The Turn of the Screw

Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre, ENO, 29th June 2018

Benjamin Britten. The Turn of the Screw. Members of the ENO Orchestra conducted by up and coming talent Toby Purser. Timothy Sheader directing. A Soutra Gilmour set. At the Open Air Theatre. On a beautiful late June evening. In the company of the SO, (who loves her Henry James and surprised herself by enjoying Deborah Warner’s staging of Death in Venice in 2013 at the ENO), BUD and KCK. Of course I was going to love this.

One of the aims here was to extend young BUD’s operatic education beyond Mozart. As he remarked here, not a lot of tunes.. Not sure I agree but there is no doubt in my mind that Britten’s music became darker through time, cleverer, from an already very high base, more progressive and less conservative, whilst never embracing the fearsome avant-garde, and richer, even as textures got sparser. The tonality is tempered with lots of (lovely) dissonance.

I think TTOTS occupies a key place in the development of all of Britten’s art. It was composed in 1954, just after Gloriana, and three years after Billy Budd. In the same year Britten composed his Canticle No III, Still Falls the Rain for tenor piano and, Britten’s favourite, horn. This is recognisably BB, like a trip-hop version of the Serenade Op 31, but this, and the Winter Words song cycle from 1953, seem more melancholic than the warmer equivalents before the war. Britten himself said that his music was forever changed by the WWII, as was true for pretty much all Western art, notably by a visit to Belsen, but I don’t think this really becomes apparent until the mid 1950’s.

Anyway TTOTS is definitely an example of the “less is more” BB where surface effect is toned down a little, (though not jettisoned entirely, there are plenty of ravishing musical ideas here), in the service of greater structural and emotional depth. And structurally this is a score of genius as a tightly wound serial “screw” theme and set of 15 variations built on a different semitone, opens each scene, ratcheting up the tension. So, you see BUD, there is a “tune”, you just hear it in a different way.

Which I think is why it is such an effective piece of musical theatre, an opinion with which BUD heartily conferred. TTOTS is apparently BB’s most performed opera. And probably the most performed opera in English. And, after your man Puccini, probably the most performed opera from the C20. Certainly the most performed of those operas written since the war. In part this reflects its chamber structure. With just 13 instrumentalists and a cast of 7, this is no big budget affair. As was intended. However I also think it reflects near perfect synthesis of story, libretto and music. All three offer a sufficient challenge to an audience but in no way is this intimidating. It always takes a bit of time to get swept up into a Britten opera, but swept up you will be, even if it isn’t the massive, warming, rush of Mozart.

In retrospect it was pretty much a nailed on certainty that BB and Myfanwy Piper would alight on Henry James’s novella. BB, and his various librettists, always started with an artistic inspiration. Usually the story revolved around an “outsider” estranged from the society around him. There’s usually some sort of spiritual dimension. And, nailed on, there will be some sort of uneasy “corruption of the innocent” theme. TTOTS has all of the requisite elements in spades. Better than this though is the ambiguity embedded in the story. What really happened at Bly? What was, or is, the nature of the relationship between Miles and Flora, Miss Jessel and Peter Quint? Who, and what, can we see? Who, and what, do the characters really see? After all only the Governess apparently sees the ghosts in HJ’s original. Is this all in the Governess’s mind then? How are we being manipulated? Strange to think then that the story came to HJ via none other than the future Archbishop of Canterbury in 1895.

Myfanwy Piper’s text reads like a poetic, musical impression of Henry James’s book but it picks its highpoint carefully. On to this BB’s score is perfectly stitched. In the book, told through the first person narrative of the Governess, it is up to you to imagine what happens. In my estimation, and those way smarter than me, its psychological depth and disturbing themes, take it beyond your bog standard gothic ghost story. In the innumerable film and TV versions, the ghosts can be made to seem like the extensions of everyday reality that HJ intended (I think), thanks to the trickery of the camera, but you all get one view, one take on the story. In a version for stage as here, (or notably The Innocents or the 2013 Almeida take), Quint and the Governess are undeniably corporeal, (any design team which could escape that mortal fact would get my money, no question), especially if they are going to sing, and the children are going to sing to them, and scenes unfold where the Governess is not present. So the mystery and ambivalence has to come from the music. And I cannot imagine anyone better than Britten at facilitating this.

But BB and MP take things a lot further. Take Miles’s famous Malo song that is repeated by the Governess at the end. Haunting for sure with viola, horn and harp. Malo in Latin could either mean “bad”, “to prefer” or an apple, symbol of innocence. “I would rather be… in an apple tree … than a naughty boy … in adversity”. The Latin words recited in the lesson prior to this contain all sorts of sexual references. Miles wanting “his own kind” and reflecting on his “queer life”. Mrs Gross’s line about Quint being “free with everyone” allowed to linger in the Regent’s Park air. Blimey. This is how the opera adds a new dimension contrasting the order and convention that the Governess clings to with the liberty that Quint offers whilst not seeking to mask the implication of abuse.

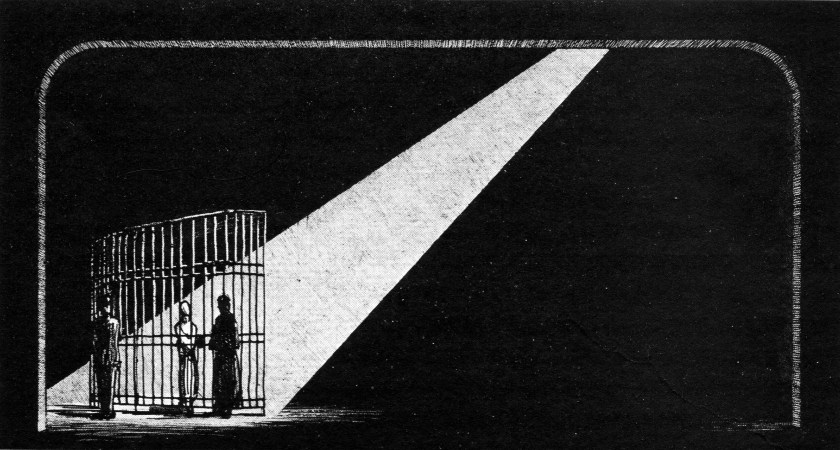

So, as you can see, I am a fan of this opera. What about the production then. Sandra Gilmour has imagined the remote country house of Bly as a large, dilapidated conservatory fronted by overgrown grass and a jetty leading to the “lake” and into the audience. It was amazing. Timothy Sheader, after a decade at Regents Park, now knows exactly how to use the unique space to best effect. TTOFTS was pushed out to an 8pm start to ensure sunset and early twilight matched the change in dramatic mood in the story and provided a perfect backdrop for lighting designer Jon Clark to show off his skills. Quint and Jessel make entrances from within the audience. Even the parakeets flew over on cue, “the birds fly home to these great trees”, at our performance. The debacle of last years Tale of Two Cities is entirely forgiven. The pacing was sublime and the musicianship top notch, especially, the viola of Rebecca Chambers, the clarinet of Barnaby Robson, the horn of John Thurgood and the harp of Alison Martin. Putting the orchestra inside the conservatory, behind a panel of ancient glass, thus lending them a ghostly quality, was a genius touch.

On this evening ENO Harewood Artists Elgan Llyr Thomas played Peter Quint with William Morgan taking the Prologue. Mr Thomas’s tenor voice is clear and direct, through the melismas especially, and fitted the space. I was a little less sure about his wig and beard combo. Anita Watson was a suitably unhinged Governess, for me she was convinced this was really happening, and Elin Pritchard a very disturbing, steampunky Miss Jessel. Janis Kelly, who has in her time played Flora. Miss Jessel and the Governess, now played a protective Mrs Gross. Daniel Alexander Sidhorn’s precociousness made for an arresting Miles though I have to say Elen Wilmer’s Flora was, for me, the more impressive voice. As an actor though Master Sidhorn is the real deal. Simultaneously vulnerable and malign.

Indeed Elen matched the elder Elin in look and movement creating a “bond” between Flora and Miss Jessel as disturbing in its way as that between Miles and Quint, an unexpected bonus. Mind you when Miles dons his purple shirt to match Quint’s and when he takes over from Quint on the piano, (young Sidhorn is either a mighty fine pianist or an even better “piano mimer”), the audience was bolt upright in their collective seats. And, on top of all of this, Mr Sheader really messed with our heads with a provocatively erotic scene as the Governess, “lost in my labyrinth”, asleep, is joined silently by Quint and Miss Jessel, or more specifically her hair, with Flora’s symbolic dolly and with Miles’s symbolic jack-in-the-box. Oh and did I say Miss Jessel is pregnant here.

One final thing. It’s outside. Which means a little technology is required to keep the volume stable as it were for both ensemble and singers. Which meant every word, with a couple of exceptions when Anita Watson’s soprano heads off to the higher registers, was crystal clear. Didn’t stop me consulting the libretto on occasion but what it did mean is that, for maybe the first time ever, I could savour every word of the libretto, to set alongside this stunning score and this tremendous production. This is what theatre, and opera, should all be about.