The Rape of Lucretia

Grimeborn, Arcola Theatre, 1st August 2018

The Rape of Lucretia is a story with a long historical and artistic pedigree. It lies at the heart of the creation legend of the founding of the Roman Republic in the late 500s BCE, was documented by Livy and Ovid, then St Augustine, appears in Dante, Chaucer and Lydgate, was the subject of a poem by Shakespeare, (and Lucretia was referenced in some of his plays), and was a staple of much Renaissance and later art, notably works by Titian, Veronese, Rembrandt, Dürer, Raphael, Botticelli, old Cranach and Artemisia Gentileschi. The worst of these, depicting the rape, are violently voyeuristic, the best examine Lucretia’s subsequent suicide whilst avoiding gory titillation. Check out Rembrandt’s two takes on the latter, (see one above), Veronese’s and, best of all, Artemisia Gentileschi’s.

The story has undergone a few variations through the ages but, in the events of the Britten opera here, essentially runs like this. Tarquinius, the son of the last king of Rome Tarquinius Superbus, is sent on a military errand where he meets up with Collatinus and Junius. They have a few beers, (or the Roman equivalent), and get to discussing the chastity of the women of Rome. Junius goads Tarquinius into testing the virtue of Collatinus’s faithful wife Lucretia. Tarquinius rides to Collatinus’s house that night and the servants are obliged to let him in. He rapes Lucretia and leaves. Collatinus returns. He comforts her but she cannot bear the shame and commits suicide. Junius tries to atone for his involvement by sparking a rebellion against the King.

As you can see there are multiple perspectives for the creatives who take on this ugly story, and specifically this opera, to alight on. Ronald Duncan’s libretto, which in turn is based on the French play Le Viol de Lucrece by Andre Obey, uses the device of a Male and Female Chorus to frame the action and, incongruously to me, to tack on a Christian message, notably in the Epilogue, to the “pagan” tale. He also uses some pretty high-falutin’ and fancy language for both chorus and in the dialogue. It is easy to grasp what is going on but the florid text does sometimes get in the way a bit.

Fortunately though the genius of Mr Benjamin Britten is at hand. The Rape of Lucretia, like Albert Herring and The Turn of the Screw which we recently saw in the superb production at the Open Air Theatre (The Turn of the Screw at the Open Air Theatre review *****), is a chamber opera scored for just thirteen instruments. As usual it took me 15 minutes or so to adjust to BB’s astounding mix of tonality, effect and experimentation but, once the ears were fully up and running, this music was as dazzling as I remembered. It has been a fair few years since the last performance I saw, (can’t actually remember where), and I can’t say it is a turntable regular Chez Tourist, but, no matter, I was mesmerised. The Orpheus Sinfonia under Music Director Peter Selwyn, (who provided piano recitative accompaniment), were well up to the task and it was thrilling to hear the score in such an intimate space. The Sinfonia was founded to give an opportunity for talented young musicians to pursue a career that, trust me, they are doing for love not money. On this showing there are some fine talents here.

How then to deal today with what is plainly a deeply unsettling story? Britten was drawn to it as yet another “corruption of innocence” parable, the theme of so many of his operas. Yet I am not convinced that, as with those other operas, he fully thought through the perils of the material he was dealing with. Director Julia Burbach though made the most of the “universal” message that Duncan and Britten devised. The modern dress Male and Female Chorus, (here tenor Nick Pritchard and soprano Natasha Jouhl), open the opera by explaining how Rome under the Etruscan King Tarquinius Superbus is fighting off the Greeks and how the city has fallen into depravity. A Christian message for sure but as, subsequently, the two singers voice the thoughts of the male and female protagonists and move the story on, “out of time” as in classical Greek tragedy, a device to “explain” the motives and psychology of the characters and to involve us, the audience, in the action.

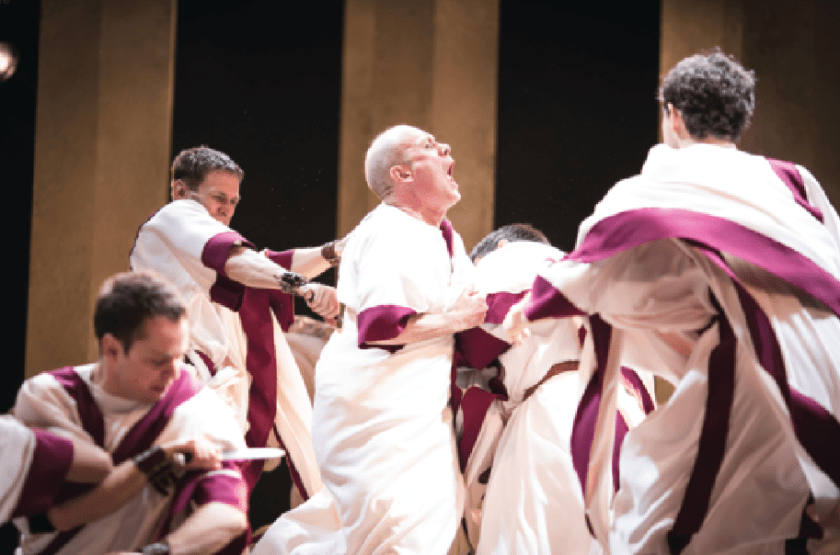

Fealty to Duncan’s libretto maybe means the production cannot resonant quite as volubly as it might have wanted to current MeToo awareness. Even so the drunken toxic masculinity, the fear that grips Lucretia and her two servants on Tarquinius’s arrival, the rape itself and Lucretia, broken, arranging flowers the next morning, are immensely powerful scenes reflecting the music, the acting and the movement of the characters and chorus under Julia Burbach’s direction. Having the Male and Female Chorus move through, and even at some points shape, the action was a smart move which offered insight.

I am not sure that any of this made the content of the story more palatable though and I can certainly understand why some may think this is an opera better left unstaged. I would suggest you see a production and decide for yourself though. This is not the only misogynistic opera: far from it. But when Lucretia, as here, is literally staring directly at you after the violence she suffers, it is impossible to ignore. And, when she dismisses Collatinus’s plea that Tarquinius’s action can be “forgotten”, the reason for her suicide is shifted from shame to anger.

The performances were uniformly excellent, particularly the two Chorus and contralto Bethan Langford as Lucretia. Bass Andrew Tipple was a deliberately vapid Collatinus, James Corrigan was a suitably odious Junius and a menacing Benjamin Lewis skilfully conveyed Tarquinius’s sickening importuning ahead of the rape. Claire Swale and Katherine Taylor-Jones both sang beautifully as Lucia and Bianca, Lucretia’s maid and nurse respectively. I am guessing that the performers had to take it down a notch or two in the Arcola space but what was lost in singing power was more than made up in clarity and immediacy.

The opera was staged as part of the Arcola’s Grimeborn festival which is not into its 11th year with 55 performances across 17 productions. For those of us who cannot face, or afford, the trip to Glyndebourne, where this opera was premiered in 1946, Grimeborn offers a bloody marvellous alternative. The small space means poncey C19 boring opera is off the agenda or the creative teams have to aggressively rethink it. New interpretations and new work abound. Chamber opera is in its element. Everything comes alive and acting, not vocal histrionics or regie-directorial setting, takes centre stage. All for around 20 quid a pop or less if you arm yourself with an Arcola Passport which is simply the second best gift to culture on the planet, after the Arcola AD Mehmet Ergen who should be knighted this minute.