The Starry Messenger

Wyndham’s Theatre, 5th August 2019

The Tourist, despite his evident theatre addiction, rarely jumps in to secure a ticket early for the “star” vehicles that crop up in the West End. It usually pays to wait to see how well regarded play and production are. Demand often adjusts to supply, pushing down price, in a pleasingly classical economics way. So far this year the strategy has worked for True West, The Price, Rosmersholm, Bitter Wheat and this, The Starry Messenger. I enjoyed Kenneth Lonergan’s last film Manchester by the Sea and see he had a hand in the writing of Scorsese’s The Gangs of New York, though plainly that film’s sprawling genius largely stems from Daniel Day-Lewis’s turn as Bill the Butcher. The reviews of A Starry Messenger from its original off-Broadway production in 2009 were also largely promising, (though it apparently got off to a very shaky start).

Matthew Broderick had a small part in MBTS and in Mr Lonergan’s epic failure Margaret, and larger roles in a whole string of Hollywood pap that has passed me by. However, he is probably still most famous for his early turn in cult teen movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which is, IMHO, a bloody awful film, and, for the Tourist, in Alexander Payne’s Election, which is certainly not. And maybe also for being married to Sarah Jessica Parker, a terrible actor, though maybe that is the fault of the execrable Sex and the City in which she “starred”. And for a tragic traffic accident for which he seems to have escaped punishment. (The Tourist takes a dim view of the scale of justice usually meted out in such circumstances).

His co-star here was Elizabeth McGovern. Another Hollywood stalwart that the Tourist barely recognises. And this despite her living in Blighty and treading the boards in London in recent years. You will no doubt know her best as someone called Cora, the Countess of Grantham, in Downton Abbey. Of which I can truthfully, and proudly, say, I have only seen for maybe ten minutes in total, and that by accident. This is what comes of being an intellectual snob, devoting one’s cultural energies to quality British TV drama, art-house cinema from around the world, and elevating the theatre above all other performing arts.

Mr Broderick plays the stoical Mark Williams, a public lecturer in astronomy, at the Hayden Planetarium in New York. Ms McGovern is his chipper schoolteacher wife Anne. They have one, unseen though not unheard, teenage son. Mark is middle-aged, not quite in crisis, but a bemused, and amused, pedant whose life is passing him by. He still loves Anne but gentle bickering is their default mode of exchange. When animated, Puerto Rican, single Mom, nurse, Angela Vasquez stumbles into his lecture hall though, something of his life force returns. They have an unlikely affair. Tragedy strikes. So far so predictable. What makes all this cliche forgivable is Mr Lonergan’s ear for dialogue. These are ordinary people, doing ordinary things, in their ordinary lives, but with a depth of feeling which reaches for the infinite. They talk but don’t really listen. Misunderstanding and frustration abounds. At least that’s the idea. Hammered home with all the stargazey, metaphorical opportunity afforded by Mr Williams’s employ, especially right at the end. Faith plainly is not the answer in KL’s book.

It goes on a bit, nearly three hours, and, whilst I can remember the basics of the plot, and, Chiara Stevenson’s elegant set, with its night sky backdrop, the detail is already fading. It is fortunate that Matthew Broderick is playing a relatively dull man. Otherwise I might have mistaken him for a relatively bad actor. As it turns out, and particularly in the more humorous passages, his performance actually works. He is a modest man and, though, to paraphrase Churchill, he has much to be modest about, he is still striving for a good life.

Ms McGovern is an altogether more convincing stage presence but sadly we see too little of her and her part is underwritten. Rosalind Eleazar as Anela sails convincingly through the more hackneyed of her character’s traits, whether in the awkward and anguished scenes with Mark in her apartment, or in those with the terminally ill Norman (Jim Norton), the crusty old boy in her care, and his tetchy daughter Doris (Sinead Matthews), which provides the sub-plot. There are are regular laughs, often extracted from the regular members of the class Mark teaches, notably the some way behind the curve Mrs Pysner (Jenny Galloway), and from the wonderfully tactless, serial course-attender Ian (Sid Sagar). (I see that Kieran Culkin, another relater KL collaborator, played Ian in the original Broadway production. If you haven’t yet seen his turn as Roman Roy in HBO’s Succession then you are in for a treat). Another highlight is Mark’s conversations with his more successful, though still supportive as he pits Mark forward for a research role, academic colleague Arnold (Joplin Sibtain).

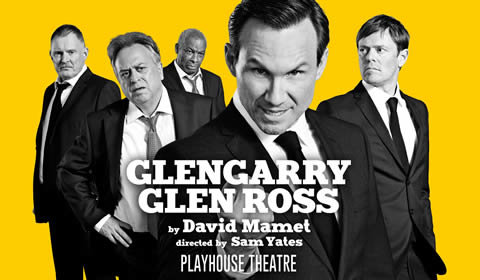

Chekhov it ain’t. But sometimes, in its wriggling ambivalence, it does a fair impression. KL, as you will probably have surmised, has spent far more time on the detail of the lines than the novelty of the plot or the wider context. But somehow, despite the irritations, I sort of quite liked it. Sam Yates last outing was with Ella Road’s excellent debut play The Phlebotomist but prior to that he, as here, rose to the occasion to direct acting royalty (notably Christian Slater) in the excellent Glengarry Glen Ross revival.

The original Hayden Planetarium, as we see at the end of the play, closed in 1997, to be reborn as Rose Centre foe Earth and Space attached to the American Museum of Natural History, (which I know from bitter experience feels almost as large as the universe itself). As he reveals in the programme he and Matthew Broderick went their together when they were kids. So now I understand why he has been so generous to his lifelong friend. After all, in the end, friends and relationships are all we really have.