The Intelligence Park

Linbury Theatre Royal Opera House, 2nd October 2019

I have no-one else to blame for this. Having now heard a smattering of his larger scale works thanks in large part to Thomas Ades’s advocacy in his Beethoven cycle with the Britten Sinfonia, having invested in a CD of his chamber works and having thoroughly enjoyed the semi-staged version of his opera The Importance of Being Earnest at the Barbican a few yeas ago, I would certainly count myself a fan of Gerald Barry’s bracing, spikily rhythmic composition.

There were plenty of knowledgeable commentators however, including the composer himself, who warned that this, his first opera from 1990, is not the most transparent of entertainments. Though it was lauded on its first showing at the Almeida, largely for the music I gather, its plot is convoluted, the libretto from Barry’s Irish countryman, and Joycean scholar, Vincent Deane is florid, bordering on the impenetrable, and the aural intensity unyielding. Barry delights in music that bears no necessary connection with character, action or phrasing. 90 minutes, even with interval, is probably as much as even the most sympathetic of listeners can take.

And yet, out of this assault on the senses, comes something which is, well if not enjoyable, is certainly remarkable. The story, whilst admittedly needing more than a nudge from the programme synopsis, is no dafter than most opera buffa, complete with a knowing meta quality which I suspect would have appealed to C18 audiences. Something that Haydn would have attempted. Though also with an underpinning of Handelian serioso that the setting of this opera, and its successor, The Triumph of Beauty and Deceit, (how’s that for a late C18 opera catch all title), implies. Even so GB has said “as to what The Intelligence Park is about, I have no fixed idea” though there may have been with tip of tongue in cheek.

It is Dublin. 1753. Composer Robert Paradies (bass-baritone Michel De Souza) is struggling to complete his opera on the romantic tryst between warrior Wattle and enchantress Daub. Best mate D’Esperaudieu (Adrian Dwyer) pitches up to remind him of his impending marriage to Jerusha Cramer (Rhian Lois) which is required if he is to inherit Daddy’s riches. The boys pitch up to a party at Sir Joshua Cramer’s (Stephen Richardson) townhouse. Jerusha starts singing but is interrupted by her teacher, visiting castrato Serafina (Patrick Terry) who is in attendance with his bessie Faranesi (soprano Stephanie Marshall). Paradies falls for Serafina and falls out with D’Esperaudieu.

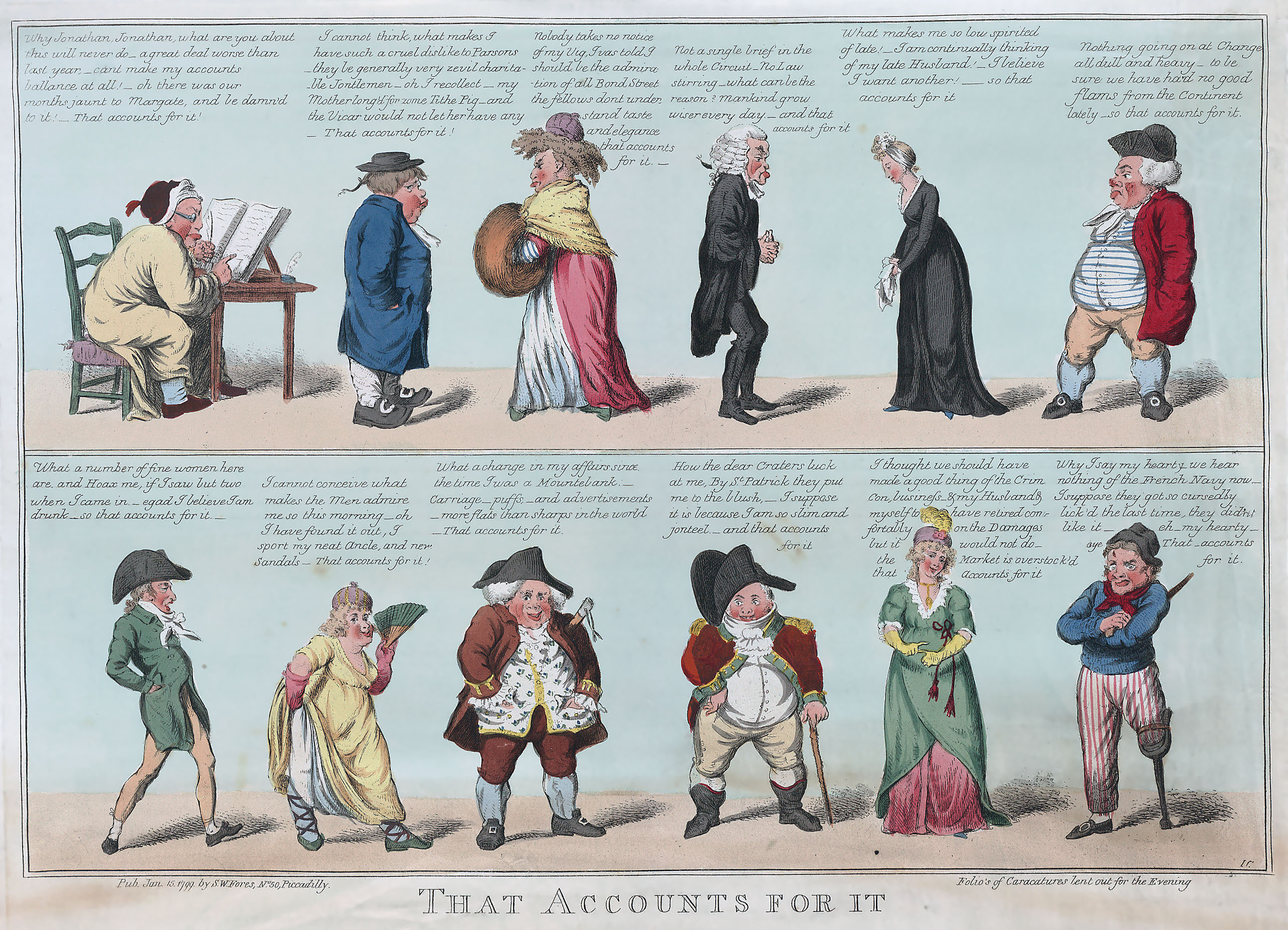

Then it gets properly weird as the Wattle and Daub characters, complete with puppet heads (!), pitch into the real proceedings and we find out Jerusha also has the hots for Serafina. Fantasies, arguments, elopements, a series of comic (sort of) vignettes, revenge, a banquet and death all pile up as art and life collide. Though frankly, even as I had secured a better viewing perch, (a few punters gave up at the interval), it all got a bit confusing post interval. No matter. The tropes of classical opera, (and Georgian comedy), were all on show, no doubt there were allusions and quotations that went right over my head, which Nigel Lowery’s ironic, cartoonish Baroque vision, as set and costume designer, director and lighting designer, sought to play up. Think Hogarth on acid.

I also gave up on the subtitles. Not because I could make out what the cast were singing. That was impossible. Not because of any failing on their part. To a man and woman they were tremendous given the singing, acting and, critically, concentrations demands made upon them by GB’s score. Take Stephen Richardson’s bass part which keeps flipping from its lowest register into falsetto, sometimes mid line. (Hats off to repetiteur Ashley Beauchamp who certainly earned his fee). No the fact is, after a while trying to take in Mr Deane’s densely connotative text, it just became too much to take in alongside the music and the visuals. In my experience contemporary opera can veer towards the sombre and static. Not here. This is intensely theatrical.

So you are probably thinking, based on the above, that this was all a bit shit and only really shows the Tourist up as the pseud he is. Well no actually. Just because I can’t cover all the bases in terms of plot, character, message, text doesn’t make this a bad opera. The story is deliberately confusing and the music deliberately unsettling and that is what makes it interesting and intriguing. Being challenged by art is all part of the deal and opera is pretty binary when it comes to comfort or challenge. If you want the former then Handel or Mozart will probably float your boat, and I admit, often mine too. But sometimes exposing yourself, as here, to their evil twin can be bracing. Remember the first time you heard the Sex Pistols? Same thing.

Barry has described The Intelligence Park as being set an an “unsettling diagonal”, a fair description. TIOBE, and Alice’s Adventures Underground which will appear next year on the main ROH stage courtesy of WNO, in part because we know what we are looking at (even through the looking glass) and because they are funnier, (deadpan humour is a big part of GB’s shtick), are easier fare to digest but GB’s musical language is still a long way from most of his historical, and contemporary, peers. Opera, however daft or reactionary the plot, insists that the participants really mean what they are singing. Emotions run high, feelings are big and bold. GB undercuts, though doesn’t subvert, all of that with his music normally going out of its way to upset the expected code. Shifting time signatures. Voices careering across the register. High notes when there should be low and low when they should be high. Stopping mid line. Repetition but of the wrong word at the wrong time. Exaggeration at points of banality or curious indifference at points where emotions should be highest. Unusual accentuation as GB terms it. The plot may be linear. The music is not. There is steady pulse and rhythm often at a fairly brisk lick, with one beautiful lyrical passage excepted, and there is plenty of noise when required. But none of the “divine” interplay of music, libretto and emotion that Mozart and da Ponte conjured up. These obsessive characters are not in control of the music, they are being attacked by it.

This relentless energy and manic aggression is tiring and sometimes frustrating but it is undeniably thrilling and there are so many brilliant, unpredictable musical ideas that it is better to go with it than set your will against it. After all, whilst there may be dissonance, there is harmony, lots of it, just not always pretty. Needless to say the London Sinfonietta took the score in their stride, they thrive on stuff far more challenging than this, but it takes a conductor of guts to take this on. Jessica Cottis is rapidly becoming the opera conductor of choice for challenging new and recent opera and here she wisely promoted vigour and animation over precision.

After the six performances, (same number as for next year’s sold out Fidelio – go figure), at the Linbury this Music Theatre Wales/Royal Opera co-production went on to Cardiff, Manchester and Birmingham. So bravo to them for reviving this, bravo to everyone involved to bring it to fruition despite its challenges and, why not, bravo to all us who listened to it.