Sweat

Donmar Warehouse, 24th January 2019

Who is the greatest living playwright (in the English language). Caryl Churchill. Obviously. Who is, in the opinion of the Tourist, probably the most talented playwright under 40 in Britain today. Ella Hickson. What was the best original play the Tourist saw last year. John by Annie Baker. And the best play so far this year. Sweat by Lynn Nottage.

So far this year the Tourist has seen 19 plays (well 18 and a half to be exact of which more in a future post. Actually it is quite a bit more than that but I have condensed the Pinter at Pinter season ). Too many. Certainly but such is the life of the friendless, privileged layabout.

Only 4 by women though. Not good enough. Either by me or the industry. Last year, (I shall refrain from the total number – it is embarrassing), just 25% of the plays of the plays I saw were by women. If I take just new plays (not classics or revivals) the ratio edges towards 40%. Not great but getting better.

Before I get started I note that Sweat is transferring to the Gielgud Theatre from 7th June for 6 weeks or so. If you haven’t seen it don’t hesitate.

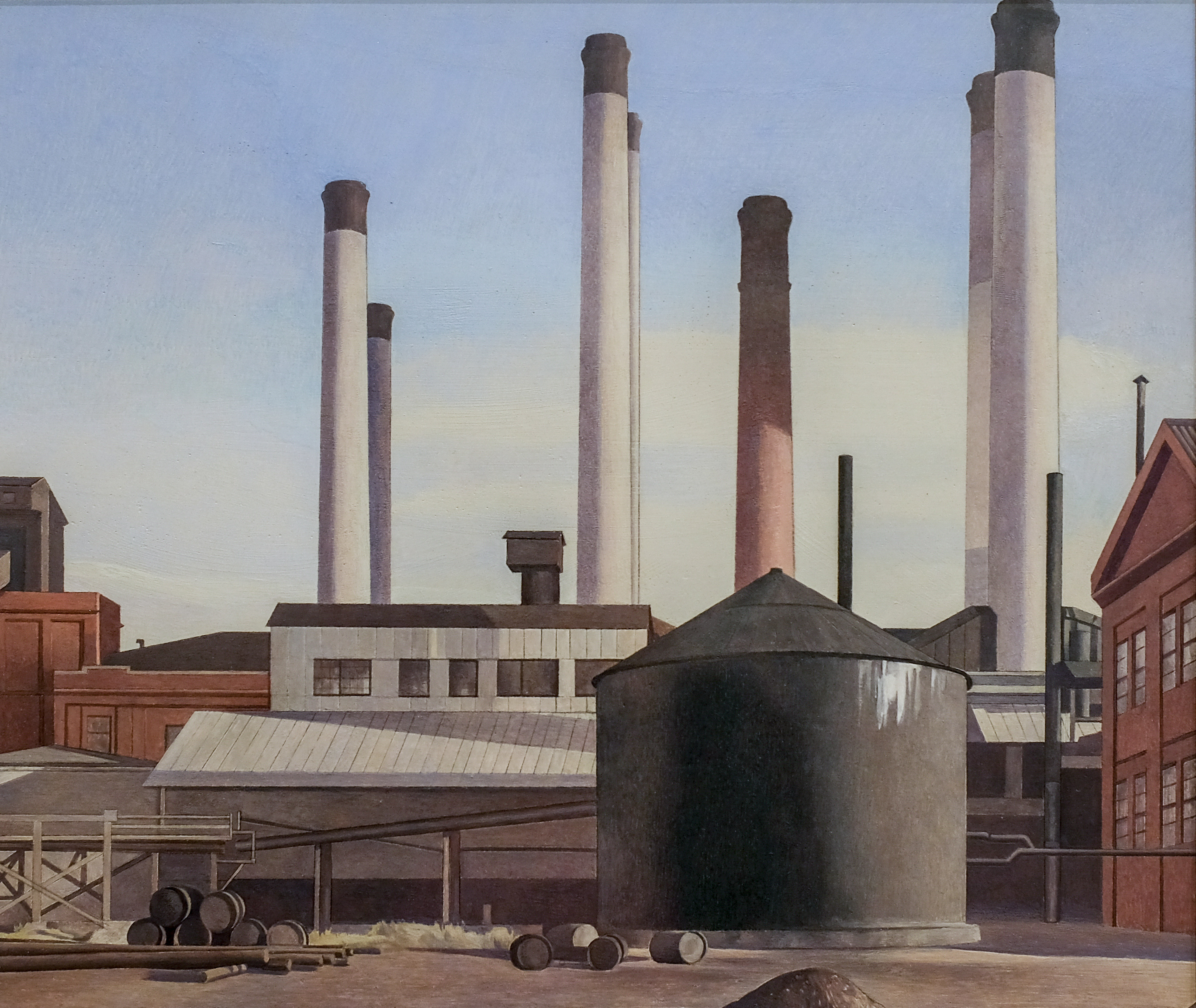

Sweat is set largely in a bar in a de-industrialising town in the rust belt of the American North East. Lynn Nottage and her team spent over two years interviewing residents of Reading, Pennsylvania in preparation for writing the play. Now, as I know from having seen another Pulitzer Prize winning entertainment, Julia Wolfe’s oratorio Anthracite Fields, Reading was, in its heyday through the second half of the C19 and first few decades of the C20, a powerhouse of US industry built on iron and then steel, its proximity to coalfields and on the railway. Its fall was precipitous however and it became, by the time of the 2011 census, one of the poorest cities in the entire country, though it is now being reinvented as a centre for cycling nationally.

Ms Nottage’s play is set in 2000, though it begins in 2008, with the release of Jason (Patrick Gibson) from prison into the hands of probation officer Evan (Sule Rimi who has, thankfully, popped up on numerous occasions for my viewing pleasure). Jason is “reunited” with once friend Chris (Osy Ikhile). Neither is in a good place. We then flash back to see how we got to that place. Jason’s mum Cynthia (Claire Perkins), Chris’s mum Tracey (Martha Plimpton) and Jessie (Leanne Best) are celebrating in the bar managed by Stan (Stuart McQuarrie) and where Hispanic-American Oscar (Sebastian Viveros) is employed. Cynthia is estranged from husband Brucie (Wil Johnson) who has spiralled downwards after being shut out from the factory during a strike some years ago. All three, tough, women are also employed at the local steel-works, as are the boys, (though Chris wants another life), and as was Stan until an industrial accident, and it is against this back-drop that the story unfolds.

Now you might be thinking, uh-oh, this is going to be one of those terribly worthy political plays where a finger-pointing, hand-wringing lesson about economic and social injustice sucks the life out of the drama and leaves you with conscience enhanced but ever so slightly bored. Well nothing could be further from the truth. The relationships between the characters, and the extraordinary, often moving, dialogue, that describes them is perfectly pitched. The play is flawlessly plotted, structured and executed. The fact that Lynn Nottage is able to locate this within a broader economic and social context (blimey, she even nails the mixed blessings of NAFTA), to conjure up time and place (and history) and to explore fault-lines along racial, class and gender divides, without getting in the way of the personal drama, is what makes this such a complete work of theatre. This is fiction, with no trace of verbatim, but the process of its creation, the people that Ms Nottage talked too, make it very real.

There is nothing redemptive or uplifting here but that is the reality of the damage that the economic dislocation and industrial change has brought to the region and by implication, those left behind in the US and across the Western world. The play opened in New York in 2016 just before Trump’s election. It could not be more relevant. The shattering of the American Dream is hardly a novel subject for drama but Sweat brings home the causes and consequences of the shift away from heavy industry and manufacturing, from managed capitalism, through financial capitalism into the information age. Ms Nottage has said that “we are a nation that has lost our narrative”, which sums up the disillusionment, rage and frustration which is now being vented by those that have lost out and, for whom, the dignity of labour has been upended and faith shattered in a system which was supposed to protect them. Setting the play in an all-American bar, rather than the workplace itself, is a masterstroke, for this is an arena in which the tensions can truly erupt.

Even a play this perfect still needs cast and creatives to deliver. Indeed any flaw in delivery would probably be more visible. Fortunately we are in the secure hands of director Lynette Linton, assistant at the Donmar and now in the hot seat at the Bush. Frankie Bradshaw’s set is wonderful as the bar descends, altar-like, inside a framework of steel girders, supported by Oliver Fenwick’s lighting design and George Dennis’s sound. The cast is uniformly exemplary, another triumph for dialect coach Charmian Hoare, (though this Brit is no expert), with Claire Perkins particularly excellent as the striving Cynthia and Martha Plimpton just, and for once the vernacular is justified, awesome.

Best of all Lynn Nottage didn’t just helicopter in to extract her story and then move on (as it happens now to a work around the life of Michael Jackson – crikey!). No, she and the team, went back to show the play and to engage in many ways with the community across multiple projects. Drama matters. The Greeks knew that. Hard to see how it could matter more than with Sweat.