged the Cape Town Opera production transcribed to South Africa in 2009. Prior to that I believe you have to go back to Trevor Nunn’s various tilts, at Glyndebourne in 1986, the Royal Opera House in 1992 and the less than successful musical theatre version, with speech replacing recitative, from 2006 at the Savoy. (Which, I have surmised, was what my special guests for this evening BUD and KCK, must have seen).

You’d think with all those tunes it would be a far more regular feature. On the other hand, one look at the set, and the massed cast at the opening of this production, perhaps reminds you why it is such an infrequent visitor. This must have cost a few bob. And assembling this many fine black singers from around the world, for this amount of time, will have required a patient, and skilled, logistical hand. The ENO has come under the cosh in the last few years, often unfairly in my view, so it is terrific to see that this has been a resounding critical and commercial success with standing room only across the run.

That is not so say it is perfect, at least from where the Tourist was sitting. (Nothing wrong with the view mind, though the old back was playing up a bit). The First Act does go on a bit: a fair few punters took the steamboat whistle as their cue to head to the bar. The chopping and changing of the time signatures in the jazzier parts of the score gets a bit wearing and I wouldn’t have minded if debutante conductor John Wilson has taken some passages at a greater lick. Not to say that he dawdled, just that I am all for brevity and clarity when it comes to orchestral music.

The plot and characterisation is very much of its time, Charleston in South Carolina in the 1920s. Not woke for sure. Even in the 1930s casts and creatives wrestled with the stereotypes that the opera presents. By the 1960s the opera had been pretty much consigned to the dustbin: no-one would perform it. It wasn’t just the characterisation, plot and language that vexed but also the appropriation of musical styles. In the last few decades performers have reclaimed the piece however, notably in South Africa. Ira Gershwin refused permission for the opera to be performed with white casts under apartheid as he and George had from the outset. Their stipulation for black only casts hasn’t always been maintained however, most notably by the Hungarian State Opera in their last season with a predominantly white cast, which looked, on the face of it, like a political provocation.

Having said all that I can absolutely see why the creative team, led by James Robinson AD of the Opera Theatre of St Louis, on his ENO debut, have played this absolutely straight, (and I suspect they always had one eye on the reception from the punters at the Met). Putting the condescension to one side, the characters in Porgy and Bess, even if there are probably too many, are more emotionally rounded than in most opera, and the drama, with its mythic underpinning, more engaging. This in large part reflects the work of Dorothy and DuBose Heyward from whose play and book the story is taken. That doesn’t mean it is without flaw however. Porgy’s seeming accommodation of his poverty and disability, Bess’s total lack of agency and final descent: these require a great deal more exploration than the few lines that opera can offer, especially one where so many other voices are heard. And Gershwin’s music as it slips from folk to jazz to blues to gospel to spiritual to, very obviously in the melodies of some big songs, his own Jewish heritage, doesn’t always match up to the psychology of the character. Say what you like about Mozart and Da Ponte’s plots, when words fall short and music needed to take over, Wolfgang was your man.

George Gershwin’s ability to mix popular, musical theatre with high art classical composition is there from the very beginning of the piece. The jazzy theme for full orchestra that emerges from the frenetic opening, with the entire cast on stage, drops down to a simple piano roll. Then Clara emerges and launches into you know what. If there has ever been a tune that more defines time and place in musical theatre, the bluesy Summertime is it. It’s hot, we are on Catfish Row and, for a lullaby about protecting the child, there is something infinitely sad about it. Which of course there is when it subsequently re-appears later on before the murder of Robbins by Crown and after the fatal storm.

Up to now George and lyricist brother Ira had delivered Broadway musical but George was determined to filter this through European classical modernism to create a unique American opera style, just as Bernstein would in the following decades. They must have got something right in this their operatic debut. The programme mentions an estimate of 25,000 version of Summertime. Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald and The Fun Boy Three in my library. From there on, for all the twist and turns of the music when it stands alone or supports the recitative (and kind of arioso), for all of the musical call-forwards, call-backs and motifs it is the songs and arias that the audience came to hear. Gone, Gone Gone, spirituals My Man’s Gone Now and It Take A Long Pull To Get There, It Ain’t Necessarily So, love duet Bess You Is My Woman Now,, Oh Doctor Jesus, Oh Lawd I’m On My Way., even banjo song I Got Plenty of Nuttin’. Hard not to be carried away by that lot.

I have said before that I am not up to the task of commenting on the technical skill of the performers and, for me, acting in opera is as important as singing. If I had to pick out individuals then I would plump for Eric Greene’s rich, powerful baritone voice, which builds through the evening, and the poignancy he brings to Porgy. Nadine Benjamin’s sweet, sensitive Clara and Frederick Ballentine’s oily Sportin’ Life also stood out and I was taken with, at our performance, Gweneth-Ann Rand’s noble Serena and Tichina Vaughn’s gritty (acting not voice!) Maria. Soprano Nicole Cabell’s Bess was a little too reticent at times and Nmon Ford’s Crown, complete with rippling torso, a little too brisk, but what do I know. It is though when the chorus and orchestra come together in the big set-pieces, the fights, the murder, the funeral, the prayer-meetings, when the opera really takes off, and this chorus drawn from as far apart as the US, South Africa and New Zealand, was as good as I have heard anywhere. This was when I got the “opera buzz”. I am looking forward to the War Requiem that will follow at the ENO from this chorus.

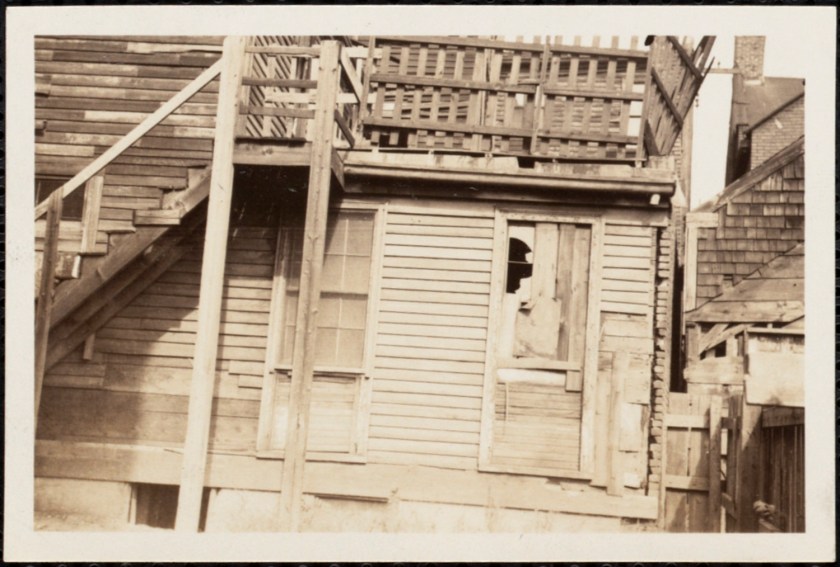

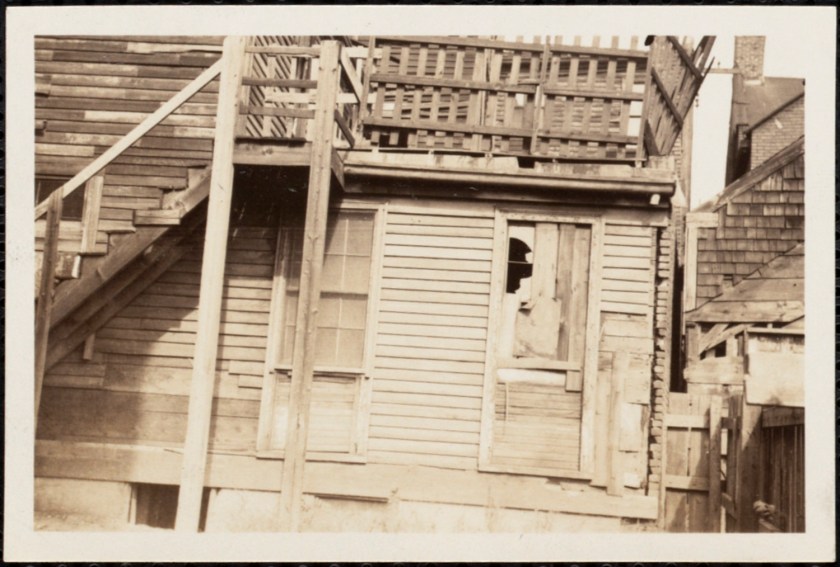

For all the story-telling, playing, singing and dancing (courtesy of Dianne McIntyre) though, it was the look of the production that was perhaps the best thing about it. The set from legendary American designer Michael Yeargan, gives us the the bare bones of the Catfish Row tenements. The flesh then comes from another legend, lighting designer Donald Holder and the video design of our own Luke Halls, who is about the best in the business. No innovative representation or symbolism here. Sun, rain, water, daybreak, twilight, moonlight, quick time, slow time, public space, private space. All were vividly imagined. Catherine Zuber’s costumes are equally effective. Wheeling out the best of Broadway and pooling the budgets of the three producing houses has paid dividends handsomely. Even the SO to whom plot is everything was bowled over by the look as were keen companions BUD and KCK. We definitely got our money’s worth.

I see that I have a recording of Porgy and Bess, the LPO under Simon Rattle. I don’t listen to it though. I do listen to Miles Davis’ instrumental versions though, which are all over the shop. Not sure what that means. Essence of trumpet maybe.